Concept attainment : a case study comparing a child profiled... grade classmates

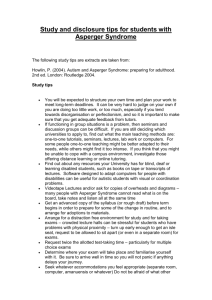

advertisement