Document 13536149

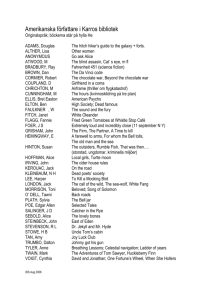

advertisement