State of New Jersey

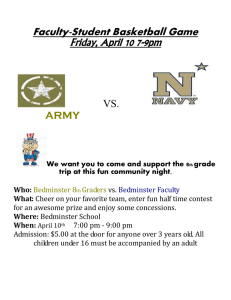

advertisement