An Evaluation of Local Laws Requiring Government Contractors to Adopt Non-Discrimination and

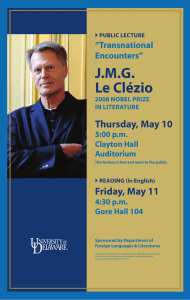

advertisement