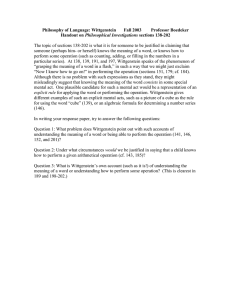

Tractatus Wittgenstein’s Later Criticism of the James

advertisement