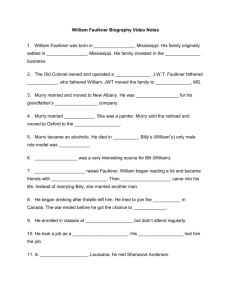

Fear and desire : miscegenation in the postbellum South

advertisement