Direct and correlated responses to selection for reproductive rate in... by Susan Gail Schoenian

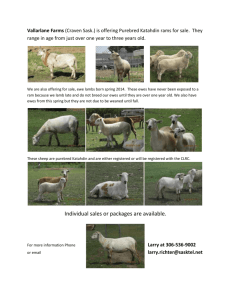

advertisement