Influence of energy or protein supplementation on forage intake of... winter range

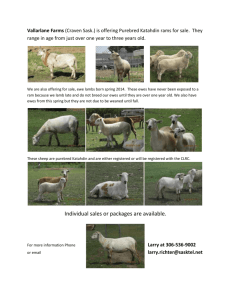

advertisement