Document 13513396

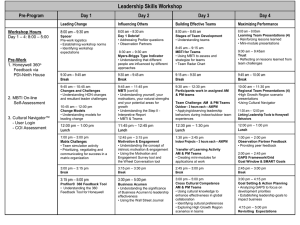

advertisement