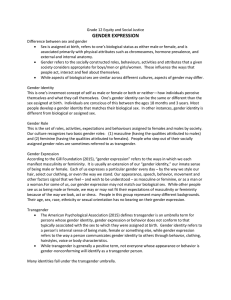

Articles Documenting Gender Introduction

advertisement