Lincoln University Digital Thesis

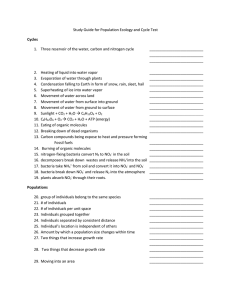

advertisement