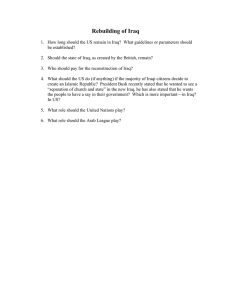

IRAQ

advertisement