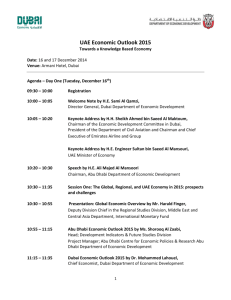

UNITED ARAB EMIRATES

advertisement