Social support and pregnancy outcome by Helen Colleen Stephens Newman

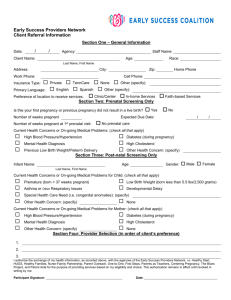

advertisement