A study of the current status of home economics consumer... programs in the United States and specifically Montana

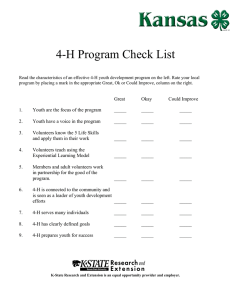

advertisement