The social and emotional needs of the geriatric patient in... by Karen Teresa Ward

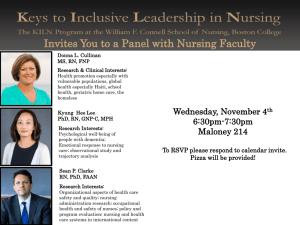

advertisement