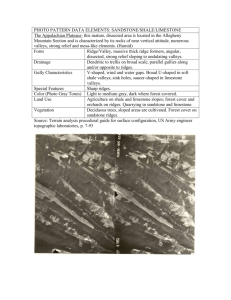

Geology of the Southwestern Horseshoe Hills area, Gallatin County, Montana

advertisement