Histological studies on wool follicles by Mushtaq Ahmad Khan

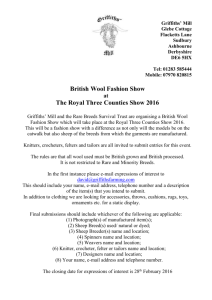

advertisement