Factors contributing to emergency department utilization in a rural Indian... by Cheryl Magee

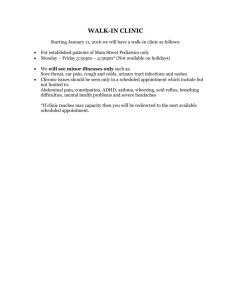

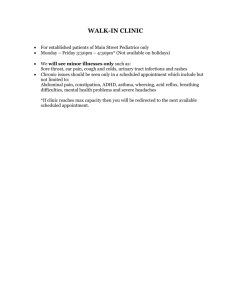

advertisement