A GUIDE TO ESSAY WRITING

advertisement

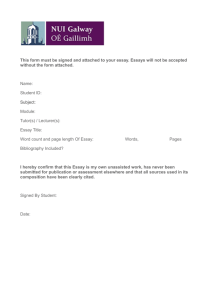

1 A GUIDE TO ESSAY WRITING As a student following a degree programme involving the study of Italian you will have a variety of ways of expressing yourself during the four years of study. These include: writing in Italian on a variety of topics and in a variety of forms and registers; conversation in Italian including short presentations on a variety of topics; seminar contributions in both Italian and English in the form of personal presentations and interventions; and essay writing, both assessed (including examination essays) and 'non-assessed'. In an assessed essay, the mark is determined by two markers and contributes to your overall mark for the module. A 'non-assessed' essay is marked by the tutor for the module and its mark does not contribute to your overall mark for the module. This booklet is about essay writing in English for literature and culture modules taken in the Italian Department. All the recommendations made are valid equally for assessed and 'non-assessed' essays, except where specifically indicated. Examination essays, commentaries and dissertations are discussed in separate sections (sections 17–19). The writing of an essay provides an opportunity for you to communicate your ideas in an ordered and engaging way. There is no one way in which to write an essay. Writing, whether a story, poem or essay, is an intensely personal experience and there are probably as many ways of writing essays as there are people who write them. It is for you to decide how best to combine thinking, reading, note-taking, and writing in order to produce an essay which successfully communicates your understanding of a topic. The more you work on essay writing the greater will be your understanding of your own mental processes, and such knowledge will stand you in good stead for the rest of your life. 1. Choosing the topic Usually you will be given a list of questions from which to choose. Although there are opportunities for specialization through choosing topics that are interrelated (for instance, you may find topics concerning imagery on essay lists for more than one module) it is a good idea to show some spread of interest over your degree work. If none of the suggested topics appeals to you, it is usually possible to negotiate a title with your tutor; in some modules you will be actively encouraged to think out a title for yourself. Some recommendations for choosing a topic: Choose a topic which you find personally interesting, one to which you feel willing to devote some time and energy. Choose the title of your essay early, giving yourself chance to think about it broadly before starting intensive research. Make sure you have understood what the question or topic requires before settling down to work on it. If you are in doubt, discuss the question with your tutor. Think hard about the terms of the question itself: what sort of information and what sort of approach does the question seek; and are the terms of the question straightforward, or are they themselves open to question? 2 2. Reading Your reading will usually be divided into primary texts and secondary (or contextual or critical) texts. i. The primary text is the work (or group of works) on which the question is based. In the following question on Dante there is no doubt what the primary text is: ‘What part does suspense play in the narrative of the Comedy?’ You need a good knowledge of the Divina Commedia to answer this. But in the following question you need to choose your own primary texts: ‘Consider the presentation and function of landscape in the short story’. Much of the success of the essay will depend on the choice of stories (and the rubric to the essay title list will tell you how many you need to choose). It is often a good idea to choose texts from which you can create contrast in your essay: here, texts which allow you to show how different authors (or the same author) use landscape in varying ways, and to discuss whether, despite their differences, there are some convergences. It is advisable to gain a thorough and personal knowledge of the text(s) in question before exploring contextual reading. This is particularly the case when the question is asking for a detailed reading of, say, a poem or short story. As you will be reading the text in Italian this stage may take longer and a higher proportion of your time than it would for an English literature essay. Third and fourth year work in the Dante and Italian Renaissance Literature modules will include quite a long time exploring the text and using the edition’s footnotes to explain words and concepts that are new to you. ii. Secondary (or contextual or critical) material can be divided into various kinds. If you are working on short fiction you may want to know more about the literature of the period you are working on, as well as narrative strategies and the writer. An essay on a text of the Italian Renaissance may require historical and political knowledge, further exploration of philosophical ideas popular at the time and current literary approaches. You may decide that you want to approach the topic within a particular conceptual framework (e.g. psychoanalytic, feminist, deconstructionist) which requires specific reading. In work on literary texts you will also find in most cases a wealth of scholarly engagement with the text itself. Clearly you cannot read it all and you will have to be selective. Your essay is not meant to be the last word on, for instance, imagery in Petrarch’s Canzoniere - indeed it is important to remember that there is no ‘last word’, for all criticism is part of a process, a dialogue. Seek out secondary material which concentrates on the topic which concerns you: if you need help identifying this, or feel overwhelmed by the amount of material available, discuss with your tutor the most appropriate texts to consult. Avoid the tendency to think that because a view is in print it is ‘right’ or ‘the final word’. Remember that what counts most is YOUR views on the text, argued clearly and coherently. Some of what you read will quite properly alter what you think about a text, will give you new insight and sharpen your perception. But all criticism needs to be read judiciously, with critical awareness. It is good to set your views within the context of critical writing on the subject (particularly in final year 3 essays), but never let your perceptions be swamped by your critical reading. Aim to synthesize the various critical approaches to the topic or text in a way which leads you to a clear expression of your own interpretation of it. Like anyone else, scholars are prone to use some arguments that are stronger than others, and the views or research of some scholars are more dependable than others. If you are dealing with a book and are unsure to what extent its arguments are accepted or eccentric, it will be useful to read a couple book reviews on it. Some of the contextual reading you will find on reading lists that accompany the module, or will learn about from discussion with your tutor; you will also probably find other books and articles for yourself from using CD-ROM facilities or electronic databases (see section 3 below). Be flexible: contextual or primary reading for one module may well relate to another: e.g. theoretical approaches to fiction learnt in Short Fiction and the European Novel can be relevant to other narrative texts (e.g. on the Experiments in Narrative module or on Dante); notions of the state gained in International Studies modules can relate to your study of Machiavelli in Renaissance Rivalries; study of cinematic techniques in Textual Readings will inform your interpretation of films included in Representations of Modern Italy or Experiments in Narrative. The way one critic reads a poem may well provide a fruitful method for reading a poem by another poet, and one film director's representation of a historical period may serve as an illuminating contrast with a novelist's account of it. Modules are not rigid, self-contained units of study, but rather, as the name suggests, they should be interlocked to assemble a complex and flexible understanding of a broad subject - in this case, Italian language, culture and society. Ideas or knowledge acquired in one module will often cast interesting light on another, and you should cultivate this sort of interactive approach. 3. Resources Obviously the texts you own and the books and periodicals in the library will be your major resources. Sometimes a book you want to consult may not be available in the library because someone else has checked the volume out. In this case, you may use the ‘request’ function at the top of the library record for that book. If, however, the library does not have the book or periodical in its collection, go and see your module tutor or personal tutor. It is sometimes possible to get the text for you on the interlibrary loan system (i.e. borrow it from another library) and sometimes your tutor has a copy which s/he is willing to lend. Individual bibliographies for specific modules will give you details of articles in periodicals but you may like to explore further for yourself. Take a look at the recent issues of periodicals in the shelves on the ground floor (earlier numbers are kept on the third floor across the bridge in the library extension). Some useful titles are: Rassegna della letteratura italiana, Giornale storico della letteratura italiana, Italian Studies, Forum Italicum, The Italianist, Italica, Modern Language Notes (there is an Italian issue each year), Journal of the Warburg & Courtauld Institutes, Studi sul Boccaccio, Renaissance Quarterly, Renaissance Studies, The Yearbook of the Society for Pirandello Studies, The Journal of the Romance Institute, The Modern Language Review, Lettere italiane. Use the library website to help you locate books in the library. You can also use 4 various CD-ROMs to locate criticism available on your author or topic. There is a very useful CD-ROM for Italianists called LIZ (Letteratura Italiana Zanichelli). This will concordance for you; e.g., it will tell you how many times and where the word ‘savio’ occurs in Boccaccio’s Decameron or how often Petrarch used the phrase ‘la fera bella’. If you need help in using this resource, ask a librarian or a tutor. William Pine-Coffin is the librarian responsible for Italian and is always very willing to help students of Italian to make the most of the library's resources. You should also be aware of electronic databases that are available through the library website. JSTOR gives you full-text access to various articles and book reviews, but remember that (i) it does not include chapters in books, (ii) there is a lag-time of several years between an article’s publication and its appearance in JSTOR, and (iii) JSTOR tends to focus on journals of general scholarly interest rather than on journals devoted to specific fields (for instance, Italian Studies, Giornale storico della letteratura italiana, and Studi sul Boccaccio are not included, but Renaissance Quarterly is). From the library’s home page, you may click on ‘Resources’, which will direct you to ‘Print and electronic resources’. If you then specify, under ‘Subject’, ‘Italian’ (or ‘French’ or ‘English’ or ‘Renaissance Studies’ ...) you will be taken to a number of other useful resources. 4. Note-taking You will need to take notes while you are reading both primary and secondary texts. These notes serve as i) a bank of information or opinion derived from the texts you have read; ii) a collection of raw materials from which to assemble your own interpretation of the texts or topic, i.e. an essay; iii) a set of references to be discussed or quoted in your essay. Here are some recommendations for making your note-taking as efficient as possible: Do not allow note-taking to be a substitute for genuine reading and interpretation of the text. Your notes should consist of your own coherent summaries of and comments on the material you are reading, rather than isolated passages copied from the text, which do not necessarily make sense to you on re-reading. Only copy quotations where you think they articulate an argument succinctly and therefore will provide a useful discussion point in your essay. It is very important to know where you have taken a quotation from, or where you have come across a certain idea, so you must reference your notes. Head your notes with the full bibliographical details (see below) of the book or article you are reading and put at least an abbreviated reference on every sheet of paper you use. When copying a quotation for use in your essay, always put the passage in quotation marks and note the page reference at the end of the passage, so that you have it to hand when you write the essay. In case you should later abbreviate the quotation, indicate in your notes if the quotation spreads over two pages. This can be done with a double slash or some personal marker of your own: e.g. ‘The second general achievement of the humanists was historical. Besides reviving a specific ethical tradition and enhancing knowledge of antiquity, they perceived that antiquity was a lost civilisation. This insight itself produced their attainments in moral philosophy and classical scholarship. Because they saw that a 5 lost world had spawned ancient // literature, they grasped that antiquity possessed distinctive and finite forms' (pp.xiv-xv). [Your notes will have been headed: John Stephens, The Italian Renaissance: The Origins of Intellectual and Artistic Change Before the Reformation (London and New York: Longman, 1990).] Be absolutely clear in your notes about what is your own opinion and what is paraphrased or summarized from the text. Use some indication to differentiate your own comments from summaries and quotations, e.g. underline in a different colour, use square brackets plus the words ‘my comment’ or ‘me’. If this distinction is not carefully maintained in your notes, you run the risk of the resulting essay being penalized for plagiarism (see section 7 below). 5. Organizing your essay It is essential that your essay moves forward with a logical and coherent argument, rather than being a collection of random paragraphs. What you use in the essay - i.e. the core information - is clearly a crucial component of it, but a substantial proportion of your mark will also be determined by how you use and present that information (see departmental assessment criteria in section 15). In order to produce a well-organized essay, you will need to make a plan. There are various organizing principles. You can progress from the simple to the complex, beginning the essay by giving the overall picture and then going into greater detail. You can construct a debate within your essays by rehearsing the arguments on one side of the case in the first part of the essay and then on the other side in the second part; or by discussing the pros and cons of each argument in turn. The principle you use should be determined by your own interpretation of the topic: ask yourself, 'What am I aiming to convey to my reader?' This in turn may well be determined by the essay question: an essay which responds directly, but also sensitively and with flexibility, to the question asked is usually a successful one (provided, of course, the response is supported by sound understanding of the materials). Some recommendations follow: DO answer the question. To discuss the terms of the question or to cast doubt on an opinion expressed is often a sophisticated and successful tactic, but DO NOT hijack the question and divert it towards a topic you would prefer to write on. DO make sure your essay has an introduction and conclusion. The introduction should lead the reader into the argument, but should not be so broad as to be banal. The conclusion should sum up your argument but should not repeat it. DO NOT recycle your introduction as your conclusion. DO use the conclusion to drive home your own, individual opinion at the culmination of this research and writing exercise. In comparative essays, DO NOT write two discrete essays which you then stitch together in your conclusion. Also, DO NOT distort one text to make it fit in with an overall theory. Convey the individuality of each text, but draw out points of comparison and contrast and discuss them with regard to both or all texts together. DO NOT re-tell the story of a novel or summarize a plot in your essay. You can assume that your reader knows the text well. DO be clear about the place within 6 the context of the whole work of any incident or character you are discussing, but make this ancillary to the opinion you are expressing of that incident or character. DO NOT include in your essay biographical detail about writers or directors, or historical detail about the period, or critical detail about the literary or cinematic genre, except where it contributes directly to the formulation of your argument. Your essay is a piece of critical analysis, NOT a narrative. DO engage your reader and express your own personality in your writing. Your essay should present convincingly some sound critical research - it is not an exercise in creative writing or an advertising spot -, so DO NOT use a style which is excessively florid or flippant, but DO try to invite your reader to share your individual perspective on the topic. DO express your own position with regard to the question or topic clearly, but DO NOT express personal opinions which are vague or ungrounded, such as 'I think Natalia Ginzburg is an important twentieth-century Italian woman writer'. The word 'important' here is meaningless, unless you have explained in exactly what ways you believe her activity to be important. DO NOT allow your essay to become a list of points; i.e. avoid beginning each paragraph with phrases such as, 'Another example of animal imagery in the Inferno is...', or 'The next scene in which we see the brothers fighting takes place after...'. Some essay questions may lead you towards this sort of approach by asking, for example, how an author progressively builds a theme or character, so beware. 6. Use of secondary sources There are various ways in which you can use your secondary and contextual reading in your essay. The following provides examples of some of these ways: i) You can quote directly from another text either to support your argument or to provide a context for what you want to say: e.g. As Valerie Shaw has said, ‘if a short story’s aim is to achieve a single concentrated impression, then it must move swiftly; it cannot linger to unfold for the reader the little incidentals and wayward episodes, the dull patches and uneventful intervals through which he [sic] actually experiences time’ (Shaw, p.46). Edgar Allan Poe’s stories are excellent examples of this narrative mode. In....... [Sic in square brackets (it means ‘thus’ in Latin) here indicates to the reader that you would have put ‘s/he’ or ‘he or she’. It is used to indicate that the writer you are quoting has written something incorrectly, idiosyncratically, or in a way which you disagree with.] ii) The same idea can also be expressed with a short direct quotation and free paraphrase (or if you prefer, full paraphrase): e.g. A number of writers see the aim of the short story as one of providing a ‘single concentrated impression’. If this is the case then the narration must eliminate idiosyncratic detail and minor incident, it cannot reflect those long periods of time when nothing seems to happen but which contribute to the reader’s experience of time (Shaw, p.46). Edgar Allan Poe’s stories are excellent examples of this narrative mode. 7 In... iii) You can quote because you want to take issue with what the writer says. e.g. François Wahl identifies the same feeling, and offers a specific explanation: 'PVT [sic] possedeva una conoscenza - un’esperienza - senza pari della cultura “marginale”, cioè di costumi, musica e testi, che gli permise di fissarne per sempre la voce. Questa cultura, però, mai riconosciuta come propria da PVT, scomparve dai suoi ultimi libri' (Panta 9, p.253). Wahl is mistaken, I think, in suggesting that marginal culture abandoned the writer in his later works. iv) You may wish to refer to a number of sources in order to recount the history of, for example, an idea of literary form, or to establish your own position. In this case it is often a good idea to paraphrase the argument of each critic rather than quoting them individually; too much direct quotation can make rather a disjointed essay. e.g. Ammirati feels that the complex structure overreaches itself (p.42); La Porta finds the novel ‘irrimediabilmente fredda’ (p.171; italics in text). Zancani's comments (1993) are most revealing: he starts by describing it as 'a rather complex novel' (p. 232), then... Each critic you paraphrase will need to be acknowledged; see section 8 on Referencing below. v) You can set one critic against another and agree with one - or neither. e.g. Sapegno maintains: 'E’ inutile chiedere al Poliziano una invenzione costruttiva di vasto respiro: occorre invece prendere ciascun episodio a sé: la caccia, l’incontro con Simonetta, il regno di Venere' (p.46). This is a view countered by McNair, however: ‘The description of the Realm of Venus is neither a digression nor an episode, but the central arch of Poliziano’s poetic structure’ (p.40). Contradictory though these statements may appear, it is my view that they articulate different interpretations of a central structural principle in Poliziano's Stanze per la giostra. 7. Plagiarism In all the above instances, whether you are quoting directly, paraphrasing, alluding to a critic’s view, or setting one critic against another, you must cite your source(s). You must also cite your source(s) if your general argument is influenced by what you have read but you are not quoting or paraphrasing. If you do not cite your sources you could be accused of plagiarism. Derived from a Latin word plagarius originally meaning ‘plunderer’ or ‘kidnapper’, plagiarism is the appropriation of ideas and/or passages of text from another work or author. It is trying to pass off as yours what is not yours. In a culture in which authors own copyrights of their works and consider their writing as their property, plagiarism is a form of theft. It is therefore important to get into the habit early on in your degree programme of saying from where you have taken your material. 8 Plagiarism is considered a serious academic offence, and there are penalties for offenders. Procedures are set out in the University Calendar, Regulation 12(B). A copy of the regulations is on the notice board. Penalties can include the award of zero for the piece of work where plagiarism is proved to have taken place and, in some extreme cases, the award of zero for the whole module. 8. Referencing Acknowledging your sources means using a reference system. There are a number of ways of referring to sources and different publishers use different ‘house styles’. All referencing systems have the same objectives. They give credit where it is due by making it clear to the reader who is responsible for the ideas and information in the piece of writing; they allow a reader to check the evidence on which the argument is based; and they facilitate the circulation of knowledge in the scholarly community. (As you will find out for yourself, following up the source of an idea presented in a footnote or reference is one way of discovering further knowledge.) Students of literature are usually advised to use the style set out in the Modern Humanities Research Association guide known as MHRA Style Guide (the 2002 edition is available on-line at www.mhra.org.uk). This guide, which includes a great deal of useful information on mechanics such as use of quotation marks, spellings and punctuation, has two chapters (9 and 10) on the use of footnotes and references. The following is a simplified version of the MHRA guidelines, suitable for essay writing. Note that there are two main systems of referencing, the ‘humanities’ system and the ‘author–date’ system which is especially used in the social sciences. Although both of these are acceptable to the Department of Italian, the ‘humanities’ system is the one mainly used in literary studies, and you should become proficient in using it. Also note that there are possible variations of presentation within each system; you should choose the one that best suits you and stick with it. (The important point is to be consistent) Both systems make use of a bibliography at the end of the essay. This list is not meant to include all the material you may have consulted in preparing your essay (as is usually the practice in Italy), but only what you have actually quoted or referenced. The list should be ordered—alphabetized by author’s surname and by title. It is sometimes advisable to separate the list into two parts, primary texts and secondary texts. a) ‘Humanities’ system of referencing: bibliography. Each list should observe the following guidelines: i) books Boccaccio, Giovanni, Decameron, introduction, comments and notes by Antonio Enzo Quaglio, 2nd ed, 2 vols (Milan: Garzanti, 1980) Carruthers, Mary, The Book of Memory: A Study of Memory in Medieval Culture (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993) Chadwick, H. Munro, and N. Kershaw Chadwick, The Growth of Literature, 3 vols (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1932–40; repr. 1986) 9 Dizionario storico della letteratura italiana, 3rd ed., edited by Luca Bianchi, Nino Pertile, Natalino Sapegno, 4 vols (Turin: UTET, 1988) The Renaissance Philosophy of Man, edited by J. Herman Randall, Jr. and Paul Oskar Kristeller (Chicago: Chicago University Press, 1948) Skinner, Quentin, The Foundations of Modern Political Thought (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1978) ____________, Liberty before Liberalism (Cambrige: Cambridge University Press, 1998) ____________, Machiavelli (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1981) OR: Giovanni Boccaccio, Decameron, introduction, comments and notes by Antonio Enzo Quaglio, 2nd ed, 2 vols (Turin: Einaudi, 1980) Mary Carruthers, The Book of Memory: A Study of Memory in Medieval Culture (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993) OR: Boccaccio, Giovanni. Decameron. Introduction, comments and notes by Antonio Enzo Quaglio. 2nd ed, 2 vols. Turin: Einaudi, 1980. Carruthers, Mary. The Book of Memory: A Study of Memory in Medieval Culture. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993. [Name, title in italics or underlined, place(s) of publication (colon), publisher, date; use of full-stop optional after the author’s name, after the title, or at the end of the entry; an underline means that the author is the same as the last-mentioned; some writers prefer not to invert surname and first name in their bibliographies, but nonetheless their entries are ordered by surname] (ii) chapters in books Branca, Vittore, ‘Ermolao Barbaro e l’umanesimo veneziano’, in Umanesimo europeo e umanesimo veneziano, edited by Vittore Branca (Florence: L. Olschki, 1964), pp. 193–212 Brownlee, Kevin, ‘Dante and the Classical Poets’, in The Cambridge Companion to Dante, edited by Rachel Jacoff (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993), pp.100-119 Kraye, Jill, ‘Moral Philosophy’ in The Cambridge History of Renaissance Philosophy, 10 edited by Charles B. Schmitt, Quentin Skinner, Eckhard Kessler, with the assistance of Jill Kraye (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988), pp. 303–386 Richardson, Brian, ‘Editing Dante’s Commedia, 1472–1629’, in Dante Now, edited by C. Cachey (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1988), pp. 33–132 Scaglione, Aldo and Ugolino Betti, ‘L’età di Aldo Manuzio’, in Dizionario storico della letteratura italiana, edited by Luca Bianchi, Nino Pertile, Natalino Sapegno, 3rd ed, 4 vols (Turin: UTET, 1988) IV, pp. 133–156 [Name of author, title of article within single inverted commas, followed by ‘in’, title of book in italics or underlined, ‘edited by’ + name of editor, place(s) of publication (colon), publisher, date and page numbers preceded by 'pp.'. Variations possible as in [i] above.] (iii) articles in journals Garin, Eugenio, ‘Le traduzioni umanistiche di Aristotele nel secolo XV’, Atti e memorie dell’Accademia fiorentina di scienze morali ‘La Colombaria’, n.s., 16.2 (1947–50), 55–104 Grafton, Anthony, ‘Rethinking the Renaissance’, Journal of the History of Ideas, 53.1 (1987), 333–48 McNair, Philip, ‘The Bed of Venus: Key to Poliziano’s Stanze’, Italian Studies, 25 (1970), 40-48 [Name of author, title of article in single inverted commas, title of journal in italics or underlined, volume number, year of publication in brackets, page numbers without 'pp.' Variations possible as in [i] above] *Note You will have noticed that you use capital letters for the key words (everything except articles, conjunctions, and short prepositions) in the titles of books and articles in English. In Italian, however, you use a capital letter only for the first word of the title (and for any proper names within it). Here are examples of Italian book titles: Giuliana Morandini, La voce che è in lei (Milan: Bompiani, 1980) Antonio Tabucchi, Sostiene Pereira (Milan: Feltrinelli, 1994) – ‘Pereira’ is the name of the protagonist. Some other Italian conventions contradict English ones, e.g. in Italian texts, titles of articles in books or journals are italicized. You should use the English conventions when writing in English. Italian place-names should be given in the English form (‘Milan’, not ‘Milano’; ‘Leghorn’, not ‘Livorno’; ‘Florence’, not ‘Firenze’, etc.) b) ‘Humanities’ system of referencing: footnotes and endnotes. References within the body of your essay to works that you have consulted may take one of two different forms: either in-text references or footnotes. Your tutor may have a preference for one mode of presentation rather than the other, so be sure to ask. 11 In the case of in-text references, you simply indicate your source in brackets, usually at the end of the relevant sentence or paragraph or quotation, for instance, (Boccaccio, Decameron, III, 10, p. 208), (Carruthers, p. 10) or (Carruthers, The Book of Memory, p. 10). In the case of multiple publications by the same author you should always specify which work you are referring to. If you prefer, you can use footnotes (at the bottom of the page) or, less ideally, endnotes (at the end of the essay) for your bibliographical references. Microsoft 'Word' software will do this automatically (select from the toolbar <Insert>, then <Footnote>, and follow the prompts). Footnotes or endnotes can also be used for extra pieces of information or comments that do not quite fit the body of the essay but may be illuminating. However, you should be economical in using footnotes in this way, not allowing the footnoted comments to lead the reader away from your main argument. Note that the format for footnotes and bibliography is not identical: in footnotes it is standard to use the ‘first-name first’ system, to indicate the specific page(s) on which the information referred to may be found, and to close with a full stop. Furthermore, once you have given a full reference in a footnote, later references may be abbreviated: Mary Carruthers, The Book of Memory: A Study of Memory in Medieval Culture (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993), p. 72. [subsequent reference] Carruthers, The Book of Memory, p. 33. Vittore Branca, ‘Ermolao Barbaro e l’umanesimo veneziano’, in Umanesimo europeo e umanesimo veneziano, edited by Vittore Branca (Florence: L. Olschki, 1964), p. 194, note 3. [subsequent reference] Branca, ‘Ermolao Barbaro e l’umanesimo veneziano’, p. 201. Anthony Grafton, ‘Rethinking the Renaissance’, Journal of the History of Ideas, 53.1 (1987), 335–36. [subsequent reference] Grafton, ‘Rethinking the Renaissance’, p. 338. If one reference is exactly the same (including page number) to the one immediately above, you may also replace it with Ibid. (short for the Latin ibidem, meaning ‘in the same place’). But this is a dangerous practice—if you later interpolate a footnote before the Ibid. one, your Ibid. footnote will now refer to a different work. c) The second system of referencing is called citation by the author-date system (sometimes referred to as the Harvard system) and is used by science and social science students. Some humanities subjects are also using it. In this system your bibliography would still be ordered alphabetically by surname and/or title and would look like this: 12 (i) books CARRUTHERS, M. 1993. The Book of Memory (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press) OR: Carruthers, M. 1993. The Book of Memory (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press) OR: Carruthers, Mary (1993). The Book of Memory (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press) [Name – with first name sometimes abbreviated to initial-- date, followed by full stop, title in italics or underlined, place(s) of publication, publisher.] (ii) articles in books BROWNLEE, K. 1993. ‘Dante and the Classical Poets’ in The Cambridge Companion to Dante, edited by Rachel Jacoff (Cambridge, Cambridge University Press), pp.100-119 OR: Brownlee, K. 1993. (etc.) OR Brownlee, Kevin (1993). (etc.) [Name - surname first in caps or lower case (bold optional), date, followed by full stop, title of article within single inverted commas follwed by ‘in’, title of book in italics or underlined, place(s) of publication, publisher and page numbers, preceded by 'pp.'.] (iii) articles in journals McNAIR, Philip, 1970. ‘The Bed of Venus: Key to Poliziano’s Stanze’, Italian Studies, 25, pp. 40-48 OR McNair, P. 1970. (etc.) OR McNair, Philip (1970). (etc.) [Name - surname first in caps or lower case (bold optional), date, followed by full stop, title or article in single inverted commas, title of journal in italics or underlined, volume number, page numbers, preceded by 'pp.'.] If an author has written more than one book or article in one year you differentiate them by the use of small letters of the alphabet (a), (b) after the date. References in the body of the essay are to the surname and date, e.g. (Carruthers 1993, p.10), placed in parenthesis usually at the end of the sentence in which the reference has been made. Footnotes are not usually used with this system, and if they are, only sparingly. 13 When referencing web-sites, the following conventions (based on those of Routledge publishers), should be used: A book, part of book, a journal, or journal article which has been published as such, and is also available on the internet, should contain the usual reference details, followed by the medium (e.g. online), and then the actual electronic address, with the access date in brackets. e.g. Smith, A., Publishing on the Internet (London: Routledge, 1997). Online: http://www.ingress.com/~astanart.pritzker/pritzker.html (4th June 1997). A book, part of book, a journal, or journal article which has only been published on the internet should be referenced as above, but without the place name and publisher. If the reference is to a message on a discussion board, the entry should be: Author (year), ‘Subject of message’, Title of discussion list. Online posting. Available e-mail: e-mail address of list (date). If the reference is to a personal e-mail message, the entry should be: Author (year), ‘Subject of message’. Online. E-mail: e-mail address of author (date). If the reference is to a site which you have consulted, on which the information is not attributed to any individual author/s, the entry should be: Name of organization or company, ‘Title of site’, and of any specific page/s accessed. Online: electronic address (access date). e.g. Università di Roma, La Sapienza, ‘Basili’ (Banca dati sugli Scrittori Immigrati in Lingua Italiana). Online: http://cisadu2.let.uniroma1.it/basili/ (14th September 2000). 9. Quotations When including quotations in your essay, the conventions below should be observed. i) Short quotations (i.e. up to sixty words) should be enclosed in single quotation marks and incorporated in the text of the essay. Quotation or speech within the quotation should be put into double inverted commas to differentiate it from the quotation itself. The full stop of the sentence comes after the quotation. A quotation will usually be followed by the short reference. The full stop should come after the closing parenthesis: e.g. Dante highlights the ironical pathos ‘that lovers who failed to divide in life will never be parted in death’ (Carruthers, p.188). ii) Long quotations (i.e. more than sixty words) should be separated by a line of space from the body of the essay both at the beginning and the end of the quotation. You may indent, if you like and/or use single spacing. You do not use inverted commas when setting out long quotations in this way, and the full stop goes at the end of the quotation, before the parenthesized reference. 14 e.g. The following account of Bauer's first impressions of Rimini is an example: Ragazze seminude che sembravano uscite da Cleopatra o La Regina delle Amazzoni. Altre invece addobbate secondo un look savanico e selvaggio: treccine fra i capelli lunghi e vaporosi, collanine su tutto il corpo, fusciacche stampate a pelle di leopardo o tigre o zebra messi [sic] lì per scoprire apposta un seno o una coscia. Vecchie signore ingioiellate che slumavano avide dai tavolini tutto quel panorama di baldanza e prestanza fisica. (Tondelli, Rimini, p. 40) It is important to ensure that the quotation ‘follows on’, that is, that it fits the syntax of your sentence. You will need to pay special attention to Italian quotations in your English sentence: here the syntax of both languages must harmonize. In the following example, the short quotation from Natalia Ginzburg’s short story ‘La madre’ does not follow on properly: The children’s perspective draws attention to the mother’s untidiness. She would ‘teneva i cassetti in disordine e lasciava tutte le cose in giro’. The quotation does not fit the English syntax because the word ‘would’, implying here habitual action, is already included in the Italian imperfect ‘teneva’ and ‘lasciava’. In this case it would be better to omit ‘she would’ and present the quotation in full: The children’s perspective draws attention to the mother’s untidiness: ‘la madre teneva i cassetti in disordine e lasciava tutte le cose in giro’. Always quote Italian texts in the original language, and, in any language, quote accurately! Quotation from early Italian literature will require special attention as the language will contain forms that are not used today. Points may be deducted for lack of accuracy in quotations, especially when this happens repeatedly, so always doublecheck your quotations. Imprecise quotations give the impression that you care little for the work from which you are quoting and that your analysis may also be untrustworthy. 10. Presentation A well presented essay conveys the impression that you take pride in your work, and suggests that the whole task of producing the essay has been taken seriously. The following paragraphs inform you of current practices that can help you to present your essay well. It is essential at third and fourth year levels, and desirable at first year level, that assessed essays be word processed. There are many good reasons for this: it is easier for the tutor to read work produced in this way; it is easier for you, the writer, to edit and amend your essay once it is written, and so to produce a more concise and streamlined piece of work; it is important that you practice and develop your word processing skills since these are transferable skills which will be highly valued in your career after university. There are, however, dangers in word processing, such as overuse of fancy formatting, different fonts, etc., and the cutting of phrases or sentences 15 resulting in disjointed syntax or logic: be aware of these risks. If you have good reasons for not being able to produce word processed essays, you should see the Chair of the Department of Italian well in advance of the submission date of an assessed essay to see whether you can be granted an exemption. In the case of assessed essays, two copies of the essay should be presented, each with a cover sheet available from the Departmental Office (room 405), and they should be handed by you in person to the Departmental Secretary. (See your year handbook for details of penalties for late submission of assessed essays.) You are asked to produce your work on white A4 paper and to use double spacing. This means that there is space for you to make last minute hand written corrections above the line (which are permissible). Make sure that the type is clear, and check your essay after printing to ensure that there are no unexpected spaces, that the printer cartridge has not run out, etc. 'Non-assessed' essays should be handed in to the tutor for the relevant module, and normally one copy is sufficient. Your tutor will advise you of his/her preferred arrangements for submission of essays. 11. Style Style - your style - is an expression of yourself. Just as choosing clothes is a personal choice, so the presentation of yourself in writing involves personal decisions. Your styles of writing will develop with you, as you work on them. In thinking about how to write your essay, however, you may find it helpful to bear the following in mind. First of all, remember that there are various ways of writing and these tend to be influenced by the purpose of your text, and in particular, who is to read it. The reader may be a real person whom you know well (as, for instance, when you write a letter to a friend), or a body of real people whom you are generally familiar with (such as fellow students if you are writing a review for a student magazine), or a hypothetical group (say, children and 'born-again' children if you were writing the next Harry Potter story). When writing an academic essay, you are in practice writing for one person you know reasonably well - your tutor - and for the second marker for that module, and possibly the external examiner. You should assume that you are writing for an informed academic readership. And you are writing an analytical account. This means that the style will need to be quite formal you should avoid colloquialisms, abbreviations, contractions (such as isn’t or won’t), and appearing familiar in your approach you should aim to be lively and engaging without appearing casual your syntax should be varied and interesting, but not convoluted or difficult above all, be clear: work out your ideas and communicate them as clearly as you can. As with many other of the skills involved in essay-writing and academic work in general, the skill of effective written presentation is one which will be invaluable to you in your life and work beyond university. 16 12. Vocabulary Style can be enhanced by a wide vocabulary. One of the ways to increase your range is to read and listen attentively. Notice words and phrases that appeal to you, and note them down as you read. Where specific terminology is required, use it. As you write, try not to repeat words unnecessarily as this can give the impression of a limp, unadventurous style. Dictionaries and a thesaurus can help here but always try to think of something for yourself first and then use the thesaurus to check that you are right. (Remember that whereas you can use all such aids when writing assessed essays, when you are writing essays in an examination room, there is just you and the paper so you will need to internalize as much as you can.) 13. Grammar, punctuation and spelling i) In the past few years, written English has become less formal than it used to be. Split infinitives (i.e. 'to boldly go', rather than 'to go boldly' or 'boldly to go') are now accepted in a number of instances, as are some colloquial phrases. Nevertheless, in a university essay it is probably best to be cautious and show that you can control formal English without being stilted or pompous. The following will help you to avoid some common mistakes: Make sure that your sentences make sense in isolation, and that they contain a finite verb (a verb limited by person or number), for example: La figlia di Iorio was first performed in Milan at the Teatro Lirico in March of 1904. Directed by Virgilio Talli, Ruggero Ruggeri taking the major role of Aligi. Corrected version: La figlia di Iorio was first performed in Milan at the Teatro Lirico in March of 1904. It was directed by Virgilio Talli and Ruggero Ruggeri took the major role of Aligi. Make sure also that the verb agrees in number with its subject: The author's interest in contemporary politics, and particularly in the marginalization of women in the political arena, come increasingly to the fore in later novels. The singular noun, 'interest', is the subject of the verb. Corrected version: The author's interest in contemporary politics, and particularly in the marginalization of women in the political arena, comes increasingly to the fore in later novels. Also: None of the brothers seem to seek independence from the mother. 'None' is an abbreviation of 'Not one', so is singular. Correct version: None of the brothers seems to seek independence from the mother. Remember that the apostrophe ‘s’ needs special attention, since its position can alter meaning dramatically. Mainly it is used to denote possession. If you have difficulty determining where to place an apostrophe to indicate 17 possession, turn the phrase around using 'of' (the Italian possessive construction), and place the apostrophe at the end of the resulting phrase, e.g. Morantes (?) novels: the novels of Morante > Morante's novels the hermetic poets works (?): the works of the hermetic poets > the hermetic poets’ works In the above examples, misplacement of the apostrophe would change the meaning of the phrases: Morantes' novels would be the novels of an author named Morantes the hermetic poet's works would be the works of one poet, not of a group The apostrophe ‘s’ is not used when ‘it’ is used possessively. e.g. The dog was large and fierce; its name was Hercules. When ‘it’s’ is used, it is an abbreviation for ‘it is’ and the apostrophe indicates that a letter has been omitted (compare also ‘don’t’ for ‘do not’ etc.). The other use of the apostrophe - to indicate omission - is used for abbreviated forms, and, since they are colloquial, they are generally not appropriate for use in a formal piece of writing. In your essays, use do not rather than don’t, is not rather than isn’t, etc. Gender and inclusiveness. The English language has historically used ‘man’ and ‘his’ as universal referents, not only in connection with males (‘God made man in His own image. Male and female created He them’). It is still quite correct to do so, in expressions including ‘as a reader, one needs to have his own opinion on this matter’. However, feminist readers and writers have increasingly objected to this usage, which they feel excludes the female gender. Various solutions (none of them quite satisfactory) have been proposed, ranging from the most extreme one of having the female pronoun stand in place of both male and female (‘The firefighter drove her lorry to the station’) to the more moderate—but rather confusing—one of interchanging ‘he’ and ‘she’, ‘him’ and ‘her’, etc. (‘The reader is faced with a challenge at this point: she must imagine for herself the sequence of events which has occurred during the lapse in the narrative. [Then later in the essay:] It is questionable whether the author of an ‘open’ text allows his [referring to the author] reader genuine freedom of interpretation, or whether her [referring to the reader] responses are to some extent determined.) A more cumbersome solution is to use both masculine and feminine pronouns each time the referent is not determined (‘The reader is faced with a challenge at this point: s/he must imagine for her-/himself the sequence of events which has occurred during the lapse in the narrative. [Then later in the essay:] It is questionable whether the author of an ‘open’ text allows his/her reader genuine freedom of interpretation, or whether the latter's responses are to some extent determined. [‘the latter’ makes clear that the reader is the subject of this clause, since ‘his/her’ may be ambiguous in this instance, potentially referring to author or reader.]). One elegant way of resolving these sticky passages is to change everything to the plural if one really objects to using the masculine pronoun (‘Readers are faced with a challenge at this point: they must imagine for themselves the sequence of events ... It is questionable whether authors of ‘open’ texts allow their readers genuine freedom of 18 interpretation, or whether the readers’ responses are to some extent determined.) Feminists also object to the universal use of words such as ‘man’, ‘men’, ‘mankind’, preferring in their stead ‘human beings’, ‘people’, or ‘humanity’. You should make your own decision on the matter. Religion. Out of reverence to the deity, or because of their religious background, some authors or students feel uncomfortable writing out ‘God’ in their essays; they often write it as ‘g-d’, which is perfectly acceptable. Some like to capitalize pronouns referring to the deity (‘God’s creation shows His power’) whereas others leave them in lower-case. Either usage is correct. ii) Pay close attention to punctuation. Generally speaking, students tend to underpunctuate rather than the opposite, so when writing and re-reading your essay, look to add rather than to remove punctuation. As a rough guide, any point at which you would pause when reading a sentence aloud should be marked by a punctuation mark: a comma for a short break, a semi-colon to separate items in a list or to make a sharper break, a colon to elaborate or to introduce further related comment, a full stop to end one idea or example and introduce a further one. Paragraph breaks provide for starker separation of different points or components of your argument, but ensure that the connection between one paragraph and the next is clear to your reader. Double quotation marks should only be used for speech or quotation within a quotation, e.g. The story opens with a seasonal vignette: 'He slid down the chimney and said, "Merry Christmas!"'. Use single quotation marks a) to quote from texts or b) to cite lesser-known or very specific theories, movements, genres, especially if their name is not in English - e.g. 'cinema d'auteur'. In the case of (b), use quotation marks sparingly, and an alternative is, as with 'vignette' in the example above, to italicize the word. Never use quotation marks (single or double) simply to highlight a word or concept. Never use quotation marks (single or double) when writing the title of a book, film, journal, etc. Minimize your use of exclamation marks. Since exclamations are a feature of spoken rather than of written language, they should, strictly speaking, appear in your essays only within quoted speech. Do not use an exclamation mark to signal something amusing or ironic: careful use of syntax and/or vocabulary can express this quite adequately. iii) There are some rules of thumb which can help in spelling. Here are some of them. When ‘full’ is added to a word, you change ‘full’ to ful’, e.g. helpful, cheerful. When a word ends in a consonant followed by ‘y’, you change the ‘y’ to an ‘i’ before adding ‘ed’, e.g. tidy, tidied. When a word ends in ‘-ce’ or ‘-ge’, you keep the ‘e’ when adding ‘-ous or ‘-able’, e.g. peace, peaceable; courage, courageous. When ‘ie’ or ‘ei’ sound like ‘ee’, as in keep, then ‘i’ comes before ‘e’ except after 19 ‘c’, e.g. field, niece, but receive and ceiling. When a word ends in a vowel followed by the letter ‘l’, you double the ‘l’ before adding ‘-ed’ or ‘-er’ or ‘-ing’, e.g. travel, travelled, traveller, travelling Exception: parallel, paralleled. The final consonant of monosyllabic words where the final consonant is preceded by a vowel is also doubled before ‘-ed’, ‘-er’ ‘-ing’, e.g. stop, stopped, stopper, stopping; rob, robber, robbing; run, running; hot, hotter. But there is no doubling when there are two vowels or another consonant before the final consonant, e.g. feel, feeling; halt, halting. '-ise' and 'ize': You may use either, but MHRA guidelines prefer the '-ize' version. Whichever you choose, be consistent. Note, if using '-ize', that there are some verbs which always end in '-ise'. The MHRA Style Guide gives a list of these, but commonly-used examples are: advertise advise comprise compromise devise enterprise improvise revise supervise surmise surprise also: analyse For students of Italian there are further problems concerning spelling. In the first place, it is a commonly known phenomenon that learning a new language (or indeed a new subject) can sometimes dislocate previous knowledge, so you may find that the acquisition of Italian leads you to some uncertainties in English. It is usually the case that the more competent you become in the new subject, the more stable your previous knowledge becomes. There are, however, real confusions that can be made between the two languages in matters of spelling. Here are a few of them. The single ‘m’ and the double ‘m’: ‘image’ in English, ‘immagine’ in Italian; but ‘communism’ in English, ‘comunismo’ in Italian; ‘communicate’ in English, ‘comunicare’ in Italian. Italian does not use ‘y’ as a vowel so you must remember that English does e.g. ‘psychiatrist’ in English, ‘psichiatra’ in Italian. Italian does not use ‘ph’ as ‘f’ so you have to remember that English does e.g. ‘philosophy’ in English, ‘filosofia’ in Italian. As language students, it is good to notice these differences as you learn. Note down differences of this kind as you become aware of them and build up your own list. When in doubt about a word, look it up in a dictionary and then learn it. Note that misspelling can sometimes change the meaning of a word: e.g. ‘discreet’ means judicious, circumspect; ‘discrete’ means separate, distinct. Use the ‘spell check’ on your word processor, but remember that it will not highlight words that are correct in themselves but are not correct in context. 20 e.g. She bought a pear [pair] of socks and stuffed them in her bat [bag]. Also bear in mind that the ‘spell check’ offers some crazy solutions of its own (e.g. the 'Word' ‘spell check’ does not accept the word ‘Italianist’ and offers ‘Stalinist’ in its stead). Remember that some Italian words require accents, so make sure you put them in before handing in the essay. In 'Windows', accents can be found in <Character Map>, amongst the <Accessories> under <Programs>. Select the accented letters you need and then copy and paste them into your text, ensuring that font sizes, italicization, etc. agree. (You may add accents neatly by hand, if you prefer.) Note: If you are dyslexic, or think you might be, make sure you tell your tutor. There are special examination arrangements for dyslexic students. 14. Correcting and checking your essay It is a good idea to read your essay through a number of times before submitting it. The following are points to look out for: Check that references and quotations are accurate; check that Italian quotations have the correct accents. Check that all book titles are italicized or underlined. Check that the punctuation you have used is adequate: if you need to read a sentence twice in order to grasp its meaning, then add punctuation or re-phrase the sentence (possibly making it two or more sentences) Cut out unnecessary repetitions, excess adjectives, and empty phrases. A part of the process of clarifying your own thinking in writing is to phrase one concept in a number of different ways. On re-reading your essay, you may well find that one such phrase conveys the concept adequately, and the others merely burden the essay. Check that you have kept to the word limit for the essay. Most tutors allow a little flexibility but on the whole the word length is advice that is meant to be followed. If your essay exceeds the limit, comb through it for sentences or examples which only bolster your argument, rather than genuinely building it. Make sure that you have been clear. It is very easy when you have been working on a topic for some time to assume that the reader is on your wave length, or that, because the tutor who will read your essay ‘knows all of this’, there is no point in writing out the argument in full. Ensure that all the steps in your argument are exposed. It is, therefore, very important to leave enough time to read through your work more than once, preferably in hard copy (i.e. on pages of paper rather than on the screen). If at all possible, leave the finished essay for a day or two and come back to it with fresh eyes. Bear in mind when planning your time that the last things - checking the quotations, references and spelling - always take longer than you think they will. 15. Assessment Criteria These criteria are used when marking essays of all kinds: assessed, 'non-assessed', and exam (see section 17 below for additional comments on exam essays). There are three 21 categories of assessment: i. Factual content: the selection of relevant, detailed and accurate data, demonstrating a fundamental knowledge and understanding of the subject, and showing evidence of broader individual awareness. ii. Analytical skills: the ability to interpret the factual material critically and creatively, evaluating accepted judgements in the light of independent analysis, so as to form a coherent, scrupulously-structured argument which responds to the question with originality. iii. Presentation: the expression of the argument in lucid, fluent prose of an individual and engaging style. Spelling, punctuation, and grammar, should be correct, and the essay should be accompanied by a full and accurate bibliography (and notes where necessary). The weight given to each of the three categories when assessing individual essays varies slightly from year to year, reflecting the development we aim to encourage in each student’s intellectual abilities. Whilst a sound and detailed knowledge of the core texts and their contexts remains an essential component of any essay, credit given for this category will decrease after year one, as the focus of learning and teaching shifts to the more advanced skills of critical analysis, creative argumentation and engaging presentation. Crudely speaking, category i is prioritized in the first year, with ii and iii gaining prominence in subsequent years, and ii becoming the main priority in the final year. However, no essay at any level can be successful unless the skills encompassed in each of the three categories are demonstrated to the best of the student’s ability. 22 The following table describes, with reference to the above categories, the features of an essay in each 'class' or band of marks: % Class Description 80+ I Comments An essay which has all the qualities of an essay in the 70-79 bracket, all to an outstanding level, may be awarded a mark in this bracket. A genuinely exceptional and memorable piece of work would merit such a mark. 70-79 I i. Exceptional and relevant detail, judiciously employed. Evidence of independent research, and illuminating reference to material beyond the immediate subject. Marks in the upper 70s are awarded to essays which exhibit qualities ii. A creative and original argument, which is described in one elegantly structured and responds challengingly or or two of these subtly to the question. categories to an outstanding level. iii. The presentation is stylish and engaging, without sacrificing clarity and accuracy in spelling, bibliography etc. 60-69 II:1 i. Excellent understanding of the relevant material, Marks in which has been carefully selected with intelligent 60s denote some contextual reference. originality or flair, but only in ii. A coherent and logical argument, responding isolated moments. thoughtfully to the question, and demonstrating a Marks in the lower sophisticated synthesis of ideas. 60s are awarded to essays which are iii. The presentation is clear and efficient, with full and competent very few errors of spelling, etc. but rely heavily on received opinion. 50-59 II:2 i. Sound understanding of the core material, some of which has been inadequately or disproportionately covered in the essay. Marks in the upper 50s are awarded to essays which contain some ii. The argument is competent, but unclear or work of II:1 insufficiently developed in parts. The essay does standard, but are not engage consistently with the question, and inconsistent. tends to be descriptive rather than analytical. Marks in the lower 50s are awarded to iii. The presentation is satisfactory, but the syntax essays which are is pedestrian, the range of vocabulary limited, or of III standard in a the spelling poor. Bibliography may be inadequate. key area, such as relevance or structure. 23 40-49 III i. Understanding of the core material is patchy or limited. Marginally relevant issues may have received disproportionate coverage, suggesting recycling of material. Marks in the upper 40s are awarded to work which is of II:2 standard in limited aspects. ii. Unstructured description predominates, with Marks in the lower little attempt to analyse facts or to formulate a clear 40s are awarded to response to the question. work which is barely acceptable iii. The presentation is poor, with errors of at this level of grammar and spelling, and inept use of paragraphs. study, but which shows scope for improvement. 30-39 Fail i. Limited knowledge of the subject is demonstrated, but this is either extremely superficial or isolated in only one area. The essay may contain good material, but related to a different question. Work which contains substantial amounts of paraphrasing of secondary material falls into this class. ii. The sense of the essay is extremely difficult to grasp, and it does not respond to the question in an immediately identifiable way. iii. The presentation renders the essay all but incomprehensible and includes very basic errors. The style may be inappropriate to the task, e.g. too colloquial. 0-29 Fail i. The essay demonstrates virtually no knowledge or understanding of issues central to the topic. Work which contains substantial amounts of plagiarism of secondary material falls into this class. Marks of below 20 are normally awarded only in cases where nothing legible has been submitted. ii. The essay fails to answer the question, either through neglect or deliberate manipulation in order to recycle material. The essay may have a conspicuous argument, but fabricated from a highly insubstantial or inaccurate impression of the subject. iii. Brief, incoherent notes rather than an essay. 24 16. Return of essays Do not consider the task of writing an essay finished when you hand it in! In the case of both assessed and 'non-assessed' essays (but not of exam essays), you will be offered the opportunity to discuss your essay in person with your tutor, in addition to his/her written comments on the comments sheet or script. Take this opportunity: as indicated in the introduction, expressing your ideas in writing is a skill which you will develop gradually over the years of your university study, and this development will be optimized by listening to and digesting an experienced reader's feedback. Also, take the time to re-read the essay in the light of the marker's or markers' comments, and note your strengths and weaknesses, any spelling or grammatical errors you frequently make, etc. 17. Examination essays The Departmental Assessment Criteria (see section 15 above) apply also to exam essays, but the different skills demanded in examination conditions mean that the weighting of the categories of assessment is adjusted slightly. Constraints of time and memory mean that an exam essay will probably include less peripheral detail than a course-work essay, and the presentation may be less elegant. However, the intensity of the circumstances should facilitate work which is concise, powerfully-argued and imaginative. These considerations mean that category ii (analytical skills) will normally be the prominent one in assessment of exam essays, but - as stressed above no essay at any level can be successful unless the skills encompassed in each of the three categories are demonstrated to the best of the student’s ability. The following are some recommendations for writing exam essays: Plan your essay. The limited time available to write an essay in exam conditions makes careful planning MORE, not less, important. Do not fall into the trap of spotting a key-word, such as 'feminism' or 'Resistance', in a question, and, having done extensive revision on this aspect of the topic, writing your planned essay on it, without reading the question properly. Ignore your watch and read the questions thoroughly, determining what exactly each is looking for. Then, having selected one you feel able to answer well, search through the mental files for information you have accumulated throughout the module and revised, and note down which of it you want to use, and in what order. A delay in starting to write which is spent on planning is not time wasted; a pause mid-way through writing to wonder what you want to say next or to realize you should have included your next point three paragraphs earlier is time wasted. Follow the rubric. Make sure you adhere to any restrictions on the material you may use, any instructions regarding the number and type of questions to answer, any stipulations about the number of texts or examples to use. Failure to adhere to the rubric is penalized. Answer the question. Of course, this is a crucial recommendation for writing any essay, but in exam conditions you have less time than normal, so need to be more succinct, more direct. Generally, you have less time to convince your reader so your argument needs to be as strong as possible - though, as always, supported by sound knowledge of the topic. Complete your essay. This is easily accomplished if you have planned your essay well: even if you notice that time is short and you still have several points to make, with a plan in front of you, you can prioritize certain points and leave out or 25 minimize others. Examiners will recognize that an essay has had to be hurried because of time constraints, but nevertheless, a complete essay, with a brief but emphatic conclusion, will generally be more successful than one which presents an interesting but abruptly truncated argument. View exam essays positively. It is easy, but misguided, to feel that the task in an exam is to produce the same essay as in non-exam conditions, but with fewer material resources to hand and less time. Viewed like this, it seems you can only under-perform in exam conditions. However, the exam is a different sort of task from a mid-term essay. You are being asked, at the end of a period of intensive study, to demonstrate that you have digested and assimilated a great deal of information on a subject, which you can refer to in order to produce a wellinformed and individual synopsis of a certain aspect of that subject. Your only resource is your own mind, and the intensely concentrated environment of the exam is an opportunity to show off what it can do. Consider the absence of books and of time to ponder as a liberation. 18. Commentaries or context questions In terms of content, a commentary is more clearly delimited than most essays, in the sense that the 'raw material' is provided, and you should use it. This does not, however, mean that you should restrict your analysis entirely to the given text. You should put it in context by referring to other parts of the novel, poem, play, collection of poems or stories, from which it derives, but always maintaining the emphasis on the extract itself. In terms of analysis, a commentary should be a close critical discussion of the given text, displaying your knowledge of the work as a whole and of critical opinion in general (as in an essay), but foregrounding your own individual interpretation of the extract. It should not be a transcription in your own words of the given text. In terms of presentation and style, a commentary should be produced in the same way as an essay, i.e. composed of full sentences in coherent paragraphs, and structured fluently. It should not be a list of comments on disparate features of the given text. There is no correct way to write a commentary, as there is no correct way to write an essay, but it should include the following: An introduction, placing the extract in context. State where it comes from (author, work, chapter/canto, etc.) and describe briefly events or information immediately preceding or following the extract. An account of the theme/s of the extract. Describe the general ideas underlying the passage, and situate them in relation to the development of the thought structure of the entire work. Detailed analysis of content, form and style. Analyse what is expressed by the author here - ideas, facts, opinions -, in relation to what is said elsewhere in this text, or in the author's work as a whole, or in the genre/period as a whole. Analyse how it is expressed - form, structure, language, imagery, syntax, rhythm -, in relation to form and style used elsewhere in the text, author's work, genre, period, 26 etc. A conclusion. Summarize the main features of the given text, assessing its significance within the text as a whole, within the author's work, etc. The detailed analysis is clearly the kernel of the commentary, where you are expected to demonstrate your immediate skills of textual analysis alongside your more general knowledge of the whole work, or author, or genre, in question. Whether this part is executed line-by-line, point-by-point, separated into content, form and style, etc. will depend on the particular extract and on your own personal preferences. You should aim to produce an expert reading of the given text within its broader context. Think of what a commentator does when commentating a football match on television. S/he knows that the viewer can see the match as well as s/he her-/himself can - just as the reader of your commentary has the given text in front of him/her. The commentator's job is to interpret the action on screen so as to enable the viewer to get the most out of what s/he sees, by adding expert knowledge and opinion on each individual player's past performance, aptitudes and weaknesses; on each team's past record; on the coaches' attitudes to this match and to their respective players; on particular strategies or moves; on the significance of this particular match for each team, for the championship, for British/European/world football, etc. As commentator on a piece of text, your task is similarly to enhance your reader's experience of the given text, by adding information and opinion on characters and events within the passage, as related to their appearance earlier or later in the novel or poem; on the author's or narrator's position within this extract, as related to elsewhere in the full text; on stylistic features; on the significance of this passage within the whole novel, poem, or collection, or within the author's work, or the genre, or the period, etc. The football commentator will always 'keep his/her eye on the ball', i.e. foreground what is happening in the match, but will aim also to fill in the background. You too should maintain a focus on the given text, but aim to place it in its context. 19. Dissertation The dissertation lies at the opposite end of the spectrum to the exam essay. Here, your ability to exploit a great range of resources and an extended period of study is tested. Generally speaking, all the points about essay-writing in this guide apply to the writing of a dissertation, but in accentuated or extended form. Listed below are those points, with specific comments regarding the dissertation: Choosing the topic. This needs careful thought and discussion with your tutor. You will probably begin research with a general topic in mind, and narrow it progressively. Whilst your specific title is likely to be revised a couple or a number of times, it is important to mark out the territory of your research reasonably early, in order to concentrate your efforts. Reading. This will fall into the same categories of primary and secondary material, but both will be vastly extended. In a longer research project, you will find that you cannot be too selective about texts, but are obliged to read, for example, all the major critical works on an author, or a number of theoretical approaches. You may 27 often be reading material in order to exclude it from your dissertation, rather than to include it. Resources. You are likely to use the resources of a wider range of libraries, and to make use of inter-library loans. You will need to be careful to be up-to-date with recent research on your topic. The MLA (Modern Languages Association) bibliography is a useful tool. Note-taking. Given the amount of notes you will be making, it is especially important to organize your notes clearly. Take detailed references of materials consulted, especially if they are borrowed from another library, and therefore difficult to check at a later date. Organizing your essay. Structure is of enormous importance in a longer piece of writing. Produce a plan of your dissertation early on and discuss it with your tutor. Your work is likely to be divided into chapters or sections, so make sure these interleaf coherently, and, if you make any changes to the work, especially in finalstage revising and editing, be very careful to check that your overall structure remains sound. Use of secondary sources. A dissertation is a piece of scholarly research, in which it is necessary to situate your argument in relation to secondary sources. The nature of your topic will influence your use of these sources: whether you are in dialogue with one major critical opinion throughout, or cite and discuss various sources eclectically. Again, your tutor will guide you. Plagiarism. Since the dissertation is the equivalent of a whole module, in terms of CATS, it is vitally important that you avoid any use of source material which might be construed as plagiarism, thus reducing or cancelling your mark for the module. Referencing. The systems described above are valid also for dissertations, but you should consult the MHRA guidelines directly for more details. Footnotes or endnotes will be a necessary adjunct to the text. Generally speaking, footnotes in a longer piece of scholarly writing allow you i) to provide supporting evidence for your argument in fully referenced form, without clogging up the main text, and ii) to outline the peripheries of your research and of your argument, indicating further sources which have not been directly relevant to your research, or providing additional material for readers who may have slightly different interests in the topic from your own. However, your use of footnotes needs to be carefully controlled, so as not to burden or disrupt the argument in your main text. Your tutor will give you guidance on this. Presentation, including quotations, style etc. Given that you have a full year to produce your dissertation, you will be expected not only to have done thorough research and to have thought out the topic fully, but to present your work in publishable form. That is, the grammar, punctuation and spelling should be as close as possible to flawless, your vocabulary and style should be varied, elegant and precise, and the presentation of the document should be of professional standard. See the MHRA guidelines and the departmental 3rd & Final year handbook for details of how to present your dissertation. Correcting and checking your dissertation. It follows from the above that the time allowed for checking and correcting your dissertation, on top of time spent editing 28 and revising the text in terms of content and structure, needs to be generous. You should expect to print out the whole text at least twice before submitting it. It is advisable to ask another or others to proof-read the text for you, since such intimate knowledge of it as yours often blinds you to obvious typographical errors. Check accents, punctuation, layout, etc. meticulously. Use the tools found under <Text Flow> (found in 'Word' via <Format> on the tool bar, then <Paragraph>) to avoid titles or single lines of text being separated over page breaks from the paragraph which follows them, and other such discrepancies. Assessment criteria. The criteria for marking dissertations are broadly the same as those for marking shorter essays, with the specific amendments and emphases outlined in 1-15 above. Your tutor will advise you of the particular qualities your work should demonstrate, but in general, the examiners of your dissertation will be looking for evidence of broad and thorough research, of a genuine understanding on your part of the topic, of critical skill and intellectual creativity in building your argument and expressing your interpretation of the subject, and of a professionalstandard rigour in presenting your work. 20. Suggested further reading G.V. Carey, Mind the Stop: A Brief Guide to Punctuation, rev. ed. (Harmondsworth, 1976) David Crystal, Rediscover Grammar (London, 1988) Department of English & Comparative Literary Studies, Essay Writing & Scholarly Practice (available from the English departmental office, Room 502. This guide contains a useful section on ‘Common Errors in Grammar, Punctuation and Syntax’ and a list of ‘Commonly Misspelt Words’) MHRA, Style Book, 4th edn. (London, 1991) on sale in the University bookshop or from Centre for British and Comparative Cultural Studies, Room H104. Essays: by reading critical analyses or expositions by other writers, you will discover techniques of argumentation, exemplification, expression, punctuation, and items of vocabulary, which you may find effective, engaging, inspiring, dull, irritating, opaque. A good quantity of good quality reading will help you develop your essaywriting skills. Acknowledgements A number of people have made contributions and suggestions which have helped in the writing of this booklet and to whom I am most grateful. They include Loredana Polezzi, Judy Rawson, and Sergio Sokota from the Department of Italian in the University of Warwick and Professor Gino Bedani, Professor of Italian, University College, Swansea. Jennifer Lorch, for the Department of Italian September,1995 Revised, July, 1996. Revised and expanded by Jennifer Burns, August 2000. Reprinted August 2001, September 2002. Revised by David Lines, 29 January 2008 (any comments or amendments to be addressed to me).