H A B ARMFUL

advertisement

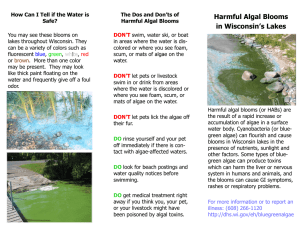

The Beach Manager’s Manual HARMFUL ALGAL BLOOMS WHAT ARE HABs? Harmful algal blooms, commonly referred to as HABs, are an environmentally complex problem throughout the world. When algae grows rapidly in a confined area, grows to the point where a microscope is not needed to see it, or when it grows rapidly to form a dense population, it is referred to as an algal bloom. Blooms can be found within most bodies of water throughout the Great Lakes. They thrive in shallow, warm, non-moving bodies of water like bays, smaller lakes and ponds. A HAB, is a bloom of blue-green algae that contains toxins. HABs can cause fish kills, foul up nearby coastlines and produce conditions that pose health risks to aquatic life, as well as humans. Figure 1. Harmful algal bloom formation in the nearshore region. (Photo: D. Straw) ABOUT CYANOBACTERIA Blue-green algae are also referred to as cyanobacteria. These organisms have been around for thousands of years and are naturally occurring. It is very important to note that not all algae produce toxins; those that don’t are not considered harmful. Cyanobacteria act like algae in that they photosynthesize and utilize light and nutrients, such as phosphorous and nitrogen, for 2 The Beach Manager’s Manual growth; however, they are bacteria. High nutrient levels, warm water temperatures and high light levels — or a combination of all three factors — may stimulate the rapid reproduction of cyanobacteria until it dominates the local aquatic ecosystem, forming an algae bloom. Cyanobacteria can survive in many aquatic environments ranging from deep-sea vents in the Atlantic Ocean to the pond in your local park. Cyanobacterial blooms vary in appearance and can appear as foam, scum, or mats on the surface of freshwater lakes and ponds. These blooms may manifest in a variety of colors, including bluegreen, bright green, brown, or red.1 Visual observation of a water body alone will not confirm the presence of cyanobacteria, nor can it confirm the presence of toxins in the water. Examination of a water sample and identification with a microscope will confirm the presence of cyanobacteria. Further analysis is necessary to determine toxicity. HOW AN ALGAL BLOOM FORMS Blooms form when a specific type of algae increases until it dominates the aquatic system (Figure 1). The formation of a bloom is also influenced by the physical and biological characteristics of the water, as well as the season. A B C D E Figure 2. (a) Microcystis sp.; (b) Anabaena flos-aquae; (c) Anabaena circinalis; (d) Aphanizomenon flos-aquae, and (e) Cylindrospermopsis raciborskii. The conditions that contribute to bloom formation include: n he presence of nutrients such as T nitrogen and phosphorus. n ater temperatures between W 15° and 30°C. n pH levels between 6 and 9. n Late summer or early fall. While heavy rainstorms and high water flows increase runoff and increase nutrients in the water, the increased turbulence is not favorable for the formation of a cyanobacterial bloom. The initial impact of a rainstorm or other turbulence displaces the cells in the water column before they can become a bloom. TOXINS IN ALGAE As stated previously, cyanobacterial blooms may be the cause of a wide range of problems for recreational users and animals living in the aquatic environment because they produce toxins. People may come into contact with toxins by ingesting contaminated waters or through recreation. Overall, 50-75 percent of bloom strains produce toxins and often there is more than one toxin present. The presence of more than one toxin is due to multiple algal species present in the water sample.2 There are more than 40 freshwater species of toxic cyanobacteria. The most common species of cyanobacteria in the Great Lakes that can produce toxins are: n M icrocystis aeruginosa n A nabaena circinalis n A nabaena flos-aquae n A phanizomenon flos-aquae n C ylindrospermopsis raciborskii The three main classes of toxins produced by these cyanobacterial species are: 1) N erve toxins, also called neurotoxins 2) Liver toxins called hepatotoxins 3) Skin toxins called dermatotoxins The dermatotoxins cause itching, rashes, and other allergic reactions. All cyanobacteria are dermatotoxins (i.e., produce skin irritants). Also, all of these toxins may cause gastrointestinal distress. HARMFUL ALGAL BLOOMS 3 Table 1. World Health Organization (2003) provisional guidelines for threats to human health from recreational contact with cyanobacteria4. Human Health Risk Cell Concentration (per milliliter) Chlorophyll a Concentration Low < 20,000 cells 1-10 ppb Moderate 20,000-100,000 cells 10-50 ppb High > 100,000 cells Visible scums EFFECTS OF TOXINS The effects of these toxins vary widely among individuals. They are dependent on age, health and the sensitivity of the individual to the toxin. The World Health Organization (WHO) has put forth recommended guidelines for algal toxin exposure for humans, which translate into 1µg/L for drinking water and 20 µg/L for recreational water contact (Table 1).3 The WHO developed provisional guidelines to identify concentrations of Microcystis sp. and the toxin microcystin that may impact human health. Potential risk to human health from recreational contact is considered low at microcystin concentrations up to 4 ppb and moderate at 20 ppb. SYMPTOMS OF HABs EXPOSURE HUMANS: numbness of lips, tingling in fingers and toes, dizziness, headache, rash or skin irritation, abdominal pain, diarrhea, and vomiting. PETS: weakness, staggering, convulsions, difficulty in breathing, and vomiting. 4 The Beach Manager’s Manual A dead fish resulting from toxins. (Photo: Jennifer Graham, USGS) IMPACTS ON ANIMALS Fish that are impacted by cyanobacteria may develop skin lesions, making them vulnerable to infection and disease. Toxic blooms may also impact gill functioning. Gas exchange across the gill surface is reduced by mucous over the gills.5 Some dog and livestock deaths have been attributed to the ingestion of toxic water. The extent to which cyanobacterial toxins move up the food chain (e.g., through zebra mussels and fish) is currently being researched in the Great Lakes. IMPACTS ON HUMANS Humans who come into contact with a HAB will likely experience mild skin irritation or a rash. Some cyanobacterial blooms of Microcystis, Anabaena, and others have been linked to incidences of human illness in the United States as well as other countries. Reported instances of health impacts associated with algal toxin exposure are limited in the public health community. This is due to the lack of reporting by recreational users who become ill after contact with the algal toxin, the lack of knowledge of symptoms associated with HAB exposure, as well as the lack of training from medical professionals on symptoms and diagnoses. Symptoms of algal toxin exposure can be similar to those of the common cold, flu, and food poisoning, which could contribute to the lack of reporting or to misdiagnosis. Because of possible health hazards, experts highly recommend that people avoid skin contact with water that has visible blooms — whether they are known to be harmful or not. In addition, water bodies that are treated with algaecides, may release algal toxins during cyanobacterial die offs, even if no cyanobacteria is visible in the water. It is not recommended that HABs be treated in this manner as it may cause worse repercussions for human and animal health than simply waiting for the HAB to dissipate. Some beaches post warning signs to alert the public of possible cyanobacteria in the water. However, because HABs are not regulated or monitored for toxins, the majority of beaches in the Great Lakes do not post warning signs for HABs. Grand Lake St. Marys Water Quality Advisory Sign, 2009. (Photo: Linda Merchant-Masonbrink, Ohio EPA) HARMFUL ALGAL BLOOMS 5 Tom Archer CLIMATE CHANGE AND HABs It is generally accepted that the frequency, intensity, and duration of HABs in all aquatic environments are increasing globally,6 & 7 which may be, in part, due to climate change. However, the link between climate change and HABs is poorly understood due to limited research.8 Scientists anticipate, however, that climate change will produce new extremes in climatic conditions. This may lead to warmer surface water temperatures, increased nutrient (carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorous) loadings, altered hydrology (more frequent floods and droughts), changes in thermal stratification (temperature or density layers in the water), changes in the duration of ice cover, and other environmental alterations, which will have a significant impact on algal ecology. Growth rates, different species present in the water, and frequencies of algal blooms will likely be impacted. 6 The Beach Manager’s Manual Minnesota Pollution Control Agency Algal seasonal successions in aquatic environments are changing, with cyanobacteria showing up earlier and staying longer throughout the seasons. If bloomforming species become prevalent, the result will likely be increased production of toxins that will have adverse impacts on drinking water treatment and public health. Bloom-forming species are associated with toxin production, taste and odor compounds, and chemical byproducts after wastewater treatment. Therefore, as blooms become more frequent, there will be need for increased water monitoring plus increased treatment at water treatment plants. This all adds up to increased costs. For more information on climate change and HABs, see the American Association for the Advancement of Science annual meeting synopsis concerning climate change.9 FACTORS INFLUENCING THE GROWTH OF HARMFUL ALGAL BLOOMS Illustration: Michigan Sea Grant HOW CAN I KEEP MY BEACHGOING PUBLIC SAFE? If there are visible layers of algae, the water is green or discolored, or a HAB warning has been posted, it is best to have beach visitors avoid contact with water. You can provide the following tips to your visitors to help protect them and their pets. n After swimming in a lake, pond, or river, always rinse off. n Also, rinse pets that have been swimming. n Don’t drink water from lakes and rivers, as it may contain algal toxins or pathogens and bacteria. Boiling water will not get rid of the toxins. n Make sure pets do not drink from a water source that may have contact with a HAB. n Pay attention to warning signs posted at the beach. n If anyone becomes ill after swimming, they should seek medical attention immediately. Seek veterinary assistance if a pet appears ill. HOW CAN WE PREVENT HABs? Beach managers and other community members can encourage their neighbors to follow a few steps to reduce the development of HABs. n Reduce or eliminate the use of fertilizers. If fertilizers have to be used, encourage the community to use low- to no-phosphorous products. n Check septic systems regularly and make sure the tanks are emptied every two to three years. Improperly functioning septic tanks can contribute to algal blooms by releasing nutrients into the waterway. n Eliminate the use of products like soaps and dishwasher detergents that contain phosphates. n Wash cars on the lawn so the runoff filters through the soil instead of running straight off of pavement and to the gutters. n Encourage the use of rain barrels to reduce runoff. n Consider installing pond aeration systems in small ponds and lakes that have had algal blooms in the past. n Promote native and natural landscaping around waterways and backyard ponds. Tall grasses help filter some additional nutrient runoff — and they discourage Canada geese from taking up residence. Goose fecal waste contributes to excessive nutrient loading in water. HARMFUL ALGAL BLOOMS 7 Minnesota Pollution Control Agency REFERENCES ADDITIONAL INFORMATION www.cdc.gov/hab/cyanobacteria/facts.htm tidesandcurrents.noaa.gov/hab whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/1998/WHO_EOS_98.1_(p95-152).pdf www.cop.noaa.gov/stressors/extremeevents/hab/current/ noaaHab.html World Health Organization (WHO). 2004. www.who.int/water_sanitation_ health/resourcesquality/toxcyanchap5.pdf. Accessed on March 10, 2011. World Health Organization (WHO). 2003. Guidelines for safe recreational water environments, vol. 1: Coastal and fresh waters. World Health Organization, Geneva. Center for Integrated Marine Technologies (CIMT). 2006. Harmful Algal Blooms (HABs). www.cencoos.org/documents/about/HABs_Factsheet.pdf (accessed on March 10, 2011). Glibert, P. M., D.M. Anderson, P. Gentien, E. Graneli, and K.G. Sellner. 2005. The global complex phenomena of harmful algae. Oceanography. 18:136–147. Van Dolah, F. M. 2000. Marine Algal Toxins: Origins, Health Effects, and Their Increased Occurrence. Environmetal Health Perspective, 108:133–141. Moore, S. K., V.L. Trainer, N.J. Mantua, M.S. Parker, E.A. Laws, L.C. Backer and L.E. Fleming. 2008. Impacts of climate variability and future climate change on harmful algal blooms and human health. Environmental Health, 7(Suppl2); S4. http://aaas.confex.com/aaas/2011/webprogram/Symposium73.html www.ocean.us/what_is_ioos www.iisgcp.org ohioseagrant.osu.edu www.seagrant.wisc.edu www.glerl.noaa.gov/res/Centers/HABS/lake_erie_hab/lake_erie_hab.html www.miseagrant.umich.edu/hab www.in.gov/dnr/fishwild/3630.htm dnr.wi.gov/lakes/bluegreenalgae www.odh.ohio.gov/features/odhfeatures/algalblooms.aspx PHOTO CREDITS Figure 1. http://green.kingcounty.gov/lakes/ToxicAlgae.aspx Figure 2. www.whoi.edu/redtide/page.do?pid=16142 Figure 3. All images can be found at Cyanosite (www-cyanosite.bio.purdue.edu) a. Isao Inouye (Tsukuba University) and Mark Schneegurt (Wichita State University); CONTACTS Leslie E. Dorworth Aquatic Ecology Specialist Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant (219) 989-2726 dorworth@purduecal.edu Sonia Joseph Joshi Outreach Coordinator Michigan Sea Grant (734) 741-2283 Sonia.Joseph@noaa.gov b. W ayne Carmichael (Wright State University), Mark Schneegurt (Wichita State University); c. C yanosite (www-cyanosite.bio.purdue.edu); d. Roger Burks (University of California at Riverside); e. Jason Oyadomari. Figure 4. www.utoledo.edu/as/lec/research/wq Figure 5. www.noaanews.noaa.gov/stories2009/ 20090917_ohiohab.html Figure 6. http://toxics.usgs.gov/highlights/algal_toxins 8 The Beach Manager’s Manual: HARMFUL ALGAL BLOOMS MICHU-12-502