The effect of contracted reinforcers on targeted nutrition-related dental behaviors... pediatric subjects

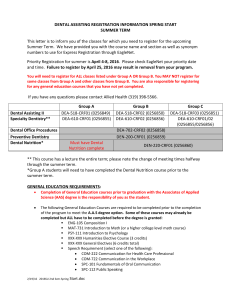

advertisement