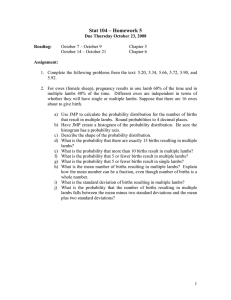

Effects of oral supplementation of ewes with aureomycin and effects... lamb production

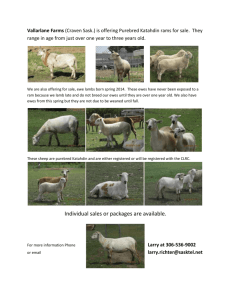

advertisement