A survey of Montana superintendents and school board members attitudes... personal and family living

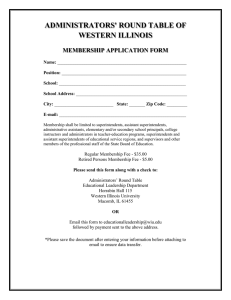

advertisement