Alert K&LNG Environmental Supreme Court Decides What Waters Are Subject to Clean

advertisement

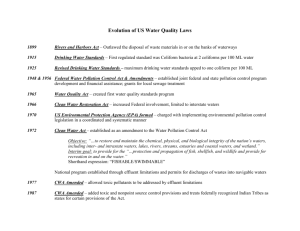

K&LNG JUNE 2006 Alert Environmental Supreme Court Decides What Waters Are Subject to Clean Water Act Jurisdiction In a decision likely to shake some of the roots of wetlands and clean water regulation, the U.S. Supreme Court has tackled the much-debated question of what waters are subject to regulation under the federal Clean Water Act (CWA). Specifically, in a June 19, 2006, decision, the Court sought to define when wetlands are part of “waters of the United States” and trigger permitting requirements. The court’s split opinion underscored one point: that the scope of federal regulation over wetlands and other waters in the United States is not as broad as federal regulators – including the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the Army Corps of Engineers (Corps) – have long maintained. The precise scope of that jurisdiction (and even the questions that guide what defines such jurisdiction), however, remains unsettled. Under section 404 of the CWA1 , a permit is required from the Corps before any person may dredge or fill materials into “waters of the United States.”2 In Rapanos v. United States, the Supreme Court addressed the scope of CWA section 404 jurisdiction over “waters of the United States,” including “wetlands,” for the third time in 20 years. The Court vacated lower court decisions that had broadly interpreted this term to include any area where water existed and could ultimately flow down to a truly navigable water, regardless of how minimal the connection. While only a plurality of justices joined the opinion, it is clear that certain Corps and EPA regulations,3 extending jurisdiction over ephemeral streams and isolated waters with questionable 1 2 3 4 5 6 connections to navigable waters, are either invalid or at a minimum may not have the conclusive reach that federal agencies had asserted and that lower courts had allowed. This Alert addresses the potential pragmatic impacts of Rapanos on permit applicants. The wider-ranging impacts of this decision on questions of federalism, deference to agencies, and other issues will be addressed in subsequent Alerts. BACKGROUND Which bodies of water are “waters of the United States” for purposes of CWA jurisdiction has been the subject of protracted debate since Congress enacted the statute in 1972. The regulatory definition adopted by the Corps and EPA for purposes of issuing dredge and fill permits under section 404 includes all interstate waters, tributaries, and ephemeral streams, and all wetlands adjacent to such waters.4 In a unanimous decision in 1985, United States v. Riverside Bayview Homes, Inc.,5 the Court held that the Corps may assert jurisdiction over wetlands that are “adjacent to” or immediately abut other “waters of the United States” and their tributaries. The Court found the Corps’ assertion of jurisdiction over the wetlands at issue in Riverside Bayview was reasonable in light of the Act's "language, policies, and history," and was thus entitled to deference under Chevron U.S.A. Inc. v. Natural Resources Defense Council.6 33 U.S.C. §1251 et seq. 33 U.S.C. §1344. E.g., 33 C.F.R. 323.1. 33 C.F.R. 328.3(a)(1)-(7), 40 C.F.R. 232.2. 474 U.S. 121 (1985). 467 U.S. 837 (1984). Kirkpatrick & Lockhart Nicholson Graham LLP | JUNE 2006 In 2001, the Court by a five-to-four majority found that the Corps has no authority under the CWA to require permits for filling isolated wetlands that have no hydrological connection at all to “waters of the United States,” but are connected only because migratory birds move in commerce among isolated ponds, holding the wetlands at issue lacked a substantial nexus to navigable-in-fact waters.7 Since Solid Waste Agency of Northern Cook County v. Army Corps of Engineers ("SWANCC"), parties have argued about what the “substantial nexus” language means, including what constitutes wetlands “adjacent” to navigable waters and how substantial the relationship or connection must be to navigable waters or their surface water tributaries. The majority of lower courts have accepted the United States government’s argument that the hydrological connection between the “adjacent” wetlands and a truly navigable water need only be enough to create the potential in theory for pollution from the adjacent wetlands to find its way to a river.8 This broad view of the nexus issue has allowed the Corps to assert jurisdiction over relatively isolated areas. A minority of lower courts have limited Corps jurisdiction to waters that are “truly adjacent” or have a “significant measure of proximity” to navigable waters.9 In 2004, the Supreme Court declined to grant certiorari to resolve this conflict; and numerous cases have ensued in which the central question was whether a “substantial nexus” existed and how to define it. RAPANOS AND CARABELL The decision rendered by the Supreme Court on June 19 addressed two such cases – brought respectively by the Rapanos and Carabell families, involving four Michigan wetlands lying near ditches or man-made drains. The Rapanos case arose when the subject landowner began filling wetlands on three properties to prepare them for commercial development. The Rapanos family declined to obtain Corps permits, thinking that the areas in question were outside of CWA jurisdiction. The United States filed suit in the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Michigan and also pursued criminal charges for the landowners’ failure to obtain CWA permits. The 7 8 9 10 11 2 district court held the Rapanoses liable for filling approximately 54 acres of wetlands on the three properties, after determining that those wetlands were adjacent to tributaries of “traditional navigable waters” subject to regulation under the CWA and that the wetlands shared a hydrological connection with regulated waters. (The government also obtained a criminal conviction against Mr. Rapanos.) The United States Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit affirmed. It claimed to be following the majority rule interpretation of SWANCC, declaring that that ruling did not restrict CWA coverage to “wetlands directly abutting navigable water.”10 The Carabell litigation arose when the subject landowners were denied a Corps permit to deposit fill in a wetland that was separated from a drainage ditch by an impermeable berm. The Carabells sued, but the District Court found Clean Water Act jurisdiction. The Sixth Circuit affirmed, holding that the wetland in question was “adjacent” to navigable waters (even though separated by the berm).11 On appeal from the Sixth Circuit the Rapanos and Carabell cases were consolidated for review before the Supreme Court. In this decision, the Court considered how broadly the Corps could define the term “adjacent” to extend its jurisdiction under the CWA. The Rapanoses argued that the “significant nexus” standard required that contested wetlands have more than a mere hydrological connection to navigable waters. They contended that wetlands should be considered “adjacent” to “waters of the United States” only when the two were “inseparably bound up.” The Petitioners further argued that the history, policies, and goals of the CWA supported the need for a “strict nexus” requirement. Failure to enforce such a strict requirement, they claimed, would create federalism and due process problems. Alternatively, they argued that extensive and ambiguous Corps jurisdiction exceeded Congress’ constitutional power to regulate commerce among the states. The United States contended that Riverside Bayview upheld the Corps’ regulatory determination that “waters of the United States” included both tributaries of navigable waters and wetlands adjacent to all other waters. It further argued that extending Solid Waste Agency of Northern Cook County v. Army Corps of Engineers, 531 U.S. 159 (2001). United States v. Deaton, 332 F.3d 698 (4th Cir. 2003), United States v. Rueth Dev. Co., 335 F.3d 598 (7th Cir. 2003), Headwaters v. Talent Irrigation Dist., 243 F.3d 526 (9th Cir. 2001). In re Needham, 354 F.3d 340, 345-47 (5th Cir. 2003). United States v. Rapanos, 339 F.3d 447, 453 (6th Cir. 2003). Carabell v. United States Army Corps of Eng’rs, 391 F.3d 704 (6th Cir. 2004). Kirkpatrick & Lockhart Nicholson Graham LLP | JUNE 2006 Corps jurisdiction to ephemeral streams and wetlands adjacent to tributaries, as is done in the regulations, is a reasonable interpretation of the CWA necessary to achieve the goals of the CWA because the potential exists for pollution from these somewhat distant areas to move into navigable waters. Thus, the United States argued, its position was entitled to judicial deference under Chevron. The United States also defended Congress’s grant of jurisdiction over such wetlands as an appropriate exercise of power under the Commerce Clause. Under United States v. Lopez12 the government argued, either (1) “waters of the United States” were channels of interstate commerce, or (2) the regulation of those waters constituted an activity having a “substantial effect” on commerce. The Sixth Circuit had agreed with the United States, at one point essentially eliminating the concept of “substantial” from the nexus requirement for adjacent wetlands to be considered part of “waters of the United States.” factors as economics, aesthetics, recreation, and in general, the needs and welfare of the people.” Op at 3.13 ■ "[Thus,] establishing that wetlands such as those at the Rapanos and Carabell sites are covered by the Act requires two findings: First, that the adjacent channel contains a “water of the United States,” (i.e., a relatively permanent body of water connected to traditional interstate, navigable water); and second, that the wetland has a continuous surface connection with that water, making it difficult to determine where the water ends and the wetland begins." Op. at 11. ■ The plurality’s opinion minimized the importance of the phrase “significant nexus”, which the Court had referenced in SWANCC, explaining it was only a characterization of the exercise of discretion required in the Riverside Bayview case to determine the precise point at which wetlands that are adjacent to a navigablein-fact water become “waters of the United States.” ■ Justice Kennedy, concurred in the judgment but strongly disagreed with the plurality’s analysis. He emphasized the “significant nexus” between wetlands and navigable-in-fact water required to assert jurisdiction over the wetlands, stating his view as follows: WHAT DID THE SUPREME COURT SAY? The Supreme Court’s decision was a classic split decision. A plurality of four conservative justices, led by Justice Scalia, provided the lead opinion which sharply criticized the federal agencies’ interpretations of the CWA. Justice Kennedy joined in the result and filed a narrower concurring opinion. The resulting five-to-four majority of the Court vacated the lower court decisions, reflecting the following positions: ■ ■ All five justices supporting the judgment agreed that there must be a “significant nexus” between the area to be regulated and a traditional navigable water, and that the lower courts did not apply that standard properly. The plurality (Justice Scalia, writing for Chief Justice Roberts, and Justices Thomas and Alito) concluded that the Corps had improperly expanded its jurisdiction over the past 30 years by defining “waters of the United States” to include wetlands not adjacent to navigable-in-fact waters, exceeding the plain meaning of the statute’s text, and prompting the observation: "In deciding whether to grant a permit, the [Corps] exercises the discretion of an enlightened despot, relying on such 12 13 3 The plurality concluded: "…the Corps jurisdiction over wetlands depends upon the existence of a significant nexus between the wetlands in question and navigable waters in the traditional sense. The required nexus must be assessed in terms of the statute’s goals and purposes…Accordingly, wetlands possess the requisite nexus, and thus come within the statutory phrase “navigable waters,” if the wetlands, either alone or in combination with similarly situated lands in the region, significantly affect the chemical, physical and biological integrity of other covered waters more readily understood as navigable. When in contrast, wetlands effects on water quality are speculative or insubstantial, they fall outside the zone fairly encompassed by the statutory term 'navigable waters.'" Op at 30. 514 U.S. 549 (1995). 33 C.F.R. § 320.4(a) (2004). Kirkpatrick & Lockhart Nicholson Graham LLP | JUNE 2006 When the Corps seeks to regulate wetlands adjacent to navigable-in-fact waters, it may rely upon adjacency to establish jurisdiction. Absent more specific regulations, however, the Corps must establish a significant nexus on a case-bycase basis when it seeks to regulate wetlands based on adjacency to non-navigable tributaries. Given the potential overbreadth of the Corps’ regulations, this showing is necessary to avoid unreasonable applications of the statute." Op. at 31. and Riverside Bayview decisions as establishing a “significant nexus” test that turns on the ecological significance of the wetlands in question. The dissenters would defer to the Corps’ interpretation and application of this term, which has, as was noted in various opinions, been inconsistent at best. ■ Future cases will likely turn on expert opinions concerning the nature of connections between wetland areas and navigable waters or their surface tributaries. Agency “expert” opinions addressing only hydrological connections between areas sought tobe regulated under the 404 program, and a “traditional” navigable water may no longer be sufficient to justify CWA jurisdiction. Similarly, agency opinions regarding the ecological significance of a minimal hydrological connection may also be insufficient to justify CWA jurisdiction. Landowners will still need to present expert testimony regarding the nature and tenuousness of such connections. ■ Entities seeking to challenge CWA permit decisions may have stronger legal and factual arguments to make. ■ EPA and the Corps must consider whether their regulations defining jurisdictional waters need to be reconsidered, especially in light of the concurring opinion by the Chief Justice, and especially if the Corps and EPA want lower courts to defer to their expertise. There will likely be much debate within the agencies regarding whether those regulations should reflect the plurality’s approach or that of Justice Kennedy. ■ Those decisions that had previously been described as representing the “majority” of case law – including Headwaters, Rueth, Deaton, and Needham – may no longer be controlling precedent in their respective circuits. ■ Although Rapanos focused on issues under section 404 of the CWA, the same basic analysis follows through the remainder of the statute, because the term “waters of the United States” defines the scope of not only dredge and fill permits, but also NPDES discharge permits and federal water quality standards. ■ Rapanos may well signal a renewed interest and vigor behind state regulatory programs. Although the scope of federal water quality regulation may be trimmed by Rapanos, state programs rest on different and often broader state constitutional Justice Kennedy concluded the lower courts did not apply that standard properly, stating: “[a]bsent some measure of the significance of the connection for downstream water quality, this standard [employed in Rapanos] was too uncertain…mere hydrological connection should not suffice in all cases.” Op. at 32. ■ The dissent (Justice Stevens, joined by Justices Souter, Ginsburg, and Breyer) concluded that the lower court decisions applied the right test – requiring a significant nexus – and properly deferred to the Corps’ expertise regarding what that means and whether it existed between the areas to be regulated and traditional navigable waters. WHAT DOES RAPANOS/CARABELL MEAN? The Court’s decision is interesting both for what is decided, and for the open questions left for future cases. The key points, we believe, are: ■ ■ 4 The Court narrowed the jurisdiction historically asserted by the Corps, holding that a mere hydrological connection is not sufficient to establish the “significant nexus” required for wetlands to be “waters of the United States,” and criticized the Corps’ regulations for their overbreadth. The split decision provides limited authoritative interpretation of CWA that will end these controversies. As pointed out by Chief Justice Roberts in his concurring opinion, no opinion commanded a majority of the Court on precisely how to read Congress’ limits on the reach of the CWA, leaving regulated entities and the courts to “feel their way on a case-by-case basis.” On the one hand, the plurality of justices read section 404 as applying only to wetlands with a “continuous surface connection to bodies that are ‘waters of the United States’ in their own right…” On the other hand, Justice Kennedy reads the SWANCC Kirkpatrick & Lockhart Nicholson Graham LLP | JUNE 2006 police powers and frequently broader statutory provisions. Thus, while the Corps and EPA may not be able to regulate wetlands and waters that are not directly or substantially connected to surface streams and rivers, state programs may well reach such wetlands and waters. Regulated entities may anticipate a renewed push for more vigorous enforcement of those state-level programs. At the same time, this decision contains analysis that touch upon issues ranging from federalism, to the deference due federal agencies, to the use of legislative history. All may be important not only to how the wetlands programs will be administered, but also to how the Court views these kinds of programs. Future alerts will address these wide-ranging issues. Barry M. Hartman bhartman@klng.com 202.778.9338 R. Timothy Weston tweston@klng.com 717.231.4504 John F. Spinello, Jr. jspinello@klng.com 973.848.4061 Morey Barnes, summer associate, contributed to this K&LNG Alert. If you have questions or would like more information about K&LNG’s Environmental Practice, please contact one of our lawyers listed below: BOSTON Michael DeMarco NEWARK 617.951.9111 mdemarco@klng.com William H. Hyatt, Jr. DALLAS NEW YORK Robert Everett Wolin 214.939.4909 rwolin@klng.com Donald W. Stever HARRISBURG PITTSBURGH R. Timothy Weston 717.231.4504 tweston@klng.com LOS ANGELES Frederick J. Ufkes 212.536.4861 dstever@klng.com 412.355.8612 rhosking@klng.com SAN FRANCISCO 310.552.5079 fufkes@klng.com Edward P. Sangster MIAMI Daniel A. Casey Richard W. Hosking 973.848.4045 whyatt@klng.com 415.249.1028 esangster@klng.com WASHINGTON 305.539.3324 dcasey@klng.com Barry M. Hartman 202.778.9338 bhartman@klng.com www.klng.com BOSTON • DALLAS • HARRISBURG • LONDON • LOS ANGELES • MIAMI • NEWARK • NEW YORK • PALO ALTO • PITTSBURGH • SAN FRANCISCO • WASHINGTON Kirkpatrick & Lockhart Nicholson Graham (K&LNG) has approximately 1,000 lawyers and represents entrepreneurs, growth and middle market companies, capital markets participants, and leading FORTUNE 100 and FTSE 100 global corporations nationally and internationally. K&LNG is a combination of two limited liability partnerships, each named Kirkpatrick & Lockhart Nicholson Graham LLP, one qualified in Delaware, U.S.A. and practicing from offices in Boston, Dallas, Harrisburg, Los Angeles, Miami, Newark, New York, Palo Alto, Pittsburgh, San Francisco and Washington and one incorporated in England practicing from the London office. This publication/newsletter is for informational purposes and does not contain or convey legal advice. The information herein should not be used or relied upon in regard to any particular facts or circumstances without first consulting a lawyer. Data Protection Act 1988—We may contact you from time to time with information on Kirkpatrick & Lockhart Nicholson Graham LLP seminars and with our regular newsletters, which may be of interest to you. We will not provide your details to any third parties. Please e-mail london@klng.com if you would prefer not to receive this information. © 2006 KIRKPATRICK & LOCKHART NICHOLSON GRAHAM LLP. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. Kirkpatrick & Lockhart Nicholson Graham LLP | JUNE 2006