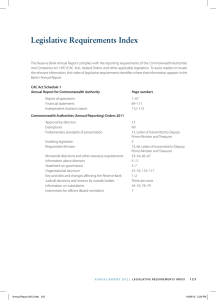

REGULATIONS, STATEMENTS OF POLICY, INTERPREATONS AND GUIDANCE DOCUMENTS:

advertisement