The Effectiveness of Limiting Alcohol Outlet Density Consumption and Alcohol-Related Harms

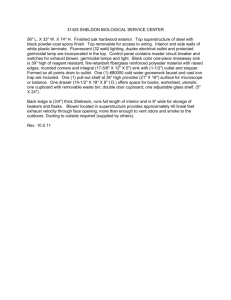

advertisement

Guide to Community Preventive Services The Effectiveness of Limiting Alcohol Outlet Density As a Means of Reducing Excessive Alcohol Consumption and Alcohol-Related Harms Carla Alexia Campbell, MHSc, Robert A. Hahn, PhD, MPH, Randy Elder, PhD, Robert Brewer, MD, MSPH, Sajal Chattopadhyay, PhD, Jonathan Fielding, MD, MPH, MBA, Timothy S. Naimi, MD, MPH, Traci Toomey, PhD, Briana Lawrence, MPH, Jennifer Cook Middleton, PhD, the Task Force on Community Preventive Services Abstract: The density of alcohol outlets in communities may be regulated to reduce excessive alcohol consumption and related harms. Studies directly assessing the control of outlet density as a means of controlling excessive alcohol consumption and related harms do not exist, but assessments of related phenomena are indicative. To assess the effects of outlet density on alcohol-related harms, primary evidence was used from interrupted time–series studies of outlet density; studies of the privatization of alcohol sales, alcohol bans, and changes in license arrangements—all of which affected outlet density. Most of the studies included in this review found that greater outlet density is associated with increased alcohol consumption and related harms, including medical harms, injury, crime, and violence. Primary evidence was supported by secondary evidence from correlational studies. The regulation of alcohol outlet density may be a useful public health tool for the reduction of excessive alcohol consumption and related harms. (Am J Prev Med 2009;37(6):556 –569) Published by Elsevier Inc. on behalf of American Journal of Preventive Medicine Introduction E xcessive alcohol consumption, including both binge drinking and heavy average daily alcohol consumption, is responsible for approximately 79,000 deaths per year in the U.S., making it the third-leading cause of preventable death in the nation.1 Approximately 29% of adult drinkers (ⱖ18 years) in the U.S. report binge drinking (five or more drinks on one or more occasions for men and four or more drinks for women) in the past 30 days, as do 67% of high school students who drink.2,3 The direct and indirect costs of excessive alcohol consumption in 1998 were $184.6 billion.4 The reduction of excessive alcohol consumption is thus a matter of major public health and economic interest. From the Community Guide Branch of the National Center for Health Marketing (Campbell, Hahn, Elder, Chattopadhyay, Lawrence, Middleton); National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (Brewer, Naimi), CDC, Atlanta, Georgia; Los Angeles County Department of Health Services (Fielding), Los Angeles, California; and University of Minnesota School of Public Health (Toomey), Minneapolis, Minnesota Address correspondence and reprint requests to: Robert A. Hahn, PhD, MPH, Community Guide Branch, Division of Health Communication and Marketing, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 4770 Buford Highway, Mailstop E-69, Atlanta GA 30333. E-mail: rhahn@cdc.gov. 556 The density of retail alcohol outlets is often regulated to reduce excessive alcohol consumption and related harms. Alcoholic beverage outlet density refers to the number of physical locations in which alcoholic beverages are available for purchase either per area or per population. An outlet is a setting in which alcohol may be sold legally for either on-premises or off-premises consumption. On-premises settings may include restaurants, bars, and ballparks; off-premises settings may include grocery and convenience stores as well as liquor stores. In 2005, the most recent year for which data are available, there were more than 600,000 licensed retail alcohol outlets in the U.S., or 2.7 outlets per 1000 population aged ⱖ18 years.5 The number of outlets per capita in states with state-owned retail outlets varied from a low of 0.48 per 1000 residents in Mississippi to a high of 7.25 per 1000 in Iowa.5 Alcohol outlet density is typically controlled by states. Under state jurisdiction, outlet density may be regulated at the local level through licensing and zoning regulations, including restrictions on the use and development of land.6 This regulation may be proactive as part of a community development plan, or in response to specific issues or concerns raised by community leaders. However, local control can be limited by state pre-emption laws, in which state governments explicitly or implicitly curtail the ability of local authorities to Am J Prev Med 2009;37(6) Published by Elsevier Inc. on behalf of American Journal of Preventive Medicine 0749-3797/09/$–see front matter doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2009.09.028 regulate outlet expansion.7 Thus, both state and local policies need to be considered when assessing factors that affect outlet density. The WHO has published a review that identifies outlet density control as an effective method for reducing alcohol-related harms.8 Similarly, in 1999, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration’s Center for Substance Abuse Prevention review concluded that there was a “medium” level of evidence supporting the use of outlet density control as a means of controlling alcohol-related harms.9 In addition, several organizations have advocated the use of outlet density regulation for the reduction of alcohol consumption and alcohol-related harms. These include the European Union (in their 2000 –2005 Alcohol Action Plan)10 and the WHO Western Pacific Region.11 The criteria used in the WHO report are not specified and may be expert opinion rather than systematic assessment of the characteristics of available studies. The SAMHSA review uses specified characteristics of included studies in drawing conclusions; however, the studies included are not up to date. In the present synthesis, 14 of the studies reviewed were published after 2000. Finally, a recent review by Livingston et al.12 presents useful conceptual hypotheses and notes the importance of outlet “bunching”—which the team referred to as “clustering”— density at a more micro level. Further, the present review assesses whether interventions limiting alcohol outlet density satisfy explicit criteria for intervention effectiveness of the Guide to Community Preventive Services (Community Guide), and assesses studies available as of November 2006. In addition, unlike any of the prior documents, the present review considers evidence from assessments of policies that are not explicitly considered densityrelated but that have direct effects on outlet density (i.e., privatization, liquor by the drink, and bans). If effective, policies limiting alcohol outlet density might address several national health objectives related to substance abuse prevention that are specified in Healthy People 2010.13 Guide to Community Preventive Services The systematic review described in this report represents the work of CDC staff and collaborators on behalf of the independent, nonfederal Task Force on Community Preventive Services (Task Force). The Task Force is developing the Community Guide with the support of the USDHHS in collaboration with public and private partners. The book The Guide to Community Preventive Services. What Works to Promote Health? presents the background and the methods used in developing the Community Guide.14 December 2009 Methods The methods of the Community Guide review process15,16 were used to assess whether the control of alcohol outlet density is an effective means of reducing excessive alcohol consumption and related harms. In brief, this process involves forming a systematic review development team (the team); developing a conceptual approach to organizing, grouping, and selecting interventions; selecting interventions to evaluate; searching for and retrieving available research evidence on the effects of those interventions; assessing the quality of and abstracting information from each study that meets inclusion criteria; drawing conclusions about the body of evidence of effectiveness; and translating the evidence on intervention effectiveness into recommendations. Evidence is collected on positive or negative effects of the intervention on other health and nonhealth outcomes. When an intervention is shown to be effective, information is also included about the applicability of evidence (i.e., the extent to which available effectiveness data might generalize to diverse population segments and settings), the economic impact of the intervention, and barriers to implementation. The results of this review process are then presented to the Task Force on Community Preventive Services (Task Force), an independent scientific review board from outside the federal government, which considers the evidence on intervention effectiveness and determines whether the evidence is sufficient to warrant a recommendation.15 Conceptual Approach and Analytic Framework Outlet density is hypothesized to affect excessive alcohol consumption and related harms by changing physical access to alcohol (i.e., either increasing or decreasing proximity to alcohol retailers), thus changing the distance that drinkers need to travel to obtain alcohol or to return home after drinking. Increases in the density of on-premises outlets can also alter social aggregation, which may adversely affect those who are or who have been drinking excessively, leading to aggressive or violent behavior (Figure 1). With alcoholic beverages acquired in off-premises settings, the consumption more often occurs at the purchaser’s home, and excessive consumption may be associated with domestic violence and suicidal behavior. Decreases in off-premises or on-premises alcohol outlets, or both, are expected to decrease access to alcoholic beverages by increasing the distance to alcohol outlets, increasing alcohol prices, reducing exposure to on-premises alcohol marketing, and potentially by changing social norms around drinking, thereby decreasing excessive alcohol consumption and related harms. Decreases in outlet density are expected to decrease social aggregation in and around on- and offpremises alcohol outlets which, in turn, may decrease aggressive behavior potentially exacerbated by alcohol consumption.17 Finally, decreased density increases distances traveled to and from alcohol outlets, thus increasing the potential for alcohol-related crashes. However, this potential harm could be mitigated by decreased alcohol consumption and hence decreased alcohol-impaired driving.18,19 Thus, the expected effect of outlet density on motor-vehicle crashes may be mixed.20 The effect that density has on consumption and harms may be further influenced by at least seven characteristics Am J Prev Med 2009;37(6) 557 Figure 1. Analytic framework showing the hypothesized effects of changes in outlet density on excessive alcohol consumption and related harms of retail alcohol outlets and the communities in which they are located: (1) outlet size (i.e., the physical size of the retail premises or the volume of its sales); (2) clustering (i.e., the level of aggregation of outlets within a given area); (3) location (i.e., the proximity of alcohol retail sites to places of concern, such as schools or places of worship); (4) neighboring environmental factors (e.g., demographics of the community and the degree of isolation of a community); (5) the size of the community (which may affect access to other retail sites); (6) the type and number of alcohol outlets (e.g., bar, restaurant, liquor store, grocery store) in a community may also influence whether and how outlet density affects drinking behavior21; and (7) alcohol outlets may be associated with illegal activities, such as drug abuse, which may also contribute to public health harms. As with other policies and regulations, the effects of regulations affecting outlet density may depend on the degree to which the policies are implemented and enforced. There are several challenges to directly evaluating the effectiveness of local policies in changing outlet density on alcohol consumption and related harms. Direct studies of the effects of policies changing density on alcohol-related public health outcomes have not been conducted. Policy changes may occur in small communities in which documentation and 558 data may be unavailable and where the number of retail alcohol outlets, alcohol-related outcomes, or both may be small; thereby it may be difficult to assess the relationship between outlet density and excessive alcohol consumption and related harms. Further, the effects of policy decisions on outlet density may be gradual. Other changes in alcohol control policies (e.g., enhanced enforcement of the minimum legal drinking age) may occur simultaneously, making it difficult to isolate the effect of changes in outlet density on drinking behavior. The team used both primary and secondary scientific evidence to help address these challenges and to comprehensively assess the impact of changes in alcohol outlet density on excessive alcohol consumption. Primary evidence included studies comparing alcohol-related outcomes before and after a density-related change. In this category were (1) studies assessing the impact of privatizing alcohol sales— commonly associated with increases in density; (2) studies assessing the impact of bans on alcohol sales—associated with decreases in density; and (3) studies of other alcohol licensing policies that directly affect outlet density (e.g., the sale of liquor by the drink). Time–series studies (i.e., studies in which the association between changes in outlet density and alcohol-related outcomes is assessed over time) were also used to provide primary evidence American Journal of Preventive Medicine, Volume 37, Number 6 www.ajpm-online.net of intervention effectiveness, even when the cause of the observed change in outlet density was unknown. The team did not include studies of strikes in the production or distribution of alcoholic beverages or studies of interventions among college populations. Secondary evidence included cross-sectional studies, which do not allow the inference of causality. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria To be included in this review, studies had to meet the following criteria: First, they had to evaluate changes in outlet density or policy changes that clearly resulted in changes in outlet density. Studies of policy changes (e.g., privatization or the legalization of liquor by the drink) had to provide evidence that there was a corresponding change in alcohol outlet density. Second, studies had to be conducted in high-income nations,a,22 be primary research (rather than a review of other research), and be published in English. Third, studies had to report outcome measures indicative of excessive alcohol consumption or related harms. Direct measures that had the strongest association with excessive alcohol consumption included binge drinking, heavy drinking, liver cirrhosis mortality, alcohol-related medical admissions, and alcohol-related motor-vehicle crashes, particularly singlevehicle nighttime crashes, which are widely used to indicate motor-vehicle crashes due to drinking and driving.23 Less direct measures included per capita ethanol consumption, which is a well-recognized proxy for the prevalence of heavy drinkers in a population8,24; unintentional injuries; suicide; and crime, such as homicide and aggravated assault. In most studies included in this review, consumption is measured by sales data; the team referred to this measure as “consumption” and note the exceptional study in which self-reported consumption is directly assessed. Fourth, studies had to be published in a peer-reviewed journal or in a government report. Reports not published or published by private organizations were not included. Search for Evidence The following databases were searched from inception up to November 2006 to identify studies assessing the impact of changes in alcohol outlet density and other review topics: EconLit, PsycINFO, Sociological Abstracts, MEDLINE, EMBASE, and EtOH (no longer available after 2003). The search yielded 6442 articles, books, and conference abstracts, of which 5645 were unique. After screening titles and abstracts, 251 papers and articles and 17 books were retrieved specifically related to outlet density; five articles could not be retrieved. After assessing quality of execution and design suitability (see below), 88 articles or books were included in the review. The actual number of studies that qualified for the a World Bank High-Income Economies (as of May 5, 2009): Andorra, Antigua and Barbuda, Aruba, Australia, Austria, the Bahamas, Bahrain, Barbados, Belgium, Bermuda, Brunei Darussalam, Canada, Cayman Islands, Channel Islands, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Denmark, Equatorial Guinea, Estonia, Faeroe Islands, Finland, France, French Polynesia, Germany, Greece, Greenland, Guam, Hong Kong (China), Hungary, Iceland, Ireland, Isle of Man, Israel, Italy, Japan, Republic of Korea, Kuwait, Liechtenstein, Luxembourg, Macao (China), Malta, Monaco, Netherlands, Netherlands Antilles, New Caledonia, New Zealand, Northern Mariana Islands, Norway, Oman, Portugal, Puerto Rico, Qatar, San Marino, Saudi Arabia, Singapore, Slovak Republic, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Trinidad and Tobago, United Arab Emirates, United Kingdom, U.S., Virgin Islands (U.S.) December 2009 review was less than this, however, because some studies were described in more than one report or publication. Assessing the Quality and Summarizing the Body of Evidence on Effectiveness Each study that met the inclusion criteria was read by two reviewers who used standardized review criteria (available at www.thecommunityguide.org/library/ajpm355_d.pdf) to assess the suitability of the study design and threats to validity. Uncertainties and disagreements between the reviewers were reconciled by the team. The classification of study design was based on Community Guide standards, and thus may differ from the classification reported in the original studies. Studies with greatest design suitability were those in which data on exposed and control populations were collected prospectively. Studies with moderate design suitability were those in which data were collected retrospectively or in which there were multiple pre- or post measurements but no concurrent comparison population. Studies with least-suitable designs were crosssectional studies or those in which there was no comparison population and only a single pre- and post-intervention measurement. On the basis of the number of threats to validity (maximum: nine; e.g., poor measurement of exposure or outcome, lack of control of potential confounders, or high attrition) studies were characterized as having good (one or fewer threats to validity); fair (two to four threats); or limited (five or more threats) quality of execution. Studies with good or fair quality of execution, and any level of design suitability (greatest, moderate, or least), qualified for the body of evidence synthesized in the review. The team summarized the results of cross-sectional studies based on whether drinking occurred on- or off-premises. However, some studies did not stratify their findings by outlet type and so were presented in a combined category. For each outcome and setting, the team summarized study findings by comparing the relative number of positive and negative findings. Finally, elasticities—summary effect measures showing the percentage change in an outcome per 1% change in an exposure (e.g., outlet density)—were calculated if the study provided sufficient information. Other Harms and Benefits, Applicability, Barriers, and Economics Harmful and beneficial outcomes not directly related to public health (e.g., vandalism or public nuisance) were noted if they were described in the studies reviewed or if the team regarded them as plausible. In addition, if an intervention was found to be effective, the team assessed barriers to implementation; the applicability of the intervention to other settings, populations, or circumstances; and the economic costs and benefits of the intervention. Results Intervention Effectiveness—Primary Evidence Time–series studies of alcohol outlet density change. The team found ten studies20,25–33 that directly evaluated the effect of changes in outlet density over time without identifying the causes for density changes. Of these, eight were “cross-sectional time–series” (i.e., panel) Am J Prev Med 2009;37(6) 559 studies of greatest design suitability20,25–29,31,33 and two were single-group time–series studies of moderate design suitability.30,32 Eight of the studies were of good execution25–31,33 and two were of fair execution.20,32 Few took spatial lag (i.e., the likelihood that neighboring geographic units are not statistically independent) into account. Five studies assessed associations between changes in outlet density and population-level alcohol consumption,25,26,28,31,33 and the remainder assessed specific alcohol-related harms.20,27,29,30,32 Consumption. All five studies that assessed the association between outlet density and population-level alcohol consumption found that they were positively associated; increased density was associated with increased consumption, and vice versa. Three studies examined the relationship between outlet density and the consumption of spirits in the U.S. The first study estimated that, from 1955 to 1980, for each additional outlet license per 1000 population, there was an increase of 0.027 gallons in per capita consumption of spirits ethanol (p⬍0.01).28 The second study reported an elasticity of 0.14 (p⬍0.01) for outlet density and spirits for the period 1970 –1975.31 The third study examined the association of outlet density and the sale of spirits and wine in 38 states over a period of 18 years; the effects of consumption on density were separated out by use of two-stage least squares regression. The elasticity for spirits and wine was found to be 0.033 (NS) and 0.015 (NS), respectively.26 A study assessing trends from 1952 to 1992 in the United Kingdom25 reported an elasticity of 2.43 (p⬍ 0.05) for off-premises density and beer consumption but no significant association for other beverages (except hard cider). Finally, a study33 examining data from 1968 to 1986 in Canada reported a significant association between reductions in off-premises density and reductions in alcohol consumption. This study also found an association between changes in outlet density and cirrhosis mortality, which was mediated by changes in alcohol consumption. When the alcohol consumption variable was added to the analytic model, the coefficient for cirrhosis mortality was no longer significant. Motor-vehicle crashes and other injury outcomes. Two studies by one author,20,30 using the same methods and database in California, found mixed results when evaluating the association between on- and off-premises outlet density and fatal and nonfatal motor-vehicle crashes in small California cities (i.e., with total populations ⬍50,000) during two different time periods and among different populations. The first study assessed the association between outlet density and crashes from 1981 through 1989 across all age groups. The author found a negative association between off-premises outlet density and both fatal and nonfatal crashes, and a 560 positive association between on-premises outlets and both fatal and nonfatal crashes.20 The second study assessed the association between outlet density and fatal and nonfatal crashes from 1981 through 1998 among people aged ⱖ60 years. This study reported a negative association for nonfatal crashes (elasticity: ⫺0.69, p⬍0.05) and a positive association for fatal crashes (elasticity: 1.18, p⬍0.05). Three studies27,29,32 assessed the relationship between outlet density and suicide or interpersonal violence. A study of young people aged 10 –24 years in the U.S. from 1976 through 1999 found positive associations between outlet density (on- and off-premises outlets combined) and suicides for most gender and age strata assessed, but only the findings for boys/men aged 15–19 years were significant (elasticities ranged from ⫺0.03 to 0.10 for girls/women and from 0.05 to 0.12 for boys/men).29 The effect of changes in the density of on-premises outlets and violent crime was investigated in Norway from 1960 through 1995.32 The researcher used autoregressive integrated moving average (ARIMA) modeling and found that each alcohol outlet was associated with 0.9 violent crimes investigated (by the police) per year. A supplementary analysis found that this association persisted even after controlling for amount of alcohol consumption, suggesting that the effect of increased density was independent of the effect of increased alcohol consumption (p⬍0.03). This suggests that the social aggregation of drinkers in and around alcohol outlets directly affects assaults, as indicated in Figure 1 (under “social problems”). Finally, a study of 581 California neighborhoods identified by ZIP code from 1996 through 200227 indicated that an increase in on- and off-premises outlet density was associated with an increase in hospitalizations for assault, but that this association varied for on-premises and off-premises locations, and among various types of on-premises locations (e.g., bar or restaurant) as well. The researchers used random-effects regression models, taking spatial lag into account, thus allowing for the lack of independence of neighborhoods in the association of outlets and alcohol-related harms. Within a given ZIP code, the elasticity for off-premises outlets and alcohol-related assaults on residents was 0.167 (p⬍0.001); for restaurants, it was ⫺0.074 (p⬍0.01); and for bars, 0.064 (p⬍0.001). The elasticity for bars and assaults involving residents of neighboring ZIP codes was also significant (0.142, p⬍0.001); however, the elasticities for off-premises alcohol outlets and for restaurants relative to assaults involving residents of neighboring ZIP codes were not significant. Based on these results, the authors estimated that, on average, eliminating one bar per ZIP code in California would reduce the number of assaults requiring overnight hospitalization by 290 per year in the state. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, Volume 37, Number 6 www.ajpm-online.net Summary Seven of nine time–series studies found positive associations between changes in outlet density and alcohol consumption and related harms, particularly interpersonal violence. However, two studies assessing the relationship between alcohol outlet density and motorvehicle crashes in small California cities during two different time periods20,30 had inconsistent findings for which no clear explanation was apparent. The studies reviewed also suggested that the association between outlet density and interpersonal violence may at least partially be due to social aggregation in and around alcohol outlets, and that the density of outlets in a given locale can also influence the probability of assaults involving residents of neighboring communities. Privatization Studies Alcohol privatization involves the elimination of government monopolies for off-premises alcohol sales to allow sales by privately owned enterprises. In the U.S. and Canada, privatization occurs at the state or provincial level; in many European nations, privatization may occur at a national level, currently guided by policies of the European Union. In the U.S., one alcoholic beverage may be privatized at a time; for example, wine might be privatized (i.e., subsequently for sale in commercial settings) while spirits may not be privatized, or may be privatized at a different time. Typically, privatization results not only in a substantial increase in the number of outlets where alcohol can be purchased but also in changes in alcohol price, days and hours of sale, and marketing.21,34 This combination of events limits the ability to attribute subsequent changes in alcohol consumption and related harms to changes in outlet density alone. Nonetheless, because of the impact privatization generally has on outlet density, the team concluded that privatization studies were relevant for assessing the impact of changes in outlet density on excessive alcohol consumption and related harms. The effects of privatization on the privatized beverages are assessed first, followed by an assessment of the effects of privatization on beverages other than those for which sales were privatized. If privatization affects consumption and related harms by means of increased outlet density, the consumption (and related harms) of the privatized beverage should increase, while consumption of other beverages might decline if usual drinkers of these other beverages now switch to the newly available privatized beverage. Comparing the association between alcohol consumption and alcoholrelated harms associated with privatized and nonprivatized alcoholic beverages, respectively, provides a basis for assessing the impact of privatization on alcohol consumption and related harms while controlling for other factors that might be occurring simultaneously. December 2009 Following an analysis of the effects of privatization, this section then reviews the effects of remonopolization, that is, reversing privatization by reinstatement of government monopoly control over the retail sales of alcohol beverages. This policy change would be expected to have the opposite effects of privatization and result in lower alcohol outlet density. Eleven events of privatization and one of remonopolization, analyzed in 17 studies and reported in 12 papers,35– 45 met the review inclusion criteria. The units of analysis were eight U.S. states (AL, ID, IA, ME, MT, NH, WA, WV); two Canadian provinces (Quebec and Alberta); and (in the sole study of remonopolization) Sweden. Several studies assessed overlapping privatization events. For example, two research teams assessed the privatization of wine and then spirits in Iowa,34,38,39,45 and two researchers assessed early phases of the privatization of wine in Quebec, while one of these researchers also assessed the later phases, with each phase counted as a separate privatization event.36,46 In addition, several papers assessed the effects of privatization in more than one state and provided separate effect estimates for the privatization in each state; for purposes of this review, each state-level assessment was treated as a separate study. Finally, a single state or province could privatize different beverages at different times, resulting in separate privatization events. Altogether, the events assessed in these studies occurred between 1978 and 1993. In all areas assessed, the number of outlets increased dramatically following privatization. The studies used ARIMA time–series study design; all except two studies36,46 reported results for comparison populations. All studies used alcohol sales data as a measure of population-level alcohol consumption. One study also assessed fatal motor-vehicle crashes (MVCs),42 another study34 also evaluated single-vehicle nighttime crashes and liver cirrhosis. The single study of remonopolization40 assessed hospitalizations for alcoholism, alcohol intoxication, and alcohol psychosis combined, alcohol intoxication alone, assaults, suicides, falls, and MVCs.40 Fourteen studies (in seven papers)35,38,39,42– 44,46 were of greatest design suitability; three studies (in two papers)37,40 were of moderate design suitability. All studies were of fair execution. Effects of Privatization on Privatized Beverages Seventeen studies35– 44 assessed the effects of privatization on the sale of at least one of four beverage types (wine, spirits, full-strength beer, and medium-strength beer) in ten settings. The median relative increase in alcohol sales subsequent to privatization was 42.0%, with an interquartile interval of 0.7% to 136.7%. That is, among the studies reviewed, compared with consumption prior to privatization, the median effect was Am J Prev Med 2009;37(6) 561 an increase of 42.0% in consumption of the privatized alcoholic beverage. Studies of three events of privatization, two in Iowa and one in Alberta, yielded inconsistent findings, which merit further description. In Iowa, wine was privatized in 1985, and spirits in 1987. Wagenaar and Holder35,43 reported that wine consumption increased 93.0% (95% CI⫽69.3, 120.2) from baseline to 44 months after privatization of retail wine sales. Following the subsequent privatization of retail spirits sales in Iowa 2 years later, these researchers35,43 reported a 9.5% (95% CI⫽3.5, 15.9) increase in spirits consumption; they also found no evidence that privatization affected cross-border alcohol purchasing.35,43 In contrast, Mulford and Fitzgerald39 found that wine privatization in Iowa was associated with a nonsignificant increase of only 0.5% (95% CI⫽ ⫺13.2, 16.4) in wine sales, and that spirits privatization was associated with a nonsignificant increase of 0.7% (95% CI⫽ ⫺4.3, 6.0) in spirits sales. Differences between the findings of these research groups may be due to differences in time periods assessed, modeling variables and procedures, beverage types included in the assessment (e.g., Mulford and Fitzgerald exclude wine coolers that were not affected by the policy change and Wagenaar and Holder do not), use of a control population, and outcome measurement. Fitzgerald and Mulford34 also report small unadjusted rate decreases in single-vehicle nighttime crashes (⫺1.6%) and alcoholic cirrhosis mortality (⫺5.5%) associated with the privatization of wine and spirits in Iowa. A study in Alberta, Canada, estimated that gradual privatization over a period of 20 years resulted in an increase in spirits consumption of 12.7% (95% CI⫽2.2, 24.4) and no change in either wine or beer consumption.42 Although the process of privatization occurred over an extended period, the major events of privatization occurred essentially at the same time (in 1992); thus, considered in aggregate, privatizing spirits in Alberta increased total alcohol sales by 5.1% (95% CI⫽ ⫺2.8, 13.7) over this 20-year period. Despite the increased alcohol sales, the authors reported that there was an estimated 11.3% (95% CI⫽ ⫺33.8, 19.0) decrease in traffic fatalities. However, neither the increase in total alcohol sales nor the decrease in traffic fatalities was significant. Effects of Privatization on Beverages Not Subject to Privatization Five publications37,38,43,44,47 assessed the effects of privatization in eight settings on the concomitant sales of alcoholic beverages that were not privatized during the same period. Overall, these studies reported that there was a minimal decline: a median of 2.1% (interquartile interveral [IQI]: ⫺4.8% to 2.7%) in the sales on nonprivatized beverages. 562 Effects of Remonopolization on Alcohol-Related Outcomes A single before-and-after study40 evaluated the effects of remonopolization of sales of medium-strength beer in Sweden. This study compared the association between the number of retail alcohol outlets and the occurrence of six different alcohol-related outcomes during a 51-month period following the remonopolization of medium-strength beer, with that for a similar period prior to remonopolization. Among young people aged 10 –19 years, alcoholism, alcohol intoxication, and alcohol psychosis (which were considered in combination) decreased by 20% (p⬍0.05) following remonopolization. These outcomes also decreased by ⬎5% among people aged ⱖ40 years, although the change was not significant (p⬎0.05). Hospitalizations for acute alcohol intoxication also decreased between 3.5% and 14.7% (p⬎0.05); suicides decreased by 1.7% to 11.8% (p⬎0.05); and falls decreased by 3.6% to 4.9% (p⬎ 0.05) following remonopolization, although none of these changes were significant either. Motor-vehicle crashes (MVCs) significantly decreased by 14% (p⬍ 0.05) in all age categories except one (those aged 20 –39 years). Other nonsignificant changes include assaults, which decreased by 1.4% among those aged 20 –39 years, but increased by 6.9% to 14.8% (p⬎0.05) in the other age groups: 10 –19, 40 –59, ⱖ60 years. The authors did not provide any explanation for this seemingly inconsistent finding. Summary These studies indicate that privatization increases the sales of privatized beverages but has little effect on the sales of nonprivatized alcoholic beverages. The one study that evaluated the reintroduction of government monopoly control of sale of an alcoholic beverage (medium-strength beer) found that remonopolization led to a significant decrease in motor-vehicle crashes for most age groups and a significant decrease among youth for several, but not all, alcohol-related harms. Studies of Alcohol Bans The team found seven studies18,41,48 –52 that examined the effects of bans on local on- or off-premises alcohol sales or consumption (i.e., “dry” towns, counties, or reservations). Five studies examined the effects of bans in American Indian and Native settings in Alaska,49,50,53 northern Canada,52 and the southwestern U.S.51 Two studies assessed the effects of bans in nontribal areas of the U.S. and Canada.18,41 Two studies were of greatest design suitability18,41; two of moderate design suitability50,51; and three of least suitable design.49,52,53 All were of fair execution. The studies examined events that occurred from 1970 American Journal of Preventive Medicine, Volume 37, Number 6 www.ajpm-online.net through 1996. Two additional studies modeled the association of multiple policies, including local policies of dry counties, with spirits consumption28 and with juvenile suicide.29 Both of these studies were of greatest design suitability and good execution, and the team considered them comparable to studies of bans and as primary evidence. An additional cross-sectional study of bans54 was not used as primary evidence of effectiveness, but provided insights into the effect that alcohol availability in areas surrounding dry communities (e.g., outside Indian reservations) has on the occurrence of alcohol-related harms among residents of the dry communities. ban alcohol in 1978. Although comparative data are not available from this study (and the study thus does not meet review inclusion criteria), it is notable that during the 3 years following the implementation of this prohibition there were only five arrests for the illegal possession of alcohol and, of these, four were associated with a single incident. The reported reduction in alcohol consumption in general and among youth in particular was linked with several societal benefits, including improved mental and physical health among community members, and a reduction in conflicts within the community. The ban on alcohol sales was associated with a reduction in the use of other substances of abuse (e.g., inhalants) by youth. Effects of Alcohol Bans in Isolated Communities All of the studies that evaluated the effect of bans in isolated northern communities found substantial reductions in alcohol-related harms with the exception of suicide.18,41,49,51–59 In the communities that instituted bans, rates of harm indicated by alcohol-related medical visits were reduced by 9.0% for injury deaths to 82% for alcohol-related medical visits (CIs not calculable). One of these studies50 found that the effects were reversed when the ban was lifted, and found similar benefits when the ban was then reimposed (Figure 2).50 Two of these studies suggest that bans on alcohol sales in isolated communities led residents to decrease their use of other intoxicants. In Barrow, Alaska, medical visits for use of isopropyl alcohol declined during ban periods.50 An additional study qualitatively evaluated a Canadian Inuit community52 that overwhelmingly voted to Effects of Alcohol Bans in Less-Isolated Communities Monthly average number of visits per period Studies assessing the impact of bans (particularly bans on on-premises sales) in less-isolated communities have produced mixed results. Some studies have found that bans are associated with increases in alcohol-related harms, including motor-vehicle crashes18,46 and alcohol-related arrests.51 However, two studies28,29 found that states that had a larger proportion of their population living in dry counties had less alcohol consumption and related harms than states that had a smaller proportion of their population living in dry counties. One study28 found that living in dry counties was associated with lower rates of spirits consumption (p⬍0.01). The other study found small, nonsignificant associations with male suicide (elasticities of ⫺0.002 to ⫺0.066) and female suicide (elasticities of ⫺0.021 to ⫺0.038).29 A cross-sectional study of injury deaths in New Mexico54 highlights the poten100 tial harms associated with al90 cohol sales bans in areas (in Total this case reservations, 80% of 80 Withdrawal which are dry) that are adjaMedical/GI 70 cent to other areas where alTrauma cohol is readily available. 60 Acute intoxication/ This study found that in detoxification these settings, although the 50 Suicide attempt relative risk (RR) of total in40 jury deaths was greater for Family violence American Indians than for Exposure 30 whites (RR⫽3.1; 95% CI⫽2.6, Isopropyl 20 3.6), the relative risk was greatPregnancy est for deaths involving pedes10 trians struck by vehicles (RR⫽7.5; 95% CI⫽5.3, 10.6) 0 and for hypothermia (i.e., No Ban 1 Ban 1 No Ban 2 Ban 2 (Nov 93–Oct 94) (Nov 94–Oct 95) (Nov 95–Feb 96) (Mar 96–Jul 96) freezing to death; RR⫽30.5; 95% CI⫽17.7, 48.7). FurtherBan periods more, American Indians in New Mexico who died of Figure 2. Alcohol-related outpatient visits associated with changes in alcohol ban policy, these causes were likely to Barrow, Alaska, 1993–199650 December 2009 Am J Prev Med 2009;37(6) 563 have elevated blood alcohol levels (an average of 0.24 g/dL and 0.18 g/dL for pedestrian deaths and hypothermia, respectively). A disproportionate number (67%) of these deaths occurred in counties bordering reservations, despite the fact that most American Indians live on reservations. Although the design of this study does not allow causal inference regarding the effect of bans, these findings suggest that travel between dry reservations and adjacent areas where alcohol is readily available may increase the risk of death from these external causes among those traveling offreservation to purchase alcohol. Summary The effectiveness of bans in reducing alcohol-related harms appears to be highly dependent on the availability of alcohol in the surrounding area. In isolated communities, bans can substantially reduce alcoholrelated harms. However, where alcohol is available in areas nearby those with bans, travel between these areas may lead to serious harms. Studies of Licensing-Policy Changes Affecting Outlet Density The team identified four studies of national or local licensing-policy changes that resulted in increased outlet density. The studies were conducted in Iceland,60 Finland,47 New Zealand,61 and North Carolina.62 The policy changes assessed occurred between 1969 and 1990. The North Carolina study was of greatest design suitability and good execution. The other three studies were of moderate design suitability and good execution.47,60,61 These studies examined various indices of alcohol consumption; the North Carolina study also assessed effects on alcohol-related motor-vehicle crashes. Another study assessed the effect of a change in national policy controlling the sale of table wine in New Zealand. Effects on Excessive Alcohol Consumption and Related Harms The only U.S. study that met criteria for this category of interventions evaluated the decision by several North Carolina counties to allow on-premises sale of spirits (i.e., “liquor by the drink” [LBD]), replacing the previous option of “brown-bagging,”62 in which patrons of an establishment bring their own alcoholic beverage (in a bag) and the establishment supplies other items (e.g., a drink glass, ice, water). Of the 100 counties in North Carolina, three approved liquor by the drink in November 1978 and eight approved it in January 1979. The policy change was followed by the opening of many bars and lounges adjacent to restaurants. Interrupted time–series models indicated that, relative to counties that did not change their policies, sales of spirits increased in LBD counties by 8.2% (p⬍0.05) among 564 the first group of counties to adopt the new policy, and by 4.3% (p⬍0.05) among the second group. Nighttime single-vehicle crashes among men of legal drinking age also increased in both early- and late-adopting counties by 18.5% (p⬍0.01) and 15.7% (p⬍0.01), respectively. However, there were no significant changes in rates of nighttime single-vehicle crashes among boys/men aged ⬍21 years, who were not permitted to drink spirits and were thus not (legally) affected by the policy change. In Finland, the enactment in 1969 of a policy allowing the sale of medium-strength beer resulted in a 22% increase in the number of monopoly alcohol outlets and a 46% increase in restaurant liquor licenses, and permitted 17,400 grocery stores to sell mediumstrength beer. During the year following these changes, overall alcohol sales in Finland increased by 46%. Of the increase, 86% was attributed by the researchers to the increased availability of beer. Overall alcohol consumption increased by 56%, with the greatest volume increases among those drinking more than a half liter of pure alcohol per year (1/2 liter of pure alcohol is equivalent to 1/3 gallon of 80-proof liquor). However, alcohol consumption increased significantly among all adults at all levels of alcohol consumption in Finland subsequent to this policy change, regardless of their baseline pattern of consumption, including those who had previously reported that they had not consumed alcohol during the past year. In Iceland,60 a policy change in 1989 resulted in an expansion in off-premises monopoly outlets and commercial on-premises outlets in Reykjavik and in rural areas. Over the subsequent 4-year period, consumption increased by 43% among men who drank more than 350 centiliters of alcohol per year at baseline, but changed minimally among women and men who drank at lower levels. In New Zealand,61 a policy change in 1989 allowed the sale of table wine in grocery stores, resulting in an increase of approximately 25% in the number of wine outlets in the country over a 2-year period. This resulted in a 17% (95% CI⫽9.8%, 24.9%) increase in wine sales during this time, but in no change in the sales of other alcoholic beverages. This indicates that there was an overall increase in alcohol consumption in New Zealand subsequent to this policy change, and that wine, the privatized beverage, was not being substituted for other nonprivatized alcoholic beverages. Summary These studies consistently indicated that more permissive licensing procedures increased the number of onand off-premises alcohol outlets, which in turn led to increases in alcohol consumption. Two of these studies specifically reported increases in alcohol consumption among heavy drinkers, and one study reported an increase in drinking among survey subjects who reported not drinking during a specified period at the American Journal of Preventive Medicine, Volume 37, Number 6 www.ajpm-online.net baseline assessment. The single study that evaluated alcohol-related harms (alcohol-related motor-vehicle crashes) found that they increased substantially after allowing the sale of liquor by the drink. Intervention Effectiveness—Secondary Evidence Although the primary evidence just reviewed is heterogeneous in topic and design and does not allow summary tabular presentation, the secondary evidence presented below is based on consistent statistical procedures and readily allows a summary table. Cross-Sectional Studies Findings from studies of on- and off-premises outlets combined. The 28 cross-sectional studies19,55–57,63– 86 that assessed the association of outlet density (onpremise and off-premise, not distinguished) assessed 47 alcohol-related outcomes. Of these outcomes, 41 (87.2%) found a positive association, that is, as density increased, so did consumption and alcohol-related harms, and vice versa (Table 1, A). Positive associations were found for consumption-related outcomes (e.g., per capita alcohol consumption); violence and injury outcomes; and several medical conditions (e.g., liver disease). The mean elasticities ranged from 0.045 for crime to 0.421 for motor-vehicle crashes. Findings from studies of on-premises outlets. The 23 studies23,58,78,79,87–105 that assessed the association of outlet density and alcohol-related outcomes in onpremises outlets reported on 25 outcomes. Of these, 21 (84.0%) indicated a positive association (Table 1, B). Positive associations were also found for consumptionrelated outcomes, several forms of violence and injury outcomes related to alcohol consumption, and one medical condition. Mean study elasticities could be estimated for most outcome types, and values ranged from 0.021 for child abuse to 0.250 for population consumption. Findings from studies of off-premises outlets. The 23 studies58,79,89 –92,94 –99,101–111 that assessed the association of outlet density and alcohol-related outcomes in off-premises outlets reported on 24 outcomes. Of these, 18 (75.0%) also indicated a positive association (Table 1, C). Positive associations were found for consumption-related outcomes, several forms of violence and injury outcomes related to alcohol consumption, and one medical condition. Mean study elasticities could be estimated for most outcome types and values ranged from ⫺0.15 for injury to 2.46 for population consumption. Mean elasticity was also high (0.483) for violent crime. Summary Cross-sectional studies generally show consistent positive associations between alcohol outlet density and December 2009 Table 1. Cross-sectional studies, outcomes by setting type # of studies Outcomes A. ON- AND OFF-PREMISES Consumption Population consumption Binge drinking Underage drinking Violence and injury Violent crime Injury Motor-vehicle crashes Drunk driving Crime Medical conditions Alcohol medical visits Alcoholism Liver disease Total all premises B. ON-PREMISES Consumption Population consumption Binge drinking Violence and injury Violent crime Injury Motor-vehicle crashes Drunk driving Crime Child abuse Medical conditions Liver disease Total on-premises C. OFF-PREMISES Consumption Population consumption Binge drinking Violence and injury Violent crime Injury Motor-vehicle crashes Drunk driving Crime Child abuse Medical conditions Liver disease Total off-premises % positive M elasticity AGGREGATED 7 5 2 85.7 80.0 100.0 0.27 15 3 6 1 2 93.3 100.0 50.0 100.0 100.0 0.32 0.23 0.42 1 1 4 47 100.0 100.0 100.0 87.2 3 1 33.3 100.0 0.25 4 3 6 2 1 2 100.0 100.0 66.7 100.0 100.0 100.0 0.12 0.14 0.05 3 25 100.0 84.0 0.06 2 1 100.0 100.0 2.46 6 3 5 2 1 2 100.0 66.7 80.0 50.0 100.0 100.0 0.48 ⫺0.15 0.10 2 24 50.0 76.9 ⫺0.05 0.04 0.02 0.01 excessive alcohol consumption and related harms, with the possible exception of injuries, for which the findings were less consistent. The largest effect sizes were for studies relating outlet density to population consumption and violent crime. Summary of the Body of Scientific Evidence on Alcohol Outlet Density and Excessive Drinking and Related Harms Using a variety of different study methods, study populations, and alcohol measures, most of the studies included in this review reported that greater outlet Am J Prev Med 2009;37(6) 565 density is associated with increased alcohol consumption and related harms, including medical harms, injuries, crime, and violence. This convergent evidence comes both from studies that directly evaluated outlet density (or changes in outlet density) and those that evaluated the effects of policy changes that had a substantial impact on outlet density, including studies of privatization, remonopolization, bans on alcohol sales and the removal of bans, and changes in density from known policy interventions and from unknown causes. Studies assessing the relationship between alcohol outlet density and motor-vehicle crashes produced mixed results.18,20,62,112 Other Benefits and Harms Communities commonly seek limits on alcohol outlet density, either through licensing or zoning, for purposes that may not be directly related to public health (e.g., the reduction of public nuisance, loitering, vandalism, and prostitution).7,113 Although the team did not specifically search for studies that assessed these outcomes, some of the studies the team reviewed suggested that there may be an association between outlet density and these outcomes as well. For example, a study from New South Wales, Australia, reported an association between outlet density and “neighborhood problems with drunkenness” but did not find a significant association with property damage.114 There was evidence of one potential harm of decreased outlet density (i.e., an increase in fatal single-vehicle nighttime vehicle crashes) presumably associated with an increase in driving in response to greater distances between alcohol outlets.19 Applicability Evidence of the association of outlet density and alcohol consumption and related harms derives from studies conducted primarily in North American and in Scandinavian countries. One study27 indicated that the impact of changes in outlet density may be affected by demographic characteristics (e.g., gender distribution) of the population; in this case, the association of outlet density with assaults requiring hospitalization was stronger where there was a greater proportion of boys/men in the population. Most of the studies reviewed assessed the effects of increased outlet density, which is a consequence of the general trend toward liberalization of alcohol policies associated with outlet density. Few data were found from which to draw inferences about regulations that control or reduce outlet density. Studies of bans on alcohol sales, conducted primarily among American Indian and Alaska Native populations, consistently report a reduction in excessive consumption and related harms following the implementation of a ban on alcohol sales, possession, or both, 566 provided the area affected by the ban was not surrounded by other sources of alcoholic beverages. Barriers Reductions in outlet density, with resultant reductions in consumption, are likely to have substantial commercial and fiscal consequences, and thus may be opposed by commercial interests in the manufacture, distribution, and sale of alcoholic beverages. In keeping with its commercial interests, the alcoholic beverage industry has tended to support policies that facilitate outlet expansion.115 State pre-emption laws (i.e., laws that prevent implementation and enforcement of local restrictions) can also undermine efforts by local governments to regulate alcohol outlet density.7 Indeed, the elimination of pre-emption laws related to the sale of tobacco products is one of the health promotion objectives in Healthy People 2010.13 However, there is no similar objective in Healthy People 2010 related to the sale of alcoholic beverages. Economic Evaluation The team’s systematic economic review did not identify any study that examined the costs and benefits of limiting alcohol outlet density. Although there has been speculation that reducing the number of alcohol outlets may result in a loss of revenue to state and local governments owing to a loss of licensing fees and alcohol tax revenues, the team found no studies that have documented this speculation. In addition, there may be economic gains resulting from revenue generation from merchants and consumers who would otherwise avoid areas known to have a high alcohol outlet density; however, the team found no studies about this topic. Moreover, in 2006, alcoholic beverage licenses accounted for only $406 million (0.9%) of the $45 billion that state governments received from all licensing fees, and alcohol taxes accounted for only 0.7% of all taxes ($4.9 billion of $706 billion) collected by state govern ments (www.census.gov//govs/statetax/0600usstax. html). Even in the absence of published data on program implementation costs and other costs related to this intervention, it should be expected that the cost of restricting access to alcohol by limiting the number of alcohol outlets is likely to be small relative to the societal cost of excessive alcohol consumption in the U.S. For example, in 1998, the most recent year for which data are available, the societal cost of excessive alcohol consumption in the U.S. was $185 billion, including, among other costs, approximately $87 billion in lost productivity due to morbidity, $36 billion in lost future earnings due to premature deaths, $19 billion in medical care costs, $10 billion in lost earnings due to crime, $6 billion in costs to the criminal justice American Journal of Preventive Medicine, Volume 37, Number 6 www.ajpm-online.net system, and $16 billion in property damage related to motor-vehicle crashes.4 Moreover, each state alcohol enforcement agent is responsible for monitoring an average of 268 licensed establishments116; thus, reducing the number of retail alcohol outlets might reduce their enforcement responsibilities. In summary, no existing study examines the economic costs and benefits of limiting alcohol outlet density. Research Gaps Although the scientific evidence reviewed indicates that the regulation of alcohol outlet density can be an effective means of controlling excessive alcohol consumption and related harms, it would be useful to conduct additional research to further assess this relationship: ● ● ● ● ● There are few if any studies evaluating how local decisions are made regarding policies affecting alcoholic beverage outlet density or the consequences of such policy changes. Such case studies may be difficult to conduct, but they could provide important insights to guide policy decisions regarding alcohol outlet density in other communities. The majority of outlet density research explores the impact of increasing alcohol outlet density on alcoholrelated outcomes; there is a lack of research on the impact of reducing outlet density. This might be done by observing the impact of temporal changes in outlet density on excessive alcohol consumption and related harms. The association of on- and off-premises alcoholic beverage outlets with illegal activities such as prostitution and drug abuse should be examined. In themselves, these may have adverse public health and other outcomes; in addition, they may confound the apparent association of alcohol outlets with these outcomes. Relatively little is known about the impact of density changes relative to baseline density levels. Some authors (e.g., Mann117) have proposed that the association between outlet density and alcohol consumption follows a demand curve, such that when density is relatively low, increases in density may be expected to have large effects on consumption, and when density is relatively high, increases in density should be expected to have smaller effects.21,117 Thus, it would be useful to assess this hypothesis empirically using econometric methods, with different kinds of alcohol-related outcomes. Such information would allow communities at different alcohol outlet density “levels” to project the possible benefits of reducing density by specific amounts or the potential harms of increasing density. For public health practitioners, legislators, and others attempting to control alcohol outlet density to reduce alcohol-related harms, it would be useful to December 2009 ● catalog approaches to regulation beyond licensing and zoning that may have an effect on outlet density (e.g., traffic or parking regulations that, in effect, control the number of driving patrons who may patronize an alcohol outlet). A primary rationale for limiting alcohol outlet density is to improve public health and safety. Furthermore, the economic efficiency of limiting outlet density is difficult to assess without data on the economic impact of this intervention. To remedy this, future studies on the impact of changes in alcohol outlet density should assess both health and economic outcomes, so that the economic impact of this intervention can be assessed empirically. The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the CDC. The authors are grateful for the contributions of Ralph Hingson, ScD, MPH (National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism), and Steve Wing (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services). No financial disclosures were reported by the authors of this paper. References 1. CDC. Alcohol-attributable deaths and years of potential life lost—United States, 2001. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2004;53(37):866 –70. 2. Miller JW, Naimi TS, Brewer RD, Jones SE. Binge drinking and associated health risk behaviors among high school students. Pediatrics 2007; 119(1):76 – 85. 3. National Center for Health Statistics. Health, United States, 2005 with chartbook on trends in the health of America. Hyattsville MD: National Center for Health Statistics, 2005. USDHHS No. 2005–1232. 4. Harwood H. Updating estimates of the economic costs of alcohol abuse in the United States: estimates, update methods, and data. Rockville MD: National Institute on alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, 2000. NIH Publication No. 98-4327. 5. National Alcoholic Beverage Control Association. NABCA survey book. Alexandria VA: NABCA, 2005. 6. Ashe M, Jernigan D, Kline R, Galaz R. Land use planning and the control of alcohol, tobacco, firearms, and fast food restaurants. Am J Public Health 2003;93(9):1404 – 8. 7. Mosher J. Alcohol issues policy briefing paper: the perils of preemption. Chicago IL: American Medical Association, 2001. 8. Babor TF, Caetano R, Casswell S, et al. Alcohol: no ordinary commodity— research and public policy. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003. 9. Grover PL, Bozzo R. Preventing problems related to alcohol availability: environmental approaches. Rockville MD: SAMHSA/CSAP, 1999. DHHS Publication No. (SMA) 99-3298. 10. WHO. European Alcohol Action Plan, 2000 –2005. Copenhagen: WHO, 2000. 11. WHO. Draft regional strategy to reduce alcohol-related harm. Auckland, New Zealand: WHO, 2006. 12. Livingston M, Chikritzhs T, Room R. Changing the density of alcohol outlets to reduce alcohol-related problems. Drug Alcohol Rev 2007;26:557– 66. 13. USDHHS. Healthy People 2010. Washington DC: USDHHS, 2001. 14. Task Force on Community Preventive Services. The Guide to Community Preventive Services. What works to promote health? In: Zaza S, Briss PA, Harris KW, eds. New York: Oxford University Press, 2005. www.thecommunityguide.org. 15. Briss PA, Zaza S, Pappaioanou M, et al. Developing an evidence-based Guide to Community Preventive Services—methods. Am J Prev Med 2000;18(1):35– 43. Am J Prev Med 2009;37(6) 567 16. Zaza S, Wright-De Aguero LK, Briss PA, et al. Data collection instrument and procedure for systematic reviews in the Guide to Community Preventive Services. Am J Prev Med 2000;18(1):44 –74. 17. Lipsey MW, Wilson DB, Cohen MA, Derzon JH. Is there a causal relationship between alcohol use and violence? In: Galanter M, ed. Recent developments in alcoholism. Vol. XIII. Alcohol and violence. New York: Plenum Press, 1997:245– 82. 18. Baughman R, Conlin M, Dickert-Conlin S, Pepper J. Slippery when wet: the effects of local alcohol access laws on highway safety. J Health Econ 2001;20(6):1089 –96. 19. Gruenewald PJ, Treno AJ, Nephew TM, Ponicki WR. Routine activities and alcohol use: constraints on outlet utilization. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 1995;19(1):44 –53. 20. McCarthy P. Alcohol-related crashes and alcohol availability in grass-roots communities. Appl Econ 2003;35(11):1331– 8. 21. Her M, Giesbrecht N, Room R, Rehm J. Privatizing alcohol sales and alcohol consumption: evidence and implications. Addiction 1999;94(8): 1125–39. 22. World Bank. World Development Indicators 2006. devdata.worldbank. org/wdi2006/contents/cover.htm. 23. Gruenewald PJ, Millar AB, Treno AJ, Yang Z, Ponicki WR, Roeper P. The geography of availability and driving after drinking. Addiction 1996; 91(7):967– 83. 24. Cook PJ, Skog OJ. Alcool, alcoolisme, alcoolisation: comment. Alcohol Health Res World 1995;19(1):30 –1. 25. Blake D, Nied A. The demand for alcohol in the United Kingdom. Appl Econ 1997;29:1655–72. 26. Gruenewald PJ, Ponicki WR, Holder HD. The relationship of outlet densities to alcohol consumption: a time series cross-sectional analysis. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 1993;17(1):38 – 47. 27. Gruenewald PJ, Remer L. Changes in outlet densities affect violence rates. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2006;30(7):1184 –93. 28. Hoadley JF, Fuchs BC, Holder HD. The effect of alcohol beverage restrictions on consumption: a 25-year longitudinal analysis. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse 1984;10(3):375– 401. 29. Markowitz S, Chatterji P, Kaestner R. Estimating the impact of alcohol policies on youth suicides. J Ment Health Policy Econ 2003;6(1):37– 46. 30. McCarthy P. Alcohol, public policy, and highway crashes: a time-series analysis of older-driver safety. Transp Econ Policy 2005;39(1):109 –25. 31. McCornac DC, Filante RW. The demand for distilled spirits: an empirical investigation. J Stud Alcohol 1984;45(2):176 – 8. 32. Norstrom T. Outlet density and criminal violence in Norway, 1960 –1995. J Stud Alcohol 2000;61(6):907–11. 33. Xie X, Mann RE, Smart RG. The direct and indirect relationships between alcohol prevention measures and alcoholic liver cirrhosis mortality. J Stud Alcohol 2000;61(4):499 –506. 34. Fitzgerald JL, Mulford HA. Consequences of increasing alcohol availability: the Iowa experience revisited. Br J Addict 1992;87(2):267–74. 35. Holder HD, Wagenaar AC. Effects of the elimination of a state monopoly on distilled spirits’ retail sales: a time-series analysis of Iowa. Br J Addict 1990;85:1615–25. 36. Trolldal B. The privatization of wine sales in Quebec in 1978 and 1983 to 1984. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2005;29(3):410 – 6. 37. MacDonald S. The impact of increased availability of wine in grocery stores on consumption: four case histories. Br J Addict 1986;81:381–7. 38. Mulford HA, Fitzgerald JL. Consequences of increasing off-premise wine outlets in Iowa. Br J Addict 1988;83(11):1271–9. 39. Mulford HA, Ledolter J, Fitzgerald JL. Alcohol availability and consumption: Iowa sales data revisited. J Stud Alcohol 1992;53(5):487–94. 40. Ramstedt M. The repeal of medium-strength beer in grocery stores in Sweden—the impact on alcohol-related hospitalizations in different age groups. Finland: Nordic Council for Alcohol and Drug Research (NAD), 2002. No. 42. 41. Smart RG, Docherty D. Effects of the introduction of on premise drinking on alcohol-related accidents and impaired driving. J Stud Alcohol 1976;37:683– 6. 42. Trolldal B. An investigation of the effect of privatization of retail sales of alcohol on consumption and traffic accidents in Alberta, Canada. Addiction 2005;100(5):662–71. 43. Wagenaar AC, Holder HD. A change from public to private sale of wine: results from natural experiments in Iowa and West Virginia. J Stud Alcohol 1991;52(2):162–73. 44. Wagenaar AC, Holder HD. Changes in alcohol consumption resulting from the elimination of retail wine monopolies: results from five U.S. states. J Stud Alcohol 1995;56(5):566 –72. 568 45. Fitzgerald JL, Mulford HA. Privatization, price and cross-border liquor purchases. J Stud Alcohol 1993;54(4):462– 4. 46. Smart RG. The impact on consumption of selling wine in grocery stores. Alcohol Alcohol 1986;21(3):233– 6. 47. Makela P. Whose drinking does the liberalization of alcohol policy increase? Change in alcohol consumption by the initial level in the Finnish panel survey in 1968 and 1969. Addiction 2002;97(6):701– 6. 48. Berman MHT. Alcohol control by referendum in Northern native communities: the Alaska local option law. Arctic 2001;54(1):77– 83. 49. Bowerman RJ. The effect of a community supported alcohol ban on prenatal alcohol and other substance abuse. Am J Public Health 1997;87(8):1378 –9. 50. Chiu AY, Perez PE, Parker RN. Impact of banning alcohol on outpatient visits in Barrow, Alaska. JAMA 1997;278(21):1775–7. 51. May P. Arrests, alcohol and alcohol legalization among an American Indian tribe. Plains Anthropol 1975;20(68):129 –34. 52. O’Neil JD. Community control over health problems: alcohol prohibition in a Canadian Inuit village. Int J Circumpolar Health 1984;84:340 –3. 53. Berman M, Hull T, May P. Alcohol control and injury death in Alaska native communities: wet, damp and dry under Alaska’s local option law. J Stud Alcohol 2000;61(2):311–9. 54. Gallaher MM, Fleming DW, Berger LR, Sewell CM. Pedestrian and hypothermia deaths among Native Americans in New Mexico: between bar and home. JAMA 1992;267(10):1345– 8. 55. Britt H, Carlin BP, Toomey TL, Wagenaar AC. Neighborhood-level spatial analysis of the relationship between alcohol outlet density and criminal violence. Environ Ecol Stat 2005;12:411–26. 56. Escobedo LG, Ortiz M. The relationship between liquor outlet density and injury and violence in New Mexico. Accid Anal Prev 2002;34(5):689 –94. 57. Parker DA, Wolz MW, Harford TC. The prevention of alcoholism: an empirical report on the effects of outlet availability. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 1978;2(4):339 – 43. 58. Treno AJ, Gruenewald PJ, Johnson FW. Alcohol availability and injury: the role of local outlet densities. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2001;25(10):1467–71. 59. Wood DS, Gruenewald PJ. Local alcohol prohibition, police presence and serious injury in isolated Alaska Native villages. Addiction 2006;101(3):393– 403. 60. Olafsdottir H. The dynamics of shifts in alcoholic beverage preference: effects of the legalization of beer in Iceland. J Stud Alcohol 1998; 59(1):107–14. 61. Wagenaar AC, Langley JD. Alcohol licensing system changes and alcohol consumption: introduction of wine into New Zealand grocery stores. Addiction 1995;90(6):773– 83. 62. Blose JO, Holder HD. Public availability of distilled spirits: structural and reported consumption changes associated with liquor-by-the-drink. J Stud Alcohol 1987;48(4):371–9. 63. Dull RT. An assessment of the effects of alcohol ordinances on selected behaviors and conditions. J Drug Issues 1986;16(4):511–21. 64. Dull RT. Dry, damp, and wet: correlates and presumed consequences of local alcohol ordinances. Am Drug Alcohol Abuse 1988;14(4):499 –514. 65. Gorman DM, Speer PW, Labouvie EW, Subaiya AP. Risk of assaultive violence and alcohol availability in New Jersey. Am J Public Health 1998;88(1):97–100. 66. Gorman DM, Labouvie EW, Speer PW, Subaiya AP. Alcohol availability and domestic violence. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse 1998;24(4):661–73. 67. Gorman D, Speer P, Gruenewald P, Labouvie E. Spatial dynamics of alcohol availability, neighborhood structure and violent crime. J Stud Alcohol 2001;62(5):628 –36. 68. Gyimah-Brempong K. Alcohol availability and crime: evidence from census tract data. South Econ J 2001;68(1):2–21. 69. Jewell R, Brown R. Alcohol availability and alcohol-related motor vehicle accidents. Appl Econ 1995;27:759 – 65. 70. Markowitz S, Grossman M. Alcohol regulation and domestic violence towards children. Contemp Econ Policy 1998;16(3):309 –20. 71. Neuman C, Rabow J. Drinkers’ use of physical availability of alcohol: buying habits and consumption level. Inter Addict 1985;20(11–12):1663–73. 72. Nielsen AL, Martinez R, Lee MT. Alcohol, ethnicity, and violence: the role of alcohol availability for Latino and Black aggravated assaults and robberies. Sociol Q 2005;46:479 –502. 73. Ornstein S, Hanssens D. Alcohol control laws and the consumption of distilled spirits and beer. J Consum Res 1985;12(2):200 –13. 74. Parker DA. Alcohol problems and the availability of alcohol. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 1979;3(4):309 –12. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, Volume 37, Number 6 www.ajpm-online.net 75. Pollack CE, Cubbin C, Ahn D, Winkleby M. Neighbourhood deprivation and alcohol consumption: does the availability of alcohol play a role? Int J Epidemiol 2005;34(4):772– 80. 76. Reid RJ, Hughey J, Peterson NA. Generalizing the alcohol outlet-assaultive violence link: evidence from a U.S. Midwestern city. Subst Use Misuse 2003;38(14):1971– 82. 77. Rush BR, Gliksman L, Brook R. Alcohol availability, alcohol consumption and alcohol-related damage. I. The distribution of consumption model. J Stud Alcohol 1986;47(1):1–10. 78. Scribner RA. The risk of assaultive violence and alcohol availability. Am J Public Health 1995;85(3):335– 40. 79. Scribner RA, MacKinnon DP, Dwyer JH. Alcohol outlet density and motor vehicle crashes in Los Angeles County cities. J Stud Alcohol 1994;55(4):447–53. 80. Smart RG. Effects of two liquor store strikes on drunkenness, impaired driving and traffic accidents. J Stud Alcohol 1977;38(9):1785–9. 81. Speer PW, Gorman DM, Labouvie EW, Ontkush MJ. Violent crime and alcohol availability: relationships in an urban community. J Public Health Policy 1998;19(3):303–18. 82. Stevenson RJ, Lind B, Weatherburn D. The relationship between alcohol sales and assault in New South Wales, Australia. Addiction 1999;94(3):397– 410. 83. Tatlow JR, Clapp JD, Hohman MM. The relationship between the geographic density of alcohol outlets and alcohol-related hospital admissions in San Diego County. J Community Health 2000;25(1):79 – 88. 84. Treno A, Grube J, Martin S. Alcohol availability as a predictor of youth drinking and driving: a hierarchical analysis of survey and archival data. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2003;27(5):835– 40. 85. Weitzman ER, Folkman A, Folkman MP, Wechsler H. The relationship of alcohol outlet density to heavy and frequent drinking and drinkingrelated problems among college students at eight universities. Health Place 2003;9(1):1– 6. 86. Zhu L, Gorman DM, Horel S. Alcohol outlet density and violence: a geospatial analysis. Alcohol Alcohol 2004;39(4):369 –75. 87. Colon I. Alcohol availability and cirrhosis mortality rates by gender and race. Am J Public Health 1981;71(12):1325– 8. 88. Colon I, Cutter HS. The relationship of beer consumption and state alcohol and motor vehicle policies to fatal accidents. J Safety Res 1983;14(2):83–9. 89. Freisthler B, Gruenewald PJ, Treno AJ, Lee J. Evaluating alcohol access and the alcohol environment in neighborhood areas. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2003;27(3):477– 84. 90. Freisthler B. A spatial analysis of social disorganization, alcohol access, and rates of child maltreatment in neighborhoods. Child Youth Serv Rev 2004;26(9):803–19. 91. Freisthler B, Needell B, Gruenewald PJ. Is the physical availability of alcohol and illicit drugs related to neighborhood rates of child maltreatment? Child Abuse Negl 2005;29(9):1049 – 60. 92. Godfrey C. Licensing and the demand for alcohol. Appl Econ 1988;20:1541–58. 93. Harford T, Parker D, Pautler C, Wolz M. Relationship between the number of on-premise outlets and alcoholism. Stud Alcohol 1979;40(11):1053–7. 94. Gruenewald PJ, Johnson FW, Treno AJ. Outlets, drinking and driving: a multilevel analysis of availability. J Stud Alcohol 2002;63(4):460 – 8. 95. Kelleher KJ, Pope SK, Kirby RS, Rickert VI. Alcohol availability and motor vehicle fatalities. J Adolesc Health 1996;19(5):325–30. 96. Lascala EA, Gerber D, Gruenewald PJ. Demographic and environmental correlates of pedestrian injury collisions: a spatial analysis. Accid Anal Prev 2000;32:651– 8. December 2009 97. LaScala EA, Johnson FW, Gruenewald PJ. Neighborhood characteristics of alcohol-related pedestrian injury collisions: a geostatistical analysis. Prev Sci 2001;2(2):123–34. 98. Lipton R, Gruenewald P. The spatial dynamics of violence and alcohol outlets. J Stud Alcohol 2002;63(2):187–95. 99. Rabow J, Watts RK. Alcohol availability, alcoholic beverage sales and alcohol-related problems. J Stud Alcohol 1982;43(7):767– 801. 100. Roncek DW, Maier PA. Bars, blocks, and crimes revisited: linking the theory of routine activities to the empiricism of “hot spots.” Criminology 1991;29(4):725–53. 101. Scribner R, Cohen D, Kaplan S, Allen SH. Alcohol availability and homicide in New Orleans: conceptual considerations for small area analysis of the effect of alcohol outlet density. J Stud Alcohol 1999;60(3):310 – 6. 102. Stout EM, Sloan FA, Liang L, Davies HH. Reducing harmful alcohol-related behaviors: effective regulatory methods. J Stud Alcohol 2000;61(3):402–12. 103. Watts RK. Alcohol availability and alcohol-related problems in 213 California cities. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 1983;7(1):47–58. 104. Wieczorek WF, Coyle JJ. Targeting DWI prevention. J Prev Interv Community 1998;17(1):15–30. 105. van Oers JA, Garretsen HF. The geographic relationship between alcohol use, bars, liquor shops and traffic injuries in Rotterdam. J Stud Alcohol 1993;54(6):739 – 44. 106. Alaniz ML. Immigrants and violence: the importance of neighborhood context. Hisp J Behav Sci 1998;20(2):155–74. 107. Cohen DA, Mason K, Scribner R. The population consumption model, alcohol control practices, and alcohol-related traffic fatalities. Prev Med 2002;34(2):187–97. 108. Colon I. The influence of state monopoly of alcohol distribution and the frequency of package stores on single motor vehicle fatalities. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse 1982;9(3):325–31. 109. Freisthler B, Midanik LT, Gruenewald PJ. Alcohol outlets and child physical abuse and neglect: applying routine activities theory to the study of child maltreatment. J Stud Alcohol 2004;65(5):586 –92. 110. Gorman DM, Zhu L, Horel S. Drug ‘hot-spots,’ alcohol availability and violence 220. Drug Alcohol Rev 2005;24(6):507–13. 111. Scribner RA, Cohen DA, Fisher W. Evidence of a structural effect for alcohol outlet density: a multilevel analysis. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2000;24(2):188 –95. 112. McCarthy PS. Public policy and highway safety: a city-wide perspective. Reg Sci Urban Econ 1999;29(2):231– 44. 113. Wittman FD, Hilton ME. Uses of planning and zoning ordinances to regulate alcohol outlets in California cities. In: Holder HD, ed. Control issues in alcohol abuse prevention: strategies for states and communities. Greenwich CT: JAI Press, 1987:337– 66. 114. Donnelly N, Poynton S, Weatherburn D, Bamford E, Nottage J. Liquor outlet concentrations and alcohol-related neighborhood problems. Alcohol Stud Bull 2006;8:1–16. 115. Giesbrecht N. Roles of commercial interests in alcohol policies: recent developments in North America. Addiction 2000;95(4):S581–95. 116. National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. The role of alcohol beverage control agencies in the enforcement and adjudication of alcohol laws. No. DOT HS 809 877. 117. Mann R, Rehm J, Giesbrecht N, et al. The effect of different forms of alcohol distribution and retailing on alcohol consumption and problems—an analysis of available research. Toronto: Center for Addiction and Mental Health, 2005. Am J Prev Med 2009;37(6) 569