Riding time and school size as factors in the achievement... by Alan George Zetler

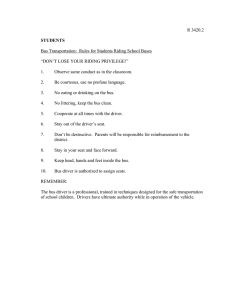

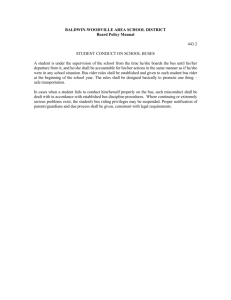

advertisement