Document 13487452

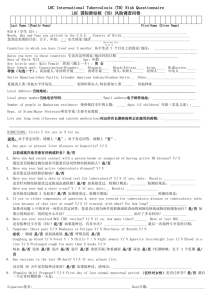

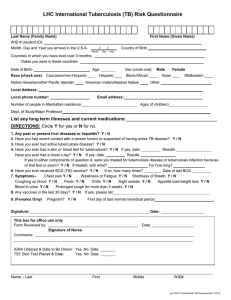

advertisement