A cost analysis of instruction at Montana State University

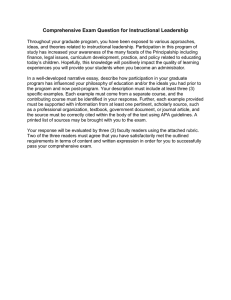

advertisement