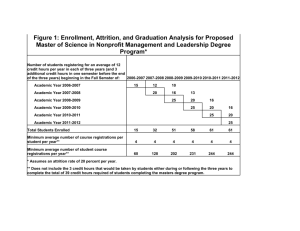

The effect of course section size on the cost of... by Jacob Robert Hehn

advertisement