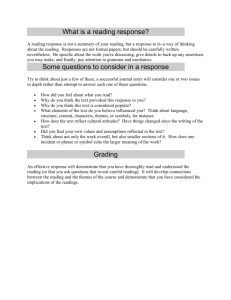

Criteria for the evaluation of high school English compostion

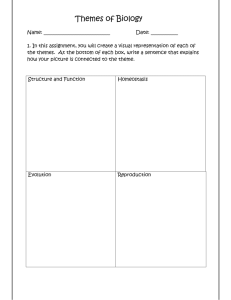

advertisement