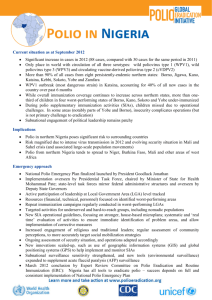

GLOBAL POLIO ERADICATION INITIATIVE (GPEI) STATUS REPORT 20 APRIL 2015

advertisement