REBIRTH OF IDENTITY by Raluca Miriam Vandergrift

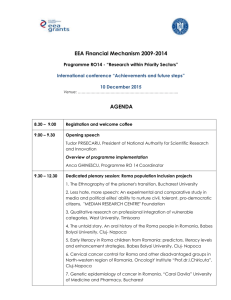

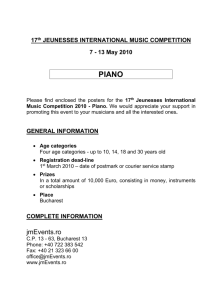

advertisement