Document 13470922

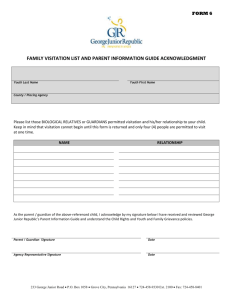

advertisement