TEXTBOOK READING STRATEGIES IN THE MIDDLE SCHOOL SCIENCE CLASSROOM by

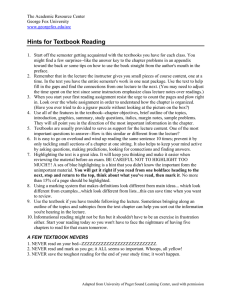

advertisement