AN ECONOMIC ANALYSIS OF VARIABLE RATE NITROGEN MANAGEMENT by

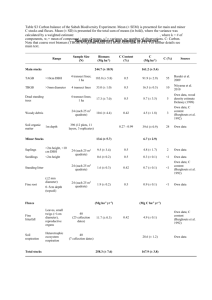

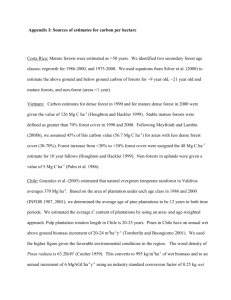

advertisement