The National Academy for Gifted and Talented Youth:

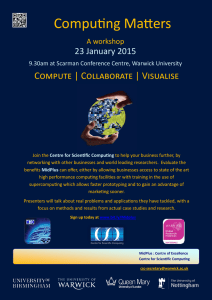

advertisement