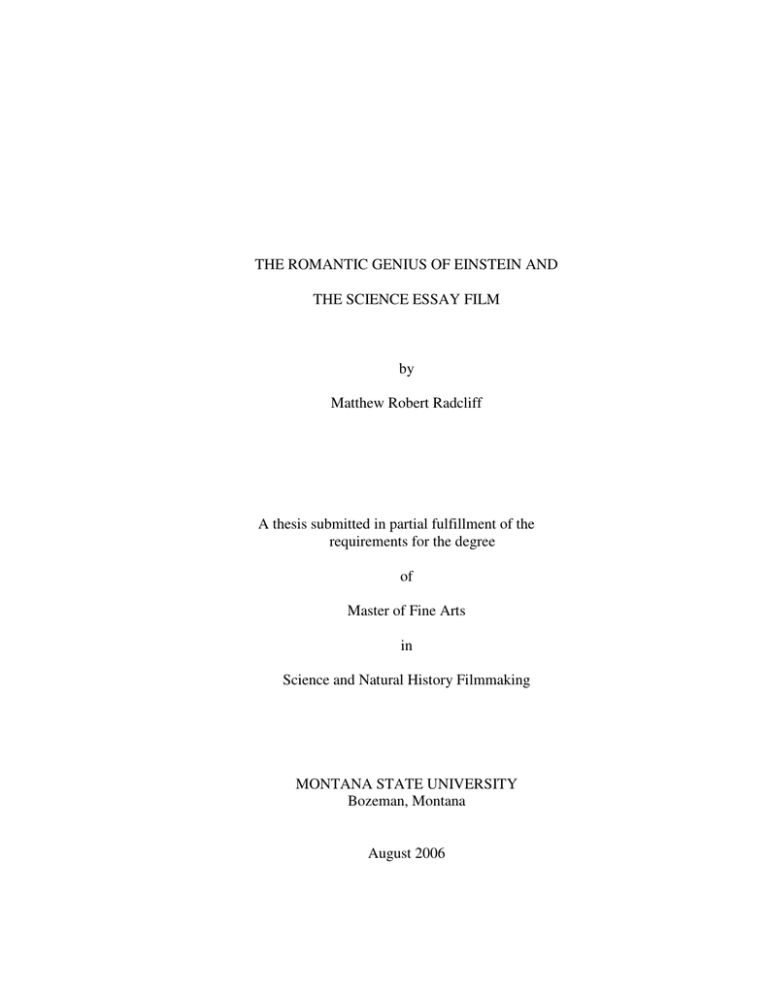

THE ROMANTIC GENIUS OF EINSTEIN AND THE SCIENCE ESSAY FILM by

advertisement