REVIEW AND COMPARISON OF THREE CULTURAL COMPETENCY EDUCATION PROGRAMS FOR NURSES By

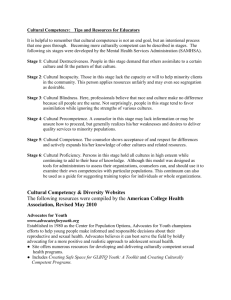

advertisement