ENVIRONMENTAL RISK REDUCTION THROUGH NURSING INTERVENTION

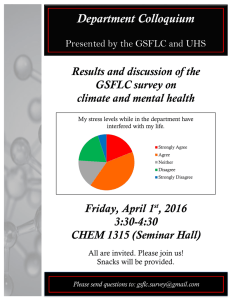

advertisement