ADVOCATING FOR ADVANCE DIRECTIVES: GUIDELINES FOR HEALTH CARE PROFESSIONALS by

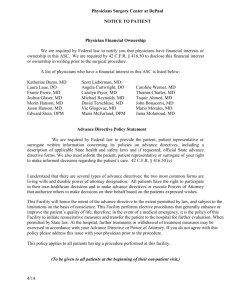

advertisement