INFUSION: URBAN AND DOMESTIC TRANSFORMATION by Dylan Thomas McQuinn

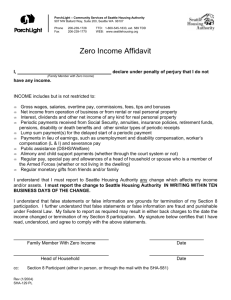

advertisement