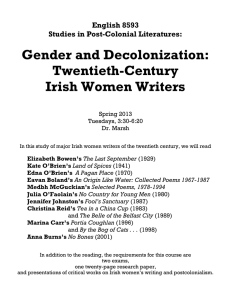

EDNA O’BRIEN: CENSORSHIP, SEXUALITY AND DEFINING THE “OTHER” by

advertisement