DAR ES SALAAM

advertisement

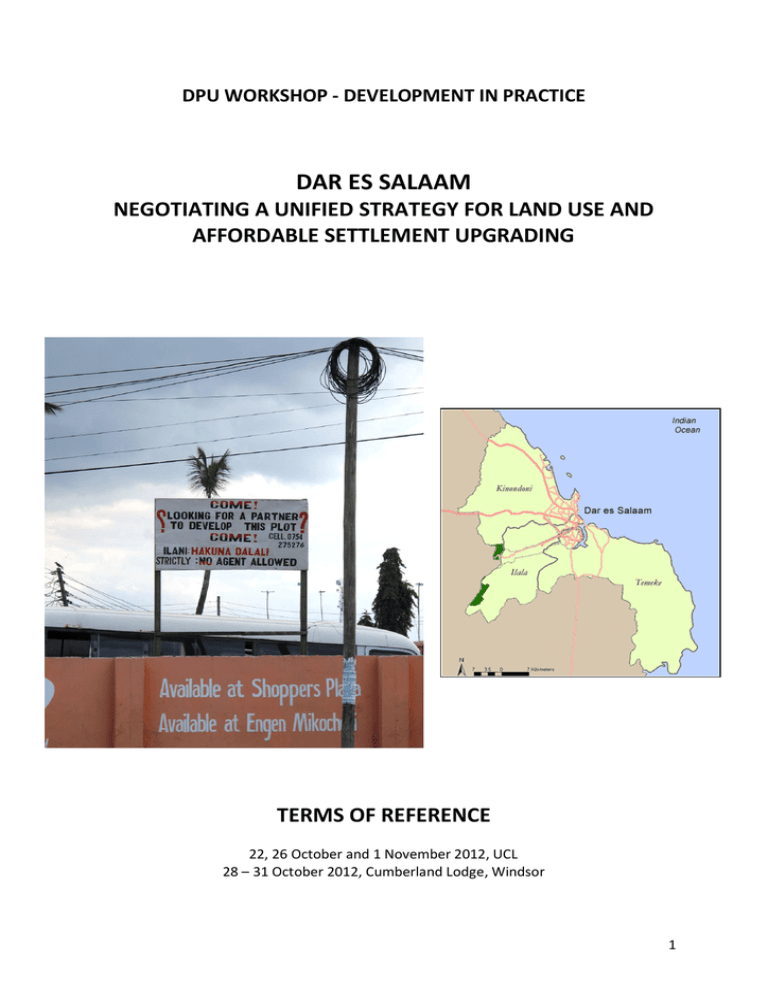

DPU WORKSHOP -­‐ DEVELOPMENT IN PRACTICE DAR ES SALAAM NEGOTIATING A UNIFIED STRATEGY FOR LAND USE AND AFFORDABLE SETTLEMENT UPGRADING TERMS OF REFERENCE 22, 26 October and 1 November 2012, UCL 28 ʹ 31 October 2012, Cumberland Lodge, Windsor 1 AIMS OF THE WORKSHOP The aim of the workshop is to explore the planning and investment options, priorities and practical interventions that a range of actors can use to influence how a city develops. There are three specific objectives: 1. To explore the motivations and capacities of a range of different actors with interests in future city development 2. To introduce participants to a diagnostic tool that can assist them in assessing opportunities for sustainable and equitable city development. 3. To introduce participants to a process of dialogue and negotiation aimed at creating a just and sustainable land and settlement development strategy for Dar es Salaam. CREDITS The workshop is being led by Ruth McLeod and Kamna Patel. Alicia Yon assisted with important background research and logistics. Gynna Millan Franco co-­‐ordinated the development and use of documentary media. Sharon Cooney, Yukiko Fujimoto and other members of the Administration Team have ensured that the practical arrangements are in place. Julian Walker and Colin Marx are providing specialist input, as is Remi Kaup from Homeless International. Julio Davila and members of the DPU teaching staff and GTAs are facilitating discussions and presentations. A major role has been played by the Tanzanian Team: Tim Ndezi, Mwanakombo Mkanga, Stella, Ali, John and the rest of the Centre for Community Initiatives staff. Members of the Tanzanian Federation of the Urban Poor have been generous in sharing their experiences, as have all the many individuals in Tanzania who participated in discussions and agreed to share their opinions on camera. Particular thanks are extended to Cumberland Lodge, Windsor and to the Mayfair Hotel in Dar es Salaam. ACRONYMS CCI CLIFF HI Centre for Community Initiatives Community Led Infrastructure Finance Facility Financial Services Deepening Trust Homeless International MFI Micro Finance Institution FSDT SACCO SDI Savings and Credit Cooperative Slum/Shack Dwellers International TAFSUS Tanzania Financial Services for Underserved Settlements TFUP Tanzanian Federation of the Urban Poor MLHHSD Ministry of Lands Housing and Human Settlements Development OVERVIEW Dar es Salaam is the ůĂƌŐĞƐƚĐŝƚLJŝŶdĂŶnjĂŶŝĂ͘/ƚŝƐŽŶĞŽĨƚŚĞǁŽƌůĚ͛ƐĨĂƐƚĞƐƚŐƌŽǁŝŶŐĐŝƚŝĞƐ͘dŚĞ population has doubled over the last twenty years and now stands at more than four million1. Nearly 80% of the people live in informal and unplanned settlements with few or no basic services. These settlements are growing rapidly. There is no operational development plan for the city and the City Council and three Municipalities that administer Dar es Salaam are under-­‐resourced. There is Source of map: Coastal Forests of Kenya and Tanzania (2012) 1 UN Habitat (2010) 2 significant commercial pressure on land. In recent times relocation of informal settlement residents has resulted from major infrastructure developments including expansion of the port and the construction of a mass rapid urban transport system. Major flooding in 2011 is illustrative of the increase in vulnerability of coastal settlements to climate change. Whilst there is a recognized responsibility by Government to ensure that compensations is paid to those evicted from structures that they own, no such responsibility is acknowledged for tenants. OUR STARTING POINT A Tanzanian Federation of the Urban Poor (TFUP) was established in 2004. It is made up of members of savings and loan groups that have formed in informal settlements in urban areas throughout the country. TFUP is supported by a local non-­‐government organization ʹ the Centre for Community Initiatives (CCI). Both organisations are linked into a wider international network of slum/shack dwellers and their support agencies known as Slum Dwellers International (SDI). Supported by CCI, TFUP members carry out settlement mapping and enumerations and use the information they collect to try to negotiate solutions that can work for people living in informal settlements as well as other stakeholders. They also have an Urban Poor Fund. CCI and TFUP are working closely with the three Municipalities of Kinondoni, Ilala and Temeke to establish partnership approaches to settlement development that work for slum dwellers and the Municipalities. Recent work has focused on two specific initiatives: The first initiative is a new community led process within the Temeke Municipal boundaries. Major works are underway to expand the port in Kurasini, affecting around 36,000 residents. Three quarters of the residents are tenants who rent the structures they live in. In October 2007, the first evictions took place and 2,000 people (600 households consisting of both structure owners and tenants) from Kurasini were ordered to leave their homes in preparation for large-­‐scale demolitions. In response, 300 tenant families organised under the auspices of the Tanzania Federation of the Urban Poor (TFUP) saved enough money to buy a 30 acre plot of land 20 kilometres away in Chamazi Ward. They are currently in the process of developing that land. The second initiative is an attempt to address the problems and displacement associated with major flooding in Tandale and Magomeni Districts of Kinondoni Municipality in 2011. The floods are thought to be associated with climate change and some argue that they are likely to become increasingly common. Many of the flood victims have been relocated to temporary tent accommodation 26 kilometres away at Mabwepande. Those affected by the floods face the challenge of deciding on the best options ʹ fighting to stay where they are and investing in flood preparedness and mitigation or investing in the development of new homes and facilities in Mabwepande. CHALLENGES One of the major challenges faced by TFUP and CCI is that of finance. Community-­‐led land development requires access to medium and long-­‐term finance and this is not readily available from conventional banks. New financing mechanisms have therefore had to be developed and are currently being piloted with capital being sourced internationally as well as locally. Homeless International, a UK NGO is providing specialist help in designing and accessing new forms of financing. Apart from community organisations, local government and financial institutions, there are many other agencies that need to be involved in the development of a unified approach to land and 3 settlement development within Dar es Salaam. TFUP and CCI are working to establish relationships with many of them. This workshop begins with the challenges that TFUP and CCI face at the moment in specific locations and contexts. The aim is to explore how a broader and more strategic approach to city development that is just and sustainable can be negotiated in practice. A BRIEF BACKGROUND TO TANZANIA AND DAR ES SALAAM History The United Republic of Tanzania was founded in 1964, three years after Tanganyika and Zanzibar gained Independence from British colonial rule. Under colonial rule (first German, then British from 1919), Dar es Salaam was developed into a commercial city with major investments in buildings, roads and harbour defences to encourage foreign investment and trade. In order to manage the city and its potential for wealth, German colonial administrators enacted racial zoning of the city. The 1891 Building Ordinance enacted separate building standards across the city based on race: European settlers had the highest standard of building, Indian and Arab residents were confined to mostly stone buildings in certain parts of the city, and African residents to wattle and daub structures, which meant that they were relatively easy to relocate, should demands for labour require it (Brennan and Burton, 2007). Under the British, racial zoning in Dar es Salaam was more forcefully implemented. Zones saw European settlers clustered north of the city centre along the sea front, Asian residents clustered in the city centre where trade and commerce took place, and African residents were pushed to the southern periphery of the city where infrastructure was poor and few investments were made by the state. Post-­‐World War 2, urbanisation, a post-­‐war economic boom and political pressures for change facilitated a significant challenge to racial zoning and began to give the city its contemporary feel as a racially mixed (though perhaps not integrated) cosmopolitan city. Independence for the country came in December 1961 when Julius Nyerere, leader and founder of the Tanganyika African National Union (TANU), was elected first as Prime Minister, and later as President (1962). Political system Tanzania is a presidential democracy. This means the president of the country is the Head of State and Head of Government. Between 1961 until 1992 the country was a one party state (headed by the President). Following a Constitutional amendment in 1992, Tanzania is now a multi-­‐party democracy. The first multi-­‐party elections were held in 1994. While the theory of a multi-­‐party state has been enshrined in the Constitution, in reality, the Chama Cha Mapinduzi (CCM) ʹ the party established by Julius Nyerere, has dominated and won every national election. At Independence, Tanzania was led by a strong and respected leader in Nyerere. He developed a social, political and economic system called Ujamaa ĂůƐŽŬŶŽǁŶĂƐ͚ĨƌŝĐĂŶ^ŽĐŝĂůŝƐŵ͛͘/ƚĞŵƉŚĂƐŝƐĞĚ individuals working together to achieve collective prosperity and focused on a programme of ͞villagisation͟ (collectivised agricultural production) and the nationalisation of key sectors in the economy. Its philosophy drew on the fact that despite the many different ethnic groups in Tanzania, Swahili served as a common language, and demonstrated commonality across diversity. Over the years this haƐĐŽŶƚƌŝďƵƚĞĚƚŽĂƐƚƌŽŶŐ͚dĂŶnjĂŶŝĂŶ͛ŝĚĞŶƚŝƚLJ͘ůƚŚŽƵŐŚŝŶĐŝƚŝĞƐƐŽĐŝĂůƚĞŶƐŝŽŶƐďĞƚǁĞĞŶ inhabitants along class, wealth, race and ethnic lines exist most sources suggest that these tensions are considerably lower than in other East African cities with a similar socio-­‐cultural mix (e.g. Boyle, 2012). 4 ƵƌŝŶŐELJĞƌĞƌĞ͛ƐϮϰLJĞĂƌƌƵůĞ͕ĐƌĂĐŬƐŝŶUjamaa became apparent. The forced adoption of Ujamaa policies led to mass relocation and ensuing political dissent (which was crushed), inefficiency in food productioŶĂŶĚƚŚĞƐƚĂƚĞ͛ƐĐŽŶƚƌŽůŽĨĞĐŽŶŽŵŝĐĂŶĚƉŽůŝƚŝĐĂůůŝĨĞǀŝĂŽŶĞƉŽůŝƚŝĐĂůƉĂƌƚLJ͕ůĞĨƚƐƚĂƚĞ institutions open to corruption and the misappropriation of public funds. The resignation of Nyerere in 1985 and IMF loans to the country around the same time, saw the new president Ali Mwinyi usher in a period of market-­‐based reforms and the dismantling of a command economy. Demographics /ŶϮϬϭϭ͕dĂŶnjĂŶŝĂ͛ƐƉŽƉƵůĂƚŝŽŶǁĂƐĞƐƚŝŵĂƚĞĚƚŽďĞϰϲ͘ϮŵŝůůŝŽŶƉĞŽƉůĞ;hEĚĂƚĂ͕ϮϬϭϮͿ͘ Approximately 74 per cent of the total population lives in rural areas. Based on the 2011 population estimate, 45 per cent of the total population are between the ages of 0 ʹ 14 years, 52 per cent are between 15 ʹ 64 years old, and 3 per cent are older than 65 years. Tanzania has a very young population (World DataBank, 2012). The country is an ethnic, racial and religious mix. There are three main religious or spiritual traditions that are followed in Tanzania: Christianity, Islam and cultural practices rooted in traditional African indigenous practices. Religious classifications are problematic as these questions are not directly asked in the national census. The majority (99%) ŽĨdĂŶnjĂŶŝĂ͛ƐƉŽƉƵůĂƚŝŽŶŝƐĨƌŝĐĂŶ in origin, coming from over 130 different tribes associated with the region. The remaining one per cent is of South Asian, European and Arab descent. The racial, ethnic and religious diversity of Tanzania is amplified in Dar es Salaam, where the majority of Tanzanians of non-­‐ĨƌŝĐĂŶĚĞĐĞŶƚůŝǀĞ͘dŚĞƉƌĞĐŝƐĞƌĂĐŝĂůĂŶĚĞƚŚŶŝĐŵŝdžŽĨĂƌĞƐ^ĂůĂĂŵ͛Ɛ residents is impossible to know, particularly as urbanisation and the migration of national and international people continually changes the social mix. International migration is mainly from neighbouring African countries and tends to peak in response to natural disasters and conflict in these countries. Economy Under President Mwinyi, the country signed up to an IMF/World Bank designed Structural Adjustment Programme in the mid-­‐1980s. Under this programme, the economy was liberalised which entailed the reduction of a civil service, drastic cuts to social spending, and the introduction of user fees to health, education and water services that were free or heavily subsidised by the state under Nyerere. Contemporary approaches to economic development tend to focus on the strict management of national funds under a streamlined and largely decentralised public sector. Such an approach has contributed to the macroeconomic stability of the country; GDP growth had been steady with annual increases of 7.2 per cent between 2002 and 2008 2. The Tanzanian economy is dominated by agriculture although there are strong efforts to diversify through manufacturing, mining, construction and transport activities. Most efforts to diversify have focused at city level, particularly Dar es Salaam, which drives industrial growth in the country. GDP per capita is significantly higher in Dar es Salaam than in any other part of the country, which helps ƚŽĞdžƉůĂŝŶŝƚƐĂƚƚƌĂĐƚŝŽŶƚŽŵŝŐƌĂŶƚƐ͘dŚĞĐŝƚLJ͛ƐĞĐŽŶŽŵLJŝƐĚƌŝǀĞŶďLJůŝŐŚƚŝŶĚƵƐƚƌLJĂŶĚ manufacturing for domestic consumption and export. The types of industry include: textiles, food production, brewery and distillery, pharmaceuticals, production of plastic and metal products, and printing and publishing. 2 United Republic of Tanzania (2011), National Accounts of Tanzania Mainland 2000-­‐2010, National Bureau of Statistics/Ministry of Finance, September 2011 5 Land >ĂŶĚŝƐŽŶĞŽĨƚŚĞĨŽƵƌƉŝůůĂƌƐŽĨdĂŶnjĂŶŝĂ͛ƐĚĞǀĞůŽƉŵĞŶƚƉŚŝůŽƐŽƉŚLJ͗ƉĞŽƉůĞ͕ůĂŶĚ͕ŐŽŽĚƉŽůŝĐŝĞƐĂŶĚ good leadership. At Independence, land was governed under a range of tenure systems including formal freehold titles (usually held by settlers of European decent) and customary systems under Chieftaincy arrangements that applied to majority African citizens. Under the socialist principles that governed the country under Nyerere, freehold titles were revoked and replaced with leases that were subject to state conditions on land use and length of occupation. The right to occupy land was introduced as a key concept and was central to provide secure tenure and manage land speculation, particularly by foreign non-­‐citizens. By the 1990s Ujamaa, as a policy, was abandoned, and a new era of investment promotion had begun. The Ministry of Lands was tasked with preparing an investor-­‐ĨƌŝĞŶĚůLJůĂŶĚƉŽůŝĐLJƚŚĂƚĂůƐŽƐĂĨĞŐƵĂƌĚĞĚĐŝƚŝnjĞŶ͛ƐƌŝŐŚƚƐƚŽůĂŶĚƚĞŶƵƌĞ͕ĂƚĂƐŬƚŚĂƚƌĞƋƵŝƌĞƐ the careful management of customary and statutory land rights (see Government of Tanzania National Land Policy, 2007). The growth of Dar es Salaam through continual migration and high urban birth rates has seen a steady increase in the use of (apparently) available land for residence. Along the main roads running in and out of the city, where there is electricity and potable water, the density of dwellings is highest; ĂůŵŽƐƚĂůůŽĨŝƚŝƐŝŶĨŽƌŵĂůĂŶĚƵŶƉůĂŶŶĞĚ͘>ĂŶĚŝƐǀĞƌLJŝŵƉŽƌƚĂŶƚƚŽƚŚĞƌĞƐŝĚĞŶƚƐŽĨĂƌĞƐ^ĂůĂĂŵ͛Ɛ many informal settlements ʹ it not only offers a space to build shelter, but a space to generate livelihoods. Secure tenure of land therefore aids resilience and can help urban households deal with shocks to their income Since 2005, the government has implemented a programme to formalise property rights in the informal settlements of Dar es Salaam. This programme aims to identify, demarcate, adjudicate where there is conflict, and award short-­‐term 5-­‐year licenses for residential land use on a particular parcel of land as part of an incremental approach to formalise and secure tenure. However, the programme is outpaced by the growth of new and existing informal settlements (Kombe, 2010). It is also limited to a few high-­‐density well-­‐established settlements in the city and does not currently extend to peri-­‐urban settlements skirting the city. Matters relating to urban land governance fall under the aegis of the local municipalities. They are responsible for identifying land for planning and development, amongst other tasks. Once land has been identified, they coordinate with the Ministry of Lands, Housing and Human Settlements Development, for land acquisition and any compensation payments. Typically, the local municipality will coordinate with the Ward and Mitaa level to mobilise residents to identify owners (for compensation), raise issues relating to the land and any planned development, and ideally to consult with residents on any land development plans. The process can be highly contentious and open to conflict. Planning policy dŚĞƐƚĂƚĞ͛ƐƉŽůŝĐLJŽŶƉůĂŶŶŝŶŐŝŶƵƌďĂŶĂƌĞĂƐǁĂƐĚĞǀĞůŽƉĞĚŝŶϭϵϵϳŝŶĂŶƚŝĐŝƉĂƚŝŽŶŽĨƵƌďĂŶŝƐĂƚŝŽŶ ĂŶĚƚŚĞĞdžƉĂŶƐŝŽŶŽĨdĂŶnjĂŶŝĂ͛ƐŵĂũŽƌĐŝƚŝĞƐĂŶĚƚŽǁŶƐ͘WůĂŶŶŝŶŐƉŽůŝĐLJŝƐĂƌƚŝĐƵůĂƚĞĚŝŶƚŚĞEĂƚŝŽŶĂů Land Policy thus: ͞;ŝ) The Government will institute measures to limit the loss of agricultural land to urban growth by controlling lateral expansion of all towns. In addition to minimising the demand for urban building land, both compact development and vertical extension of buildings will (a) reduce the costs of installing, operating and repair of infrastructure facilities and utilities, and (b) shorten intra-­‐urban distances. Both the nation and individuals will save on the time and costs of travel between different areas of towns. (ii) Urban land use and development plans will aim at more intensive use of urban land 6 To achieve these objectives the Government will undertake the following: (a) revise all space and planning standards, including standards for provision of infrastructure to promote more compact form of buildings in all urban areas; (b) zone out more areas of towns for vertical development so that whenever it is socially acceptable, and technically and economically feasible, more dwelling units will be accommodated in the residential plots. Within town centres and in the immediate surroundings of ƚŽǁŶĐĞŶƚƌĞƐ͕ǀĞƌƚŝĐĂůĞdžƚĞŶƐŝŽŶǁŝůůĐŽŶƐƚŝƚƵƚĞƚŚĞƉƌŝŶĐŝƉĂůďƵŝůĚŝŶŐĨŽƌŵ͘͟ (Government of Tanzania, 1997, section 6.1.2) Planning system The informal settlements that occupy the majority of land in Dar es Salaam are characterised by poor infrastructure and a lack of basic municipal services. Existing settlements are under pressure; they are growing in size and density because of urban migration. The growth of new informal settlements and expansion of existing ones has resulted in encroachments onto environmentally sensitive land e.g. floodplains and hillsides, increasing the vulnerability of these city residents (see START Secretariat, 2011). Existing infrastructure, particularly in unplanned or poor areas of the city, is deteriorating under population pressure. The informal nature of much of the residence of Dar es Salaam affects city revenue (through property rates and land tax, for example) and thus the ability of the city administration to maintain or expand infrastructure and basic services. Under official land planning policy (Government of Tanzania, 1997), the state aims to tackle informal settlement by building new areas for settlement on the periphery of cities, to designate low-­‐income housing areas with affordable services, a policy preference for in situ upgrade over relocation (unless housing is in a hazardous area), and to ensure all upgrading plans are designed and implemented by local authorities in collaboration with residents and community organisations. Upgrading plans are expected to take cost recovery into account. Universities There are several universities in Dar es Salaam including the University of Dar es Salaam, the Open University of Tanzania, the Hubert Kairuki Memorial University, the International Medical and Technological University and Ardhi University. Ardhi University is the university with the greatest focus on issues relating to urban development. It is owned by the Government of Tanzania, and was established in its present form in2007. It was previously known as the University College of Lands and Architectural Studies (UCLAS) and the Ardhi Institute. There are six schools in the University -­‐ Architecture and Design; of Construction Economics and Management; of Geospatial Sciences and Technology; of Real Estates Studies; of Urban and Regional Planning; and of Environmental Sciences and Technology Banking and financial services Socialist principles governed the banking system from the 1960s. The central premise of a social banking system assumes that lending decisions are determined by state priorities rather than market criteria. In the 1960s under Nyerere, the main commercial banks in Tanzania were nationalised and ƉůĂĐĞĚƵŶĚĞƌƐƚĂƚĞŽǁŶĞƌƐŚŝƉ͘dŚĞƐƚĂƚĞ͛ƐŵŽŶŽƉŽůLJŽŶďĂŶŬŝŶŐĞŶĐŽƵƌĂŐĞĚĂůŝŵŝƚĞĚrange of financial products and services (banks did not need to compete with each other for customers by offering a range of services and competitive prices). In this uncompetitive environment banks were able to survive through state subsidies. Under liberalisation in the 1990s, the banking sector was reformed with the aim of shifting from a state orientation to a market one. The purpose of the reforms was to make the banking sector more competitive in order to present greater financial choice to customers, and to make banks profitable 7 to reduce their dependence on the central bank and thereby the state. The main reforms included changes to legislation to encourage foreign banks in Tanzania, and greater accountability of the banks not to the state, but to customers, shareholders and regulators. Almost all major international banks have a commercial operation in Tanzania. Originally, microfinance provision in the country and especially in Dar es Salaam, was the preserve of NGOs and credit and saving groups. Increasingly commercial banks are offering microfinance services to customers under the encouragement of the state as part of its 2000 National Microfinance Policy (Government of Tanzania, 2000). Microfinance appears to be regarded by the state as a relatively low cost, low maintenance way to support poverty alleviation. While the Ministry of Finance oversees the implementation of the microfinance policy, the lending itself is done by private or third sector institutions (e.g. NGOs and savings and credit cooperatives), the state is not involved in this capacity. In Dar es Salaam, there are a large number of microfinance institutions available to residents, including, for those who quality, large commercial banks that offer microfinance services. One of the largest microfinance institution (MFI) service providers is BRAC-­‐Tanzania with 116,749 active borrowers in 2011. The average loan per borrower is 176 USD, with a range of loans available between 800 USD and 5000 USD to groups of (predominately women) borrowers between 15-­‐ 30 members3. Loans are typically put towards enterprises including beauty parlours, tailoring, restaurants and grocery stores in the formal and informal sector (MixMarket, 2012). This is aggregate data and was not available for Dar es Salaam alone. A relatively new development in Tanzanian banking is mobile phone banking which has generated more than 20 million customers. Vodaphone has taken a lead role in this area. Governance & structure of local government ĂƌĞƐ^ĂůĂĂŵŝƐŽŶĞŽĨϮϲĂĚŵŝŶŝƐƚƌĂƚŝǀĞƌĞŐŝŽŶƐŝŶdĂŶnjĂŶŝĂ͘dŚĞĐŝƚLJ͛ƐĂĚŵŝŶŝƐƚƌĂƚŝǀĞƐƚƌƵĐƚƵƌĞ comprises three municipalities and a City Council headed by the Mayor (currently Dr. Didas Massaburi, elected in 2010). The Mayor is elected from 20 councillors who form the City Council. Councillors and mayors are elected every five years. There is no limit on the number of times an individual can be elected to office. The City Council has a coordinating role with regards to the three municipalities: Kinondoni, Ilala and Temeke. The Council coordinates infrastructure related functions of the municipalities and facilitates cooperation between them and other local government actors. The Council is also responsible for key issues that cut across all three municipalities such as city-­‐wide transport, health services and fire and emergency services. For city administration, the three municipalities are further divided into 10 Divisions, which are then divided into 73 Wards represented by Ward Councillors. WarĚƐĂƌĞĚŝǀŝĚĞĚŝŶƚŽ^ƚƌĞĞƚƐŽƌ͚DŝƚĂĂ͕͛ the smallest unit of administration in Dar es Salaam. Each Ward has a Ward Development Committee. There are seven electoral constituencies in Dar es Salaam and each constituency elects a Member of Parliament (MP) who serves a five-­‐year term. Environment & Ecology The city is broadly divided into three ecological zones: the upland zone is the hilly areas west and north of the city; the middle plateau; and the low lands south of the city. The whole city is vulnerable to rises in sea level. Poor infrastructure including barriers and flood defence, have a 3 BRAC ʹ dĂŶnjĂŶŝĂ;ϮϬϭϮͿ͕͚dĂŶnjĂŶŝĂ͗DŝĐƌŽĨŝŶĂŶĐĞ͕͛ǁǁǁhttp://www.brac.net/content/where-­‐we-­‐work-­‐tanzania-­‐ microfinance (accessed 05/09/12). 8 particularly devastating effect on residents of informal settlements whose very homes and their location increase their susceptibility to the damage caused by heavy rain and other climate related activity. ACTOR GROUPS You form part of one of eight actor groups for which a brief narrative is provided below. Each actor group will be given a separate confidential brief when arriving at Cumberland Lodge. 1. Residents from Temeke District/Kurasini Ward, Chamazi This group of residents is made up of a heterogeneous group of actors who are all affected by plans ƚŽĞdžƉĂŶĚĂƌĞƐ^ĂůĂĂŵ͛ƐŵĂŝŶƉŽƌƚ͘dŚĞƉŽƌƚĞdžƉĂŶƐŝŽŶƉůĂŶ affects about 36,000 residents. Three-­‐ quarters of them are tenants who rent the structures they live in. In October 2007, the first wave of 2,000 evictees (600 households consisting of structure owners and tenants) from Kurasini were forcibly ordered to leave their homes in preparation for large-­‐scale demolitions. In keeping with Tanzanian practice, only structure owners -­‐ who account for approximately 40% of the population -­‐ received compensation upon eviction for lost property while tenants received none. In response, 300 tenant families organised under the auspices of the Tanzania Federation of the Urban Poor (TFUP) to save enough money to be able buy a plot of land in Chamazi Ward. The Housing Cooperative formed by TFUP has so far constructed 42 homes, installed a solar powered bore hole, water points and a sewerage system and has plans to develop further housing and facilities. These plans include the formation of a Housing Association to build and manage a stock of rental units for new residents. 2. Finance Institutions The Financial system in Tanzania includes formal financial agencies such as commercial banks and micro-­‐finance institutions (MFIs) and informal organisations that are virtually outside the control of the established legal framework. Informal financial institutions include moneylenders and rotating savings and credit associations such as Merry-­‐Go-­‐Rounds, which have a long history in Tanzania. Increasingly new forms of financial organisation are emerging, such as community savings and loan groups , new Mobile Banking systems using cell phone technology (Laugtug in Ishengoma, 2011), and ĂŶĞǁĂŐĞŶĐLJĐĂůůĞĚd&^h&ǁŚŝĐŚĂŝŵƐƚŽŚĞůƉŝŶŐĐŽŶǀĞŶƚŝŽŶĂůůLJ͞ŶŽŶ-­‐ďĂŶŬĂďůĞ͟ƉƌŽũĞĐƚƐƚŽĂĐĐĞƐƐ capital funds. Actors in this actor group will therefore represent the formal and informal financial sectors. 3. International Agencies International Development Assistance to Tanzania plays a significant role in supporting national efforts on poverty reduction and development, as well as government development expenditure. Aid funds accounted for approximately 40% of the national and 80% of the development budget ;DŝŶŝƐƚƌLJŽĨ&ŝŶĂŶĐĞĂŶĚĐŽŶŽŵŝĐĨĨĂŝƌƐ͕ϮϬϭϬͿ͘^ŽŵĞŬĞLJƉĂƌƚŶĞƌƐƚŚĂƚĐŽŶƚƌŝďƵƚĞƚŽdĂŶnjĂŶŝĂ͛Ɛ general budget support include China, the African Development Bank, Canada, Denmark, European Commission, Finland, Ireland, Japan, Germany, Netherland, Norway, Sweden, Switzerland, United Kingdom and the World Bank. The aid effectiveness agenda in Tanzania has been at the centre of the development debate since the mid 1990s. Many of the AID agencies try to co-­‐ordinate their AID inputs in line with the local Poverty Reduction Strategy Plan. dŽĚĂƚĞ͕ƚŚĞƌĞŝƐŶŽƐŝŐŶŽĨƚŚĞĐŽƵŶƚƌLJ͛Ɛ aid dependency decreasing anytime soon and the focus now is on aid effectiveness, harmonisation and alignment with development priorities. 4. State Authorities A range of State actors are individually responsible for land, housing and human settlements, water and sewerage supply, public transport infrastructure, international and domestic sea trade, ƉƌŽƚĞĐƚŝŽŶŽĨǁŽŵĞŶĂŶĚĐŚŝůĚƌĞŶ͛ƐƌŝŐŚƚƐ͕ŵĂŶĂŐĞŵĞŶƚŽĨ financial affairs and budgeting, 9 coordinating and financing the development of State-­‐owned infrastructure, and disaster ŵĂŶĂŐĞŵĞŶƚ͘ĂĐŚ^ƚĂƚĞĂĐƚŽƌŚĂƐŝŵƉŽƌƚĂŶƚƌŽůĞƐƚŽƉůĂLJŝŶƚŚĞĐŽƵŶƚƌLJ͛ƐĚĞǀĞůŽƉŵĞŶƚĞĨĨŽƌƚƐƚŽ improve the quality of life of the poŽƌ͕ĂŶĚƚŚĞLJŵƵƚƵĂůůLJƌĞŝŶĨŽƌĐĞĞĂĐŚŽƚŚĞƌ͛ƐǁŽƌŬ͘^ƚĂƚĞ Government widely acknowledges its struggle with many challenges, among others, lack of resources and capacity. The government is unfortunately afflicted by persistent allegations of misappropriation of funds and misconduct. 5. Residents from Tandale and Magomeni Districts of Kinondoni Ward, Kinondoni Due to its location, the Kinondoni District is at risk of frequent flooding. The Kinondoni Ward is one of the fastest growing settlements within the wider Kinondoni District and region, despite its vulnerability to flooding. In December 2011, Kinondoni Ward was devastated by a three-­‐day flash flooding event that affected over 50,000 people, mostly living in low lying areas that had long been condemned by the government due to sea level rise and climate change vulnerabilities. As a result, many people have lost their entire livelihoods. While the government treated the problem as a natural disaster, there is growing evidence that the floods could have been prevented if effective disaster risk management systems were in place. 6. Organised Civil Society NGOs represent a wide variety of organisational arrangements, including faith-­‐based, charitable, relief and development organisations registered as NGOs in Tanzania. Although each organisation has a specific agenda, they all work towards poverty reduction, improving the lives of vulnerable communities and specifically women and children. Civil society organisations are seen as vital development partners and their activities are widely supported in Tanzania. The National Population Policy highlights, as one of its achievements, the increased number of NGOs and CBOs engaged the development process. However, some government representatives ʹ in particular at the local level ʹ are hesitant and sometimes even averse to the involvement of civil society organisations in development processes, and often criticize them for being top-­‐down organisations led by elites, serving their own interests. 7. Local Government Local Governments, including Municipalities, assists the State Government to achieve its development objectives. Local Government in Tanzania, as in all other countries, is expected to provide essential public services, to ensure safety and security and to promote local economic development. Local Government can have a comparative advantage over State Government because it has a functional role within communities. >ŽĐĂů'ŽǀĞƌŶŵĞŶƚ͛Ɛ mandate for decision-­‐making and for the control of resources is expanding in Tanzania due to ongoing decentralisation reforms. However, areas of public service delivery, that should be the responsibility of local government, are often still retained and discharged by State Government. Local government is faced with the ongoing and escalating development challenges of widespread and pervasive poverty, lack of housing and security of tenure, inadequate basic infrastructure and a high population growth rate. 8. Private Sector Tanzania has been promoting the private sector for over 20 years as it transformed from a socialist, controlled economy to a market economy. Tanzania is considered to now have one of the most liberal investment regimes in Africa. As a result, it attracts a lot of foreign investment, for example APM Terminals, the second biggest port operator in the world, who expressed strong interest in investing in modernising and extending Dar es Salaam Port, working alongside Hong Kong-­‐based Hutchison Port Holdings. Foreign investors from countries such as China and Dubai are encouraged by the Tanzanian government to finance and manage new industry and infrastructure. 10 Tanzania also has a rapidly growing informal business sector. It is estimated that 55% of total households in Dar es Salaam are engaged in informal sector activities at any time of the year (SIDA, 2004). dĂŶnjĂŶŝĂ͛Ɛ informal sector consists mainly of unregistered and hard-­‐to tax groups such as small scale traders, farmers, small manufacturers, craftsmen, individual professionals and many small-­‐scale businesses. WORKSHOP ACTIVITIES Workshop participants will be involved in a sequence of activities that begin in London, develop in Windsor and conclude in London. You should view these activities in conjunction with the Workshop Programme. Group Work 1 ʹ Diagnosis of Motivations and Interests Activities related to Group Work 1 begin in London on Monday 22 October and conclude with a presentation on Sunday 28 October for Wave 1 and Tuesday 30 October for Wave 2. Working in your actor groups, please undertake the following: 1. Review the various sub-­‐actors within your actor group. 2. Identify the key motivations and interests of each sub-­‐actor group (note: these may overlap between sub-­‐actor groups and so where it makes sense to band some sub-­‐actors together you should do so). To complete this task you will have to undertake additional research. 3. Collate the key motivations and interests of sub-­‐actor groups and agree on THREE criteria that reflect the key interests for the whole actor group within a framework of equitable land use planning and affordable settlement development. 4. Transfer these criteria onto a large sheet of paper, ready to present at Group Work 1 at Cumberland Lodge. 5. Identify a set of questions in relation to issues you are not clear about with respect to your set of actors. These may include the relationships between your actor group and other actors. Be ready to present these questions at Group Work 1, Cumberland Lodge. Your actor group will have 10 minutes to report back and 5 minutes for Q&A at Group Work 1 in Cumberland Lodge. Group Work 2 ʹ Applying the Web of Institutionalization to assess the constraints and potential for sustainable and equitable city development This activity takes place on Monday 29 October for Wave 1 and Tuesday 30 October for Wave 2. For this exercise you are representing the interests of your actor group. In each break-­‐out room you are all divided into four sub-­‐groups, each addressing one of four spheres of the web: Citizen Sphere, Policy Sphere, Organisational Sphere and Delivery Sphere. For the sphere allocated to your sub-­‐ group, please complete the following tasks: 1. Identify the problems and opportunities associated with the elements and their inter-­‐relations in the sphere. You should specify whose problem or opportunity it is when recording these (i.e. which actor group). 2. Where there is insufficient information, identify the missing data and define this as a problem. 3. Record problems (pink card) and opportunities (green card) for reporting back. Remember, you are representing your actor group. Following this exercise return together in your actor groups. Back in your actor groups, you should report back on your element of the sphere. 11 1. In your actor group, place the cards next to the appropriate elements in your sphere of the web so that your actor group is thoroughly diagnosed. 2. Share your findings with others in your group. Group Work 3ʹ Recommendations of your Actors Group This activity takes place on Monday 29 October for Wave 1 and Wednesday 31 October for Wave 2. Working in your actor groups, and drawing on your diagnosis from the previous session, develop THREE recommendations to advance the interests of your actor group within a framework of equitable land use planning and affordable settlement. Please undertake the following tasks to do this: 1. Identify the elements, or links between elements, that you think need to be strengthened in order to develop a strategy for equitable land use planning and affordable settlement. In doing this, you should identify the specific problems and opportunities you want to prioritise. 2. Make up to three recommendations for the actor group you are representing (where it makes sense to group sub-­‐actors together you should do so). 3. Clearly assess these recommendations in terms of the three criteria you defined at the beginning of the workshop (Group Work 1) and ensure that they address the problems and utilise the opportunities you prioritised in your diagnosis. 4. Working in smaller sub-­‐groups, develop a strategy for each recommendation (one per sub-­‐group) ʹ this strategy should identify who to involve to enact the recommendation, what resources are needed and over what time frame. By the end of the session this sub-­‐group should be well versed in one of the recommendations to be put forward by the group. 5. Report back to the group. Group Work 4 ʹ Negotiation and Refinement of Recommendations Activities related to Group Work 4 begin at Cumberland Lodge on Tuesday 30 October for Wave 1 and Wednesday 31 October for Wave 2. Activities continue for both waves on Thursday 1 November and conclude with a presentation by each actor group. In your actor groups, develop an appropriate strategy to negotiate the interests of your actor group to others. Decide, based on the recommendations you developed in the previous session, which stakeholders present at Cumberland Lodge and in the other Wave you would like to talk to in order to advance your recommendations, determine what you need from them and what you can offer, and then decide what stakeholder meetings you will attend (there will be a separate notice on stakeholder meetings). To do this, you should undertake the following tasks: 1. Define a negotiating strategy to engage with the other actor groups. This strategy should identify what issues need to be negotiated, with whom and by whom in your group. The strategy will be implemented in two stages, the first at Cumberland Lodge, and the second back in London on Thursday 1 November between 10.00 and 11.00 am. 2. Stakeholder meetings at Cumberland Lodge will begin at 9.45 am for Wave 1 and at 14:30 for Wave 2. 3. Remember to bring your work so far to Group Work 4 (continued) in London. On your return to London, at 10am on 1 November, start negotiations based on your negotiating strategy. You should send small groups of delegates to meet up with other actor groups. On the basis of your negotiations, at around 11.00am, refine your recommendations for presentation to the plenary at 11:30am. At the plenary, each actor group will be called upon to present and clarify their recommendations, and to explain how they are going to implement them on the basis of negotiations with the other actors. 12 BIBLIOGRAPHY General Readings Tanzania x x x x x x ,ĞŝůŵĂŶ͕ƌƵĐĞĂŶĚWĂƵů<ĂŝƐĞƌ;ϮϬϬϮͿ͕͚ZĞůŝŐŝŽŶ͕/ĚĞŶƚŝƚLJĂŶĚWŽůŝƚŝĐƐŝŶdĂŶnjĂŶŝĂ͕͛ Third World Quarterly, 23(4):691-­‐709. DŝdžDĂƌŬĞƚ ;ϮϬϭϮͿ͕ ͚DŝĐƌŽĨŝŶĂŶĐĞ ŝŶ dĂŶnjĂŶŝĂ͗ ŽƵŶƚƌLJ WƌŽĨŝůĞ͕͛ ǁǁǁ http://www.mixmarket.org/mfi/country/Tanzania (accessed 05/09/12). Nnkya T. and J. Lupala (2008), ͚ZĞǀŝĞǁŽĨWůĂŶŶŝŶŐĚƵĐĂƚŝŽŶĂƚ^ĐŚŽŽůŽĨhƌďĂŶĂŶĚZĞŐŝŽŶĂůWůĂŶŶŝŶŐ͕ Ardhi University, Dar Es Salaam͕͛ WĂƉĞƌ ƉƌĞƉĂƌĞĚ ĨŽƌ ƚŚĞ tŽƌŬƐŚŽƉ ŽŶ ƚŚĞ ZĞǀŝƚĂůŝnjĂƚŝŽŶ ŽĨ WůĂŶŶŝŶŐ Education in Africa, 13-­‐15 October, Cape Town. Tanzania National Bureau of Statistics (2009), Household Budget Survey 2007 ʹ Tanzania Mainland, National Bureau of Statistics, United Republic of Tanzania. United Republic of Tanzania (2002), Housing and Population Census: Analytical Report, Volume X, National Bureau of Statistics/Ministry of Planning, Economy and Empowerment, National Bureau of Statistics, United Republic of Tanzania, August 2006. United Republic of Tanzania (2000), National Micro-­‐Finance Policy, Ministry of Finance, United Republic of Tanzania, May 2000. General readings Dar es Salaam x x x x x Brennan, James and Andrew Burton (2007), 'The emerging metropolis: a short history of Dar es Salaam, circa 1862-­‐2005.', in Brennan, Burton and Lawi (eds.), Dar es Salaam: Histories from an emerging African metropolis, Dar es Salaam/Nairobi: Mkukina Nyota/ British Institute in Eastern Africa, pp. 13-­‐75. ŽLJůĞ͕ :ŽĞ ;ϮϬϭϮͿ͕ ͚Ăƌ ĞƐ ^ĂůĂĂŵ͗ ĨƌŝĐĂ͛Ɛ ŶĞdžƚ ŵĞŐĂĐŝƚLJ͍͕͛ EĞǁƐ ŽŶůŝŶĞ͕ ϯϭ :ƵůLJ ϮϬϭϮ ǁǁǁ http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/magazine-­‐18655647 (accessed 16/08/12). ĂƌĞƐ^ĂůĂĂŵŝƚLJŽƵŶĐŝů;ϮϬϬϰͿ͕͚ĂƌĞƐ^ĂůĂĂŵŝƚLJWƌŽĨŝůĞ͕͛EŽǀĞŵďĞƌϮϬϬϰ. DƚĂŶŝ͕͘;ϮϬϬϰͿ͕͚'ŽǀĞƌŶĂŶĐĞŚĂůůĞŶŐĞƐĂŶĚŽĂůŝƚŝŽŶƵŝůĚŝŶŐŵŽŶŐhƌďĂŶŶǀŝƌŽŶŵĞŶƚĂů^ƚĂŬĞŚŽůĚĞƌƐ ŝŶĂƌĞƐ^ĂůĂĂŵ͕dĂŶnjĂŶŝĂ͕͛Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, Vol. 1023, Issue 1, pp.300-­‐307. hE,/dd;ϮϬϭϬͿ͚ŝƚLJǁŝĚĞĐƚŝŽŶWůĂŶĨŽƌhƉŐƌĂĚŝŶŐhŶƉůĂŶŶĞĚĂŶĚhŶƐĞƌǀŝĐĞĚ^ĞƚƚůĞŵĞŶƚƐŝŶĂƌĞƐ ^ĂůĂĂŵ͕͛EĂŝƌŽďŝ͗hE,/dd. Land x x x <ŽŵďĞ͕tŝůůĂƌĚ;ϮϬϭϬͿ͕͚>ĂŶĚŽŶĨůŝĐƚƐŝŶĂƌĞƐ^ĂůĂĂŵ͗tŚŽ'ĂŝŶƐ͍tŚŽ>ŽƐĞƐ͍͕͛tŽƌŬŝŶŐWĂƉĞƌEŽ͘ϴϮ͕ Crisis States Working Papers Series No.2, LSE Development Studies Institute. ^ƵŶĚĞƚ͕'Ğŝƌ;ϮϬϬϲͿ͕͚dŚĞĨŽƌŵĂůŝƐĂƚŝŽŶƉƌŽĐĞƐƐŝŶdĂŶnjĂŶŝĂ͗/ƐŝƚĞŵƉŽǁĞƌŝŶŐƚŚĞƉŽŽƌ͍͕͛WƌĞƉĂƌĞĚĨŽƌƚŚĞ Norwegian Embassy in Tanzania [www] http://www.statkart.no/filestore/Eiendomsdivisjonen/PropertyCentre/Pdf/theformalisationprocessintanza nia_301008.pdf (accessed 04/09/12). United Republic of Tanzania (1997), National Land Policy (second edition), Ministry of Lands and Human Settlements Development, United Republic of Tanzania. Port Development x x x ,ŽLJůĞ͘;ϮϬϬϬͿ͕͚'ůŽďĂůĂŶĚůŽĐĂůĨŽƌĐĞƐŝŶĚĞǀĞůŽƉŝŶŐĐŽƵŶƚƌŝĞƐ͕͛Journal for Maritime Research, 2(1):9-­‐27. Tanzania Ports Authority (2011), ͚Development Program Project Brief͛;ƵŶƉƵďůŝƐŚĞĚƌĞƉŽƌƚͿ Tanzania Ports Authority (2009Ϳ͕ ͚dĂŶnjĂŶŝĂ WŽƌƚƐ ƵƚŚŽƌŝty Annual Report & Accounts͛, [Online]: http://www.tanzaniaports.com/index.php?option=com_docman&task=doc_download&gid=60&Itemid=22 9 (accessed 18/10/12). Flood vulnerability in Dar es Salaam x x Dar es Salaam City Council TANZANIA (2011), ͚Building a Safe and Climate Resilient City ;WƌĞƐĞŶƚĂƚŝŽŶͿ͕͛ [Online] http://locs4africa.iclei.org/files/2011/03/Hon-­‐Mayor-­‐Didas-­‐Masaburi_Dar-­‐es-­‐Salaam-­‐City-­‐ Council.pdf (accessed 18/10/12). John, R. (n.d.), ͚Urban Participatory Climate Change Adaptation Appraisal Methodology, Social Vulnerability, Institutions and Governance͕͛ presentation at Ardhi University, Dar es Salaam. 13 x ^dZd^ĞĐƌĞƚĂƌŝĂƚ;ϮϬϭϭͿ͕͚hƌďĂŶWŽǀĞƌƚLJĂŶĚůŝŵĂƚĞŚĂŶŐĞŝŶĂƌĞƐ^ĂůĂĂŵ͕dĂŶnjĂŶŝĂ͗ĂƐĞ^ƚƵĚLJ͕͛ final report prepared by the Pan-­‐African START Secretariat, International START Secretariat, Tanzania Meteorological Agency and Ardhi University, Tanzania, March 2011. Group-­‐specific Bibliography and Web Links Slum/Shack Dwellers from Temeke District/Kurasini Ward, Chamazi x x x x HI, CCI, TFUP (2012), ͚Chamazi Resettlement Project, ĂƌĞƐ^ĂůĂĂŵ͕dĂŶnjĂŶŝĂ͕͛KŶůŝŶĞ http://policy.rutgers.edu/academics/projects/portfolios/tanzaniaSp12.pdf (accessed 18/10/12). ,ŽŽƉĞƌD͘ĂŶĚ>͘KƌƚŽůĂŶŽ;ϮϬϭϮͿ͕͚DŽďŝůŝƐĂƚŝŽŶŝŶ<ƵƌĂƐŝŶŝ͕͛Environment and Urbanization, 24(1):99ʹ114. Clemence S. Mero, MLHHSD (2011), ¶Kurasini Area Redevelopment Plan͛, [Online] http://www.visual.se/pics/PDFs/kurasini_area_redevelopment_plan_c_mero.pdf (accessed 18/10/12). Mwanakombo Mkanga (2010), Impacts of Development-­‐Induced Displacement on Households Livelihoods: Experience of people from Kurasini, Dar es Salaam ʹ Tanzania. Unpublished Masters Thesis Slum/Shack Dwellers from Tandale and and Magomeni Districts, Kinondoni Ward, Kinondoni x x x Hooper M. (2008), Motivating Urban Social Movement Participation: Lessons from Slum Dweller DŽďŝůŝnjĂƚŝŽŶ ŝŶ <ƵƌĂƐŝŶŝ͕ Ăƌ Ɛ ^ĂůĂĂŵ͕͛ conference paper Development Studies Association (DSA) Conference London November 2008 Kinondoni Municipal Council, [www] http://www.kinondonimc.go.tz (accessed 18/10/12) Mbonile M. and J. Kivelia, ͚Population, Environment and Development in Kinondoni District, Tanzania͛ [Online] http://www.gla.ac.uk/media/media_42372_en.pdf (accessed 18/10/12) Organised Civil Society x x x Aga Khan Development Network (2007), ͚The Third Sector in Tanzania ʹ Learning more about Civil Society Organizations, Their Capabilities and Challenges͛KŶůŝŶĞ http://www.akdn.org/publications/civil_society_tanzania_third_sector.pdf (accessed accessed 18/10/12). Michael Jennings (2008), Surrogates of the State: NGOs, Development and Ujamaa in Tanzania, Kumarian Press. Research on Poverty Alleviation, Tanzania (2007), ͚Tanzanian Non-­‐Governmental Organisations -­‐ Their Perceptions of Their Relationships with the Government of Tanzania and Donors, and Their Role in Poverty Reduction and Development͕^ƉĞĐŝĂůWĂƉĞƌϬϳ͘Ϯϭ͛, [Online] http://www.repoa.or.tz/documents_storage/Research%20Activities/Special_Paper_07.21.pdf (accessed 18/10/12). State Authorities x x x x x x Government of Tanzania (2005), ͚Country Report on The Implementation of the Beijing Platform for Action and the Outcome Document of the Twenty-­‐third Special Session of the General Assembly ʹ Beijing +10͕͛ [Online] http://www.un.org/womenwatch/daw/Review/responses/UNITEDREPUBLICOFTANZANIA-­‐ English.pdf (accessed 18/10/2012). Government of Tanzania, Planning Commission, ͚Tanzania Development Vision 2025͕͛KŶůŝŶĞ http://www.tanzania.go.tz/pdf/theTanzaniadevelopmentvision.pdf (accessed 18/10/12). Government of Tanzania (2008), ͚Resettlement Policy Framework͕͛ [Online]http://www.nlupc.org/images/uploads/2008-­‐12-­‐ 29_resettlement_policy_framework_oct_2008.pdf (accessed 18/10/12). Wakuru Magigi, B.B.K.Majani ;ϮϬϬϱͿ͕͚WůĂŶŶŝŶŐ^ƚĂŶĚĂƌĚƐĨŽƌhƌďĂŶ>ĂŶĚhƐĞWůĂŶŶŝŶŐĨŽƌĨĨĞĐƚŝǀĞ>ĂŶĚ Management in Tanzania: An Analytical Framework for Its Adoptability in Infrastructure Provisioning in /ŶĨŽƌŵĂů^ĞƚƚůĞŵĞŶƚƐ͕͛&ƌŽŵWŚĂƌĂŽŚƐƚŽ'ĞŽŝŶĨŽƌŵĂƚŝĐƐ&/'tŽƌŬŝŶŐtĞĞŬϮϬϬϱand GSD-­‐8, Cairo, Egypt April 16-­‐21, 2005. [Online] http://www.fig.net/pub/cairo/papers/ts_19/ts19_03_magigi_majani.pdf (accessed 18/10/12). Kawambwa S. J., Transport Infrastructure Constraints: Challenges and Opportunities for Private Sector Participation, Public Statement. Kiunsi R. et al (2009), ͢Mainstreaming Disaster Risk Reduction in Urban Planning Practice in Tanzania͛,[Online] 14 x x x x x x http://www.preventionweb.net/files/13524_TANZANIAFINALREPORT27OCT09Mainstrea.pdf (accessed 18/10/12) Office of the Prime Minister (2010), ͚National progress report on the implementation of the Hyogo Framework for Action (2009-­‐2011)͕͛ [Online] http://www.preventionweb.net/files/16232_tza_NationalHFAprogress_2009-­‐11.pdf (accessed 18/10/12). Ministry of Community Development, Gender and Children (2010),͛ Achievement of the Millennium ĞǀĞůŽƉŵĞŶƚ'ŽĂůƐ͕͛ [Online] http://www.ohchr.org/Documents/Issues/EPoverty/socialprotection/Tanzania.pdf (accessed 18/10/12). ůĂƐŝ͘͘^ĞůĞŬŝ͕͚Urban Housing Problems in Tanzania͕͛D>,,^͕KŶůŝŶĞ http://www.lth.se/fileadmin/hdm/alumni/papers/ad2001/ad2001-­‐18.pdf (accessed 18/10/12). Charles Mapima͕͚The Role of Education Tanzania Education Authority in Supplementing The Government Effort in Improving Quality of Education in Tanzania͕͛dĂŶnjĂŶŝĂĚƵĐĂƚŝŽŶƵƚŚŽƌŝƚLJ͕Knline] http://www.ncc.or.tz/rte.pdf (accessed 18/10/12). Tanzania Poverty Reduction Strategy Plan (2000), [Online] http://www.tanzania.go.tz/images/prsp.pdf (accessed 18/10/12) Tanzania Poverty Reduction Strategy Plan annual implementation report (2008), [Online] http://www.fao.org/righttofood/inaction/countrylist/Tanzania/Tanzania_PRSP_ProgressReport_2007.pdf (accessed 18/10/12). Local Government x x x Local Government System in Tanzania (2006), [Online] http://www.tampere.fi/tiedostot/5nCY6QHaV/kuntajarjestelma_tansania.pdf (accessed 18/10/2012). Liviga. ͘:͘;ϮϬϬϴͿ͕͚>ŽĐĂů'ŽǀĞƌŶŵĞŶƚŝŶdĂŶnjĂŶŝĂ͗WĂƌƚŶĞƌŝŶĞǀĞůŽƉŵĞŶƚ or Administrative Agent of the ĞŶƚƌĂů'ŽǀĞƌŶŵĞŶƚ͍͕͛Local Government Studies, 18(3):208-­‐225. Venugopal V. & ^͘zŝůŵĂnj;ϮϬϭϬͿ͕͚ĞĐĞŶƚƌĂůŝnjĂƚŝŽŶŝŶdĂŶnjĂŶŝĂ͗ŶƐƐĞƐƐŵĞŶƚŽĨ>ŽĐĂů'ŽǀĞƌŶŵĞŶƚ ŝƐĐƌĞƚŝŽŶĂŶĚĐĐŽƵŶƚĂďŝůŝƚLJ͕͛Public Administration and Development, 30(3):215-­‐231. Private Sector x x x tĂƚĞƌŝĚ͕͚Private Sector Participation in Dar es Salam, Tanzania͕͛KŶůŝŶĞ http://www.ucl.ac.uk/dpu-­‐ projects/drivers_urb_change/urb_infrastructure/pdf_public_private_services/W_WaterAid-­‐ PRS_Dar_es_Salaam_Tanzania.pdf (accesed 18/10/2012). Kaseva D͘ĂŶĚ^͘͘DďƵůŝŐǁĞ;ϮϬϬϱͿ͕͚ƉƉƌĂŝƐĂůŽĨƐŽůŝĚǁĂƐƚĞĐŽůůĞĐƚŝŽŶĨŽůůŽǁŝŶŐƉƌŝǀĂƚĞƐĞĐƚŽƌ ŝŶǀŽůǀĞŵĞŶƚŝŶĂƌĞƐ^ĂůĂĂŵĐŝƚLJ͕dĂŶnjĂŶŝĂ͕͛Habitat International, Vol. 29, pp. 353ʹ366. dŚĞƌŬŝůĚƐĞŶK͘;ϮϬϬϬͿ͕͚WƵďůŝĐ^ĞĐƚŽƌZĞĨŽƌŵŝŶĂWŽŽƌŝĚ-­‐Dependant Country, Tanzania, Public Administration & Development, Vol. 20, pp. 61-­‐71. Finance Institutions x x x x ILO, UNDP, UNIDO (2002), ͚Roadmap Study of the Informal ^ĞĐƚŽƌŝŶDĂŝŶůĂŶĚdĂŶnjĂŶŝĂ͕͛KŶline] http://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/@ed_emp/@emp_policy/@invest/documents/publication/wc ms_asist_8365.pdf (accessed 18/10/12). Ishengoma Anitha (2011), ͚Analysis of Mobile Banking for Inclusion in Tanzania: Case of Kibaha District Council͛͘ Mwakaje Agnes (2010),͛Gender, Poverty and Access to Socio-­‐Economic Services in Un-­‐Planned and Un-­‐ Services Urban Areas of Dar es Salaam, Tanzania͛, Journal of Sustainable Development in Africa, Vol. 12, No. 3, pp. 204-­‐221. White Simon (2010), ͚Synthesis Report of Key Investment Climate and Business Environment assessments in Tanzania͛, Southern African IDEAS (Pty.) Ltd. [Online] http://www.tzdpg.or.tz/uploads/media/Synthesis_Report_IC-­‐BE_Tza_2010.pdf (accessed 10/09/12) International Agencies x Oden B. and Tilles T (2003), ͚Tanzania: new aid modalities and donor harmonisation͛, Published by Norad. 15 x x Deutcher E. and Fyson S. (2008), ͚Improving the effectiveness of aid͛, Finance and Development, September 2008. [Online] http://www.perjacobsson.org/external/pubs/ft/fandd/2008/09/pdf/deutscher.pdf (accessed 18/10/12). Helleiner G. K. et al (1995), ͚Report of the Group of Independent Advisers on Development Cooperation Issues Between Tanzania and its Aid Donors͛, Danish Ministry of Foreign Affairs. WEB SITES INTERNATIONAL http://citiesalliance.org http://www.unhabitat.org/publications/ http://worldbank.org TANZANIAN GOVERNMENT Dar es Salaam Water and Sewerage Corporation (DAWASCO) http://www.dawasco.com/ Disaster Preparedness http://www.meteo.go.tz/ Ministry of Community Development, Gender and Children http://www.mcdgc.go.tz/ Ministry of Finance http://www.mof.go.tz/ Ministry of Lands and Human Settlements Development http://www.ardhi.go.tz/ Ministry of Regional Administration and Local Government http://www.pmoralg.go.tz/ Ministry of Transport http://www.mot.go.tz/ Ministry of Works http://www.mow.go.tz/ Poverty Monitoring http://www.povertymonitoring.go.tz/ Tanzania Ports Authority http://www.tanzaniaports.com/ CIVIL SOCIETY Centre for Community Initiatives http://www.cci.or.tz/ Homeless International http://www.homeless-­‐international.org/our-­‐work/where-­‐we-­‐work/tanzania Paradigm Housing Association-­‐ http://www.paradigmhousing.co.uk/about-­‐us Rooftops ABRI international http://rooftops.digcanada.com Slum/Shack Dwellers International http://www.sdinet.org/about-­‐what-­‐we-­‐do/ 16