Practitioner’s Perspective NEW MODEL PRIVACY NOTICE (for Gramm Leach Bliley Act

Guide to Computer Law—Number 338

Practitioner’s Perspective

by Holly K. Towle, J.D.

Holly K. Towle is a partner with K & L Gates fi

LLP, an international law rm, and chair of the fi rm’s E-merging

Commerce group. Holly is located in the fi rm’s

Seattle offi ce and is the coauthor of The Law of Electronic Commercial Transactions (2003,

A.S. Pratt & Sons). Holly.Towle@KLgates.com,

206-623-7580.

NEW MODEL PRIVACY NOTICE

(for Gramm Leach Bliley Act fi nancial institutions)

In 1999, Congress enacted the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act (GLBA) 1 which governs the handling of customer’s nonpublic, personal information by

“fi nancial institutions,” a misleading term encompassing a wide range of companies—from car dealers, tax planners, broker dealers, insurance companies, and so on—to traditional banks. A decade later, what could be new about the GLBA? This:

Practitioner’s Perspective appears periodically in the monthly Report Letter of the CCH Guide to

Computer Law. Various practitioners provideindepth analyses of signifi cant issues and trends.

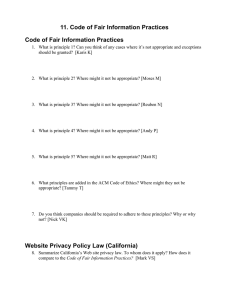

This is the fi rst page of a new, two-page, optional model form for use by

GLBA fi nancial institutions. At least for purposes of obtaining the safe harbor it affords, its format and content cannot be altered. Answers and

CCH G

UIDE TO

C

OMPUTER

L

AW

N

UMBER

338 designated information can be added but only in accordance with strict form instructions; further text is not allowed.

The good news is that for fi nancial institutions with privacy regimes that work in this rigid format, use of the form provides a safe harbor for compliance with the heart of GLBA disclosure rules. The bad news is that many institutions will not be able to use the form at all, or with text that would qualify for the safe harbor. Worse news is that the existing safe harbor achieved by use of sample clauses provided in

GLBA regulations (or SEC guidance) is being eliminated.

The only safe harbor left will be through prescribed use of the model form. Given that, some basic information about the model may be helpful.

Why Now?

Endeavors to comply with the GLBA over the years led to complaints that privacy notices were too lengthy, dense, and hard to understand—which resulted in exploration of a “simple” model form approach. Those who have tried to draft any form of privacy notice will see the irony in that effort. Particularly outside of GLBA, privacy policy providers learned early that simple, understandable short statements like “We do not share your information” were suicidal. Although that kind of statement conveyed the intended message for a company that does not sell or share customer lists, it was too simple to be accurate under data protection “unfair or deceptive acts” principles because information is always shared for some reason. That some sharing obviously must and will occur goes without saying, but such truths are not part of data protection law compliance and regulatory enforcement actions 2 were quick to point that out. Thus began the long march of companies towards ever longer and denser privacy policies in an effort to avoid deception ( e.g

., “We do not share your information

. . .[and on into lengthy oblivion]”). except that we do share it with our service providers, including, without limitation, in a merger, consolidation, or sale of substantially all of our assets, in a bankruptcy, for authentication and fraud prevention purposes, when the law requires us to do so, and

Even though GLBA regulations actually allow much simpler privacy statements than other data protection regimes, the

Financial Services Regulatory Relief Act of 2006 amended the GLBA to require the GLBA agencies to create an optional, simple model form that consumers could easily understand and included a safe harbor for GLBA fi nancial institutions.

3

In November 2009, eight GLBA regulators 4 released a fi nal model form.

5 Not surprisingly, they could not meet the statutory directive for simplicity while also being accurate, nor could they accommodate the actual complexity of relevant laws. Nevertheless, the form creates a safe harbor of sorts. Because the model form does not cover some legal complexities and assumes selective default rules, it also can be characterized as more of an unsafe safe harbor— i.e

., it should be used warily and only after review of what it actually does and what it might not do.

Sea Change. Even though use of the model is optional, it effects a sea change in GLBA compliance. This is because the amended regulations remove—after a transition period ending December 31, 2010—the safe harbor for use of existing sample clauses initially included in the appendices of the

GLBA privacy regulation (or SEC guidance). The effective date of the fi nal regulation is December 31, 2009 and the model form may be used as of that date, but some amendments are not effective until 2012.

6 Those choosing not to use the model form can continue to rely on the sample clauses, but only in notices delivered before December 31, 2010.

7 Even after the safe harbor for the sample clauses expires, the notices can continue to be used “so long as these notices comply with the privacy rule.” 8 That is an ambiguous statement, given that the regulatory staff makes negative comments about the sample clauses in its introduction to the fi nal rule—are the regulators saying that the sample clauses are compliant or not?

9

Scope of Safe Harbor.

Just how broad is the safe harbor?

The revised regulations say this:

(a) Model privacy form. Use of the model privacy form in Appendix A of this part, consistent with the instructions in Appendix A, constitutes compliance with the notice content requirements of §§ 313.6 and

313.7 of this part, although use of the model privacy form is not required.

In the introduction to the fi nal rule, the regulatory staff goes further (emphasis added):

The Agencies agree that the model form satisfi es the requirements for the content of the notice required by the GLB Act, including sections __.6 and __.7 of the privacy rule; FCRA section 603(d) as described in section

__.6 of the privacy rule; and section __.23 of the affi liate marketing rule.

The Agencies note that the safe harbor applies to use of the model form, but does not and cannot extend to the institution specifi c information that is inserted in the model form. Proper use of the model form to comply with the privacy rule requires that institutions accurately answer the questions about their information collection and sharing practices, as well as provide to consumers, as applicable, a reasonable means and opportunity to limit sharing and honor any opt-out requests submitted.

10

Accurate answers by fi nancial institutions will not be easy or even actually “accurate” because of the regulatory choices made. For example, if a fi nancial institution does not currently share a particular type of information, but reserves the right to do so in an indefi nite future, what is the correct answer to the form’s question “Does [name of fi nancial institution] share” X type of information? The accurate answer is “No” because there is no sharing of X going on or even anticipated

CCH G

UIDE TO

C

OMPUTER

L

AW

N

UMBER

338 at the time the question is answered. But the form is not nuanced enough to allow an institution accurately to note that it is not sharing X now but possibly might share it in the future. So the answer that must be supplied is “yes”: in either PDF or HTML format. Where consumers agree to electronic receipt of the notice, institutions can send the notice by email either by attaching the notice or providing a link to the notice.” 17

A few commenters opined that they may not currently share but want to reserve the right to share in the future. In such a case, the correct response in the middle column is “yes,” consistent with the privacy rule.

11

The reference to the privacy rule is a reference to the fact that institutions may disclose current or anticipated practices— but the question itself is not so worded. In short, completing the model form accurately will be much like taking a multiple choice test: the more you know, the worse you’ll do because the choices are not suffi ciently nuanced and regulatory guidance may be needed on the mandated answer. When there are too many variances in privacy practices to provide the blunt answers required by the form, such as because of variations among products, institutions will need to use a separate form for each product.

12

Shorthand Language.

In order to make the complex legal concepts simple, the model form uses shorthand terms like

“everyday business purposes” to describe what would otherwise be a long laundry list of reasons institutions typically share information. In response to commentator fears that using the form would result in a loss of rights, the staff introduction to the fi nal rule says that no loss of rights is intended and that the shorthand may not be lengthened.

Amendments.

18

GLBA institutions send revised privacy notices, a question was raised regarding whether institutions must note each change or simply provide a new version showing a new effective date. The answer selected is the

“new version with an effective date” alternative.

19

Standard.

The form is a standard form that may not be altered, except within express parameters. This may preclude use of the form when it does not fully accommodate the relevant legal options. For example, the form’s default structure calls for a full, not a partial, opt-out from affi liate marketing, so the form may not be used to provide partial opt-outs.

13 This means that institutions with privacy structures as complex as the law might not be able to use the form, even though

Congress mandated development of an optional form for provision of GLBA disclosures.

Format.

The form is a two-page standard paper form

(printable on the front and back of one page) that may only be completed and altered pursuant to express instructions.

Formatting—from color, orientation (portrait orientation only) and font size, to “leading” space between the lines of text—is prescribed. The regulators intend to issue an electronic version of the form for use on websites and also to provide a “form builder” to assist institutions in creating allowable versions.

Opting Out.

Because GLBA allows consumers to opt-out of certain information sharing. A question asked what information could be collected from the person seeking to opt-out in order to ensure the institution deals with the correct person, e.g

., could a full or redacted SSN be required?

In the staff introduction, the regulators “strongly encourage”

GLBA institutions:

[T]o use some other form of identifi er, such as a randomly generated “opt-out code” provided in the notice that consumers can use to exercise their opt-outs without jeopardizing the security of their most sensitive personal information. A random code—which some institutions currently use—both protects consumers’ most sensitive information and at the same time can be used to link both the customer and account(s) to which the opt-out should apply. Such an approach would further simplify the opt-out process for consumers.

If such an approach is not feasible, institutions could use a truncated account or policy number to protect sensitive information. Of course, any opt-out means provided—including any information requirements imposed on consumers—must be reasonable under the privacy rule and reasonable and simple under the affi liate marketing rule. Institutions should keep these requirements in mind when requesting information beyond the consumer’s name and address.

20

Provision.

The GLBA literally does not require that its privacy notices be provided to consumers in “writing” only, 14 but it does require provision such that “each consumer can reasonably be expected to receive actual notice in writing or, if the consumer agrees, electronically.

” 15 An institution may reasonably expect that a consumer who conducts transactions electronically will receive actual notice if, among other examples, institutions “clearly and conspicuously post the notice on the electronic site and require the consumer to acknowledge receipt of the notice as a necessary step to obtaining a particular fi nancial product or service.” 16 The model form does not change this rule and is not intended to require use of a particular electronic format: “The Agencies agree that institutions can provide the notice electronically

Helpful Information . No good deed goes unpunished and the model form is no exception—institutions that believe they can usefully add consumer information such as privacy tips or information about fraud prevention should not do so, at least on the form:

The Agencies considered these suggestions and decided not to permit the inclusion of additional information in the fi nal model form. While an institution may believe

CCH G

UIDE TO

C

OMPUTER

L

AW

N

UMBER

338 this information is useful or important, we believe that the addition of such information to the model form defeats the purpose of providing a clear and usable notice about information sharing practices and consumer rights. The

Agencies do not preclude an institution from providing such information in other, supplemental materials, if the institution wishes to do so .

21

This is an illustration of the confusion ultimately created by the model form. The point of the model was to decrease consumer confusion; yet for each defect in the form, the regulatory response is that an institution may send supplemental information. The result is that consumers still may get long, detailed disclosures and information that the regulators simultaneously criticize. It would have been more helpful and true to the Congressional mandate had the regulators faced the fundamental issue. What is the actual purpose of privacy disclosures and what must institutions actually do: (1) promote basic consumer understanding, or

(2) provide detailed supplemental information to deal with actual legal complexities?

The answer should be Number 1, but the regulators were unclear or lost courage and appear to have gone with Number

2. Accordingly and absent clarifi cation, the model form will only be truly useful to institutions whose information practices mirror its simplicity and default rules. an affi liate marketing notice that complies fully with the affi liate marketing rule requirements.

22

These kinds of examples illustrate why the model form may present more of an unsafe safe harbor for many institutions, and that is a disappointment. Both consumers and institutions deserve better. One solace for both may be this: when faced with the dilemma of whether supplemental (complex) information must be provided under, for example, unfair acts or deceptive practices principles, it may be helpful to remember that, at least at the federal level, (1) the very same federal regulators who crafted the form include regulators charged with enforcing those principles and some of the other laws the form appears to treat in a “this should be suffi cient” fashion, and (2) the form allows inclusion of text to address state law variations in a particular part of the form. In that setting, would the FTC for example, bring an action for unfair acts or deceptive practices for failure to supply supplemental information eschewed by the form it jointly created and issued? One would hope that the form is not that deceptive and that courts will conclude that if it looks like a safe harbor and smells like a safe harbor, it is a safe harbor, notwithstanding regulatory-created confusion.

Congress mandated more than that; it mandated development of an optional form “for the provision of disclosures under this section,” i.e

., all of them and not just some of them for some institutions. At the same time, Congress mandated that the form be “comprehensible to consumers” and “enable consumers easily to identify the sharing practices of a fi nancial institution” and be “succinct.” Any fi nancial institution or other business bound to comply with current data protection laws could have told Congress (and likely did) that such was impossible. The model form proves it cannot be done and the regulators admit it:

Some institutions objected to the description of the optional affi liate marketing provision enacted under the FACT Act …. These commenters are correct that this provision, unlike the others, is about the use of shared information for marketing. and Kleimann worked to ensure accuracy in the model form, it was evident at the outset that this particular provision would be very diffi cult to explain in a simple and clear way to consumers and be precisely true to the statutory language .

While the Agencies

The fi nal formulation we proposed tested suffi ciently well to show that consumers understand its basic meaning. it in their GLB Act privacy notice, must separately send

Including the affi liate marketing notice and opt-out in the model form is optional. Institutions that are required to provide this notice, and elect not to include

Endnotes

1 15 USC 6801–6827 (1999). See also Financial Services

Regulatory Relief Act of 2006, Pub. L. 109-351 (amending

GLBA to require federal banking agencies to create an optional, model disclosure form).

2 See , e.g

., discussion of FTC enforcement actions in ¶ 12.16[4]

[d] of The Law of Electronic Commercial Transactions (2003-09,

A.S. Pratt & Sons).

3 See § 728 of The Financial Services Regulatory Relief Act of

2006, Pub. L. 109-351 (2006), adding 15 USC 6803(e).

4 fi nal model privacy form was developed jointly by the

OCC, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System

(Board), FDIC, OTS, NCUA, FTC, Commodity Futures

Trading Commission (CFTC), and SEC. Versions are largely but not always identical.

5 A copy of the rule, including the form and the joint explanation by the regulatory staff, is at http://www.ftc.

gov/privacy/privacyinitiatives/PrivacyModelForm_Rule.

pdf (“Final Rule”). Citations in this article are to the aforesaid copy; the Federal Register citation is 74 Federal Register

62890(12/1/09).

6 “This rule is effective on December 31, 2009, except for the following amendments, which are effective January 1, 2012:

Instructions 3B, 10B, 17B, 24B, 31B, 38B, 45B, and 52B removing paragraphs (g) to 12 CFR 40.6, 216.6, 332.6, 573.6, and 716.6,

16 CFR 313.6, and 17 CFR 160.6 and 248.6, respectively; and

Instructions 7B, 14B, 21B, 28B, 35B, 42B, 49B, and 55B removing

Appendixes B to 12 CFR parts 40, 216, 332, 573, and 716, 16

CFR part 313, and 17 CFR parts 160 and 248, respectively.”

7 Final Rule at 51(staff introduction) (“Financial institutions will not be able to rely on the safe harbor by using the Sample

CCH G

UIDE TO

C

OMPUTER

L

AW

N

UMBER

338

Clauses in notices delivered or posted on or after January

1, 2011. Privacy notices using the Sample Clauses that are delivered to consumers … during the transition period, will have a safe harbor for one year after delivery or posting”).

8 Id . at 51.

9 See id ., Part IV beginning at 48.

10 Final Rule at 46 (staff introduction, emphasis added). The blanks in the citations allow each agency to fi ll in their own version of the referenced regulations. For example, for the

GLBA privacy rule, FTC the blanks would be completed with

“16 CFR § 313.”

11 Id . at 33.

12 Id . at 33 (staff introduction) “[S]ome commenters expressed concern that their information sharing practices were suffi ciently complex that they could not answer “yes” or

“no,” stating that they had different practices for different products. Institutions that elect to use the model form must answer the questions in the fi nal model form as directed in the proposal. If an institution elects to use the model form, it must either harmonize its practices so one notice applies to all its products, or it must provide separate notices for products subject to different information sharing practices.”

13 See id . at 39 (staff introduction) and form instruction in

Appendix A at C(2)(d)(6).

14 See Chapter 11.06[2] of The Law of Electronic Commercial

Transactions (2003-09, A.S. Pratt & Sons) for E-Sign consumer disclosure rule where written information is required to be provided to a consumer.

15 16 CFR 313.9(a) (FTC version).

16 Id . at (b)(1)(iii).

17 Final Rule at 47 (staff introduction).

18 See id . at 34 (staff introduction), “Because the laws governing disclosure of consumers’ personal information are not easily translated into short, comprehensible phrases, the table uses more easily understandable short-hand terms to describe sharing practices. We do not believe that these short-hand terms diminish the laws’ provisions, as some commenters asserted. If, as these commenters suggest, the Agencies add to the laundry list of descriptive terms to make the provisions in the table more ’precise,’ we believe it will defeat the purpose of making this information more understandable to consumers. Thus, the Agencies have chosen not to provide detailed descriptions for each of the reasons in the table; we re-affi rm that institutions’ ability to share information in accordance with the statutory provisions would not be limited or otherwise modifi ed by using the model form language.

. . . . In all these instances, the lack of explicit references in the model form to certain of the exceptions does not mean that an institution cannot take advantage of all the exceptions provided for in the law.”

19 Final Rule at 45 (staff introduction, footnotes omitted): “One advocacy group supported adding an extra column to the notice table highlighting specifi c changes made since the previous notice.

After considering these comments, the Agencies determined that the simplest way to help consumers identify how recently the notice was changed is to include a “revised

[month/year]” notation in the upper right-hand corner of page one of the notice. The revised date, in minimum

8-point font, is the date the policy was last revised. Of course, institutions can signal material changes in their policies by, for example, use of a cover letter that describes any changes.”

20 Id . at 38-39 (citations omitted).

21 Id . at 47-48 (emphasis added).

22 Final Rule at 36 (staff introduction, footnotes omitted, emphasis added).