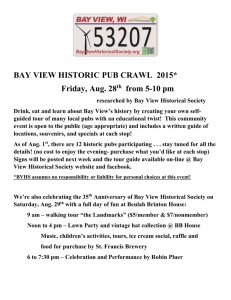

A P C

advertisement