Understanding contribution of content to public document repositories Mani Subramani (

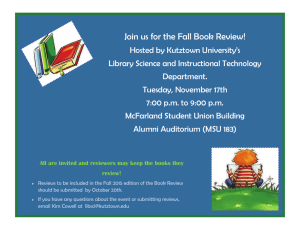

advertisement