International Journal of Accounting Information Systems 13 (2012) 21–40

Contents lists available at ScienceDirect

International Journal of Accounting

Information Systems

Role of IT executives in the firm's ability to achieve

competitive advantage through IT capability

Jee-Hae Lim, Theophanis C. Stratopoulos ⁎, Tony S. Wirjanto

University of Waterloo, Waterloo, Ontario, Canada N2L 3G1

a r t i c l e

i n f o

Article history:

Received 5 April 2011

Received in revised form 28 June 2011

Accepted 1 July 2011

Keywords:

Business value of IT

CIO

IT capability

Structural power

Tobin's q

a b s t r a c t

Contrary to prior studies that have tried to examine the role of IT

capabilities (ITC) on firm performance in isolation from the role of senior

IT executives, we propose that the two are linked. More specifically we

argue that there is a positive relationship between the structural power

of senior IT executives and the likelihood that the firm will develop

superior ITC. Furthermore, the contribution of ITC to a firm's competitive

advantage is much stronger in firms with powerful senior IT executives

as they are the driving force that may ensure the continuous renewal of

ITC. We develop a two-stage econometric model designed to test this

chain hypothesis that the structural power of senior IT executives will

affect a firm's ability to achieve superior ITC, in turn driving firm

performance. Empirical evidence based on a sample of large US firms

strongly supports both of our hypotheses.

© 2011 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

1. Introduction

Anecdotal evidence based on companies that have been known for their superior organizational IT capability

indicates that powerful senior IT executives1 play a pivotal role in orchestrating their company's success. The

objective of this study is twofold. A two-stage approach is used in order to examine the contribution of senior IT

executives on their firm's ability to achieve superior IT capability, and the impact of co-presence of powerful

senior IT executives in firms with superior IT capability on their firm's competitive position.2

⁎ Corresponding author.

E-mail addresses: jh2lim@uwaterloo.ca (J.-H. Lim), tstratop@uwaterloo.ca (T.C. Stratopoulos), twirjant@uwaterloo.ca

(T.S. Wirjanto).

1

Salient examples include Shack at PNC, Kepler at Dow Chemical, Webb at Equifax, Stanley at Harrah's, and Mott at Wal-Mart.

2

Our study concurs with prior research that firms use many different titles for their senior IT executives (e.g., CIO, CTO, VP,

Director, Managing Director). We are speculating that for brevity the majority of studies tend to use the blanket label ‘CIO’ to refer to a

firm's senior IT executive. While this is convenient, it is an oversimplification. It ignores the fact that a senior executive's title and

number of titles is a proxy of their power within the organization, i.e., a proxy for their structural power (Finkelstein, 1992).

1467-0895/$ – see front matter © 2011 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

doi:10.1016/j.accinf.2011.07.001

22

J.-H. Lim et al. / International Journal of Accounting Information Systems 13 (2012) 21–40

Our study builds on and integrates two streams of research that fall under the broader IT business

value literature: (1) Studies that examine role of organizational IT capability on firm performance. One of

the first studies in this area by Bharadwaj (2000) has shown strong support for the hypothesis that firms

with superior IT capability perform better than their competitors. However, a follow up study by

Santhanam and Hartono (2003) found that the role of IT capability on firm performance is weaker once

you account for the firm's prior performance. In general the results from IT capability studies remain

mixed. (2) Studies that examine the role of senior IT executives on their firm's market and financial

performance. According to Chatterjee et al. (2001), markets react positively to the announcement of

the creation of a new CIO position. Khallaf and Skantz (2011) find that CIO appointments improve

firm financial performance but the performance improvement is largely limited to ‘firms appointing a CIO

for the first time’ and first movers. Notwithstanding the contribution of both of these studies (Chatterjee

et al., 2001; Khallaf and Skantz, 2011), a question with significant practical implications for senior

business executives and senior IT executives remains unanswered. Do incumbent senior IT executives

add value? The importance of evaluating the value adding contribution of incumbent senior IT executives

has been suggested by Chatterjee et al. (2001; p. 58): “…evidence suggests that CIOs experience a high

turnover rate, relative to other senior executives. Is this solely a function of poor performance by

incumbents?”

In this study we propose integrating these two streams of research in order to better understand the

value adding contribution of senior IT executives and the role of IT capability on their firm's performance.

Prior studies have either tried to examine the role of IT capabilities on firm performance (e.g., Bharadwaj,

2000; Santhanam and Hartono, 2003) or the role of senior IT executives on firm performance (Khallaf and

Skantz, 2011) in isolation. We propose that one should consider the role of senior IT executives in a

firm's ability to develop superior IT capability, and then the value added by senior IT executives

through superior IT capabilities. Building on existing literature (e.g., Raghunathan and Raghunathan,

1989; Grover et al., 1993; Armstrong and Sambamurthy, 1999) this study argues that there is a positive

relationship between the structural power of senior IT executives and the likelihood that the

firm will develop superior IT capability. Structural power is ‘perhaps the most commonly cited type

of power; it is based on formal organizational structure and hierarchical authority' (Finkelstein, 1992;

508). Furthermore, given the dynamic nature of IT capabilities (Bhatt and Grover, 2005; Lim et al.,

forthcoming) the contribution of IT capability to a firm's competitive advantage is much stronger in firms

with powerful senior IT executives as they are the driving force that may ensure the continuous renewal

of IT capability.

The data set for testing our hypotheses was developed by integrating data from InformationWeek 500

(proxy for firms with superior IT capability), Lexis-Nexis and a variety of online sources (search for official

title and number of titles to proxy for structural power of senior IT executives) and Compustat (firm

performance data) for the period 1997–2004. A two-stage econometric model is used to test the chain

hypothesis that the power of senior IT executives will affect a firm's ability to achieve superior IT capability,

and that this in turn drives firm performance. Empirical evidence based on a sample of large US firms

strongly supports our hypotheses.

This study contributes to prior literature on IT capability and firm performance by demonstrating

that the impact of superior IT capability on a firm's competitive performance is contingent upon the

structural power of the firm's senior IT executive. The results show that in firms where senior IT

executives have high power, the effect of superior IT capability on firm performance remains strong,

even when accounting for the firm's prior performance, time, and industry effect. Furthermore, our

study contributes to the growing literature on the role of senior IT executives (Chatterjee et al., 2001;

Dehning and Stratopoulos, 2003; Khallaf and Skantz, 2011; Masli et al., 2011) by illustrating that the

impact of a firm's senior IT executive on its performance is channelled through superior IT capability.

Identifying antecedents of IT capability, i.e., factors that lead a firm to achieve and sustain superior IT

capability, as well as recognizing the role that these factors play on the rent yielding capacity of IT

capability, helps to illuminate the proverbial black box of IT business value research. Finally, this study

has important practical implications for senior business executives who want to compete through IT

enabled strategies. The message is that bestowing more power on senior IT executives increases the

likelihood that the firm will develop and sustain superior IT capability, the sine qua non for an IT

enabled strategy.

J.-H. Lim et al. / International Journal of Accounting Information Systems 13 (2012) 21–40

23

2. Theoretical foundation and hypotheses development

2.1. IT capability and firm performance

Studies exploring the effect of organizational IT capabilities on firm performance figure prominently in the

body of IT business value literature. The pioneering empirical study by Bharadwaj (2000) defines organizational

IT capability as a firm's ability to mobilize and deploy IT based resources (i.e., flexible IT infrastructure, human

IT resources, and intangible IT enabled resources such as knowledge, synergy, and customer orientation) in

combination with other resources and capabilities.3 Bharadwaj (2000) and all subsequent studies employed

what Newbert (2007, p. 127) calls a ‘resource heterogeneity approach.’ That is, they argue on theoretical

grounds that IT capability is valuable, rare, inimitable, and/or non-substitutable. They use InformationWeek 500

(IW500), Computerworld's Premier 100 (CW100), or CIO Magazine IT excellence awards (CIO100 Award) to proxy

the ‘amount’ of IT capability possessed by a firm (i.e., these firms posses superior IT capability), and correlate

this IT capability superiority to some measure of competitive advantage or performance.

Using ‘IT leaders’ drawn from the annual special issue of InformationWeek 500 (IW500) over the period

1991–94 to identify firms with superior IT capability, Bharadwaj (2000) finds that these firms perform better

than their matched competitors based on profit- and cost-based performance measures. Using the same data

set but with industry performance as the benchmark, a subsequent study by Santhanam and Hartono (2003)

finds that firms with superior IT capability perform above the industry average, but the results are weaker once

they account for the firm's prior financial performance. Identifying firms with superior IT capability based on

the 1993 Computerworld's Premier 100 list, Dehning and Stratopoulos (2002) use DuPont analysis to show that

firms with superior IT capability achieve profitability as well as efficiency payoffs while high-performing nonIT capable firms have profitability but no-efficiency advantage.

More recent studies have explored and contrasted the effect of superior IT capability on firm performance

pre Y2K (eighties and nineties) versus post Y2K with mixed results. Wang and Alam (2007) use Information

Week 500 ranking, for the years 1991, 1992, and 1995–2002, as a proxy for superior IT capability and they find

that IT capability is value-relevant and provides incremental explanatory power for firm valuation beyond

traditional accounting information. Muhanna and Stoel (2010) use the top 40 to 60 firms from the annual

Information Week 500 ranking to evaluate and contrast the effect of superior IT capability on stock market

valuation, and they find strong results in the pre- (1992–1994) and post-Internet commercialization era

(1999–2006). However, the results of the Masli et al. (2011) study contradict these findings. Using CIO

Magazine IT excellence awards (CIO 100 Award) over the 1988–2007 period, Masli et al. (2011) find that while

firms with superior IT capability performed above the industry benchmark before 2000, this performance

advantage disappeared in the post-1999 period. The authors argue that this is due to a structural shift

associated with the dot com crash. Furthermore they observe that only firms achieving IT capability

superiority in multiple years outperform the industry benchmark before as well as after the dot com crash.

In general the findings of prior studies seem to reflect the perceptions and frustrations of senior

business executives with IT. While executives agree on the value adding contribution potential of IT

resources and capabilities, they also realize that there are significant barriers that prevent firms from

exploiting the full benefit of IT investments (Masli et al., 2011). Hence, an exploration of the antecedents

that lead to the continuous development of IT capability and their reinforcing effect on firm performance

would be the next logical step for studies on the effect of organizational IT capabilities on firm performance.

The reification of ‘firm’ in the definition of IT capability (a firm's ability mobilize and deploy IT based

resources in combination with other resources and capabilities) renders the firm as a purposeful entity and

detaches IT capability development from the people involved. However, according to the upper echelon theory,

organizational outcomes are predicted by managerial characteristics (Hambrick and Mason, 1984). Therefore it

seems reasonable to consider the role of senior IT executives as an antecedent in the firm's ability to develop

superior IT capability, as well as a factor that could enhance a firm's ability to exploit its superior IT capability.

3

Numerous other studies have argued or demonstrated the benefits of integration of IT with improvements in organizational

structure and business processes (complementary resources). A representative sample of these studies includes: Bhatt and Grover

(2005), Brynjolfsson and Hitt (1998, 2000, 2003), Milgrom and Roberts (1990), Powell and Dent-Micallef (1997), Ravichandran and

Lertwongsatien (2005), and Zhu, 2004. In a similar fashion Armstrong and Sambamurthy (1999) refer to the effective rutinization/

infusion of IT on the firm's value chain and business strategy as IT assimilation.

24

J.-H. Lim et al. / International Journal of Accounting Information Systems 13 (2012) 21–40

2.2. Senior IT executives and firm performance

As top management teams recognized the strategic potential of IT during the mid-1980s, the

management of IS functions naturally evolved. Data processing managers were gradually replaced with IT

executives and focus shifted from delivery of basic IT services to the exploitation of IT for competitive

advantage (Galliers and Leidner, 2003). In order to achieve more effective management of IT resources and

capabilities, during the late eighties and nineties an increasing number of firms elevated the structural

power of their senior IT executives by announcing the creation of a new position: Chief Information Officer

(Chatterjee et al., 2001). This trend is consistent with the view that assets of higher importance will be

entrusted to managers of higher rank (Raghunathan and Raghunathan, 1989).

Given that higher ranking IT executives have more power to affect organizational actions (Raghunathan

and Raghunathan, 1989), the explicit presence of more powerful senior IT executives in a firm highlights the

role and importance of IT capability to enhance strategic advantage (Applegate and Elam, 1992; Armstrong

and Sambamurthy, 1999). For example, such managers are more likely to concentrate on the following issues:

the creation of shared knowledge between business and IT managers (Chatterjee et al., 2001), the alignment

between business and IT objectives (Sambamurthy and Zmud, 1994; Bassellier et al., 2003), and the creation of

a positive shared view towards IT across the upper echelon of the organization (Chen et al., 2010).

Arguing that the creation of a new CIO position reflected changes in top management thinking and policy

regarding the role of IT and firms' approaches to IT governance, Chatterjee et al. (2001) use event study

methodology to find shareholders' reaction to these announcements. Analyzing a sample of 96

announcements of newly created CIO positions, from the period 198 to 1998, they find that markets react

positively to a firm's decision to assign higher rank to its senior IT executive. A follow up study by Khallaf and

Skantz (2007) contrasted market reaction to new versus existing CIO positions. Based on evidence regarding

461 CIO appointments during the period 1987–2002, they conclude that there is no significant difference in

the market's reaction to the two types of announcements. A more recent study by the same authors (Khallaf

and Skantz, 2011) looked at the change in long-term accounting performance relative to the corresponding

industry benchmark in the years following the appointment of a new senior IT executive. Analyzing 359

announcements from 1987 to 2002 they report that CIO appointments improve firm financial performance

but the performance improvement is largely limited to ‘firms appointing a CIO for the first time’ and first

movers.

Another study by Dehning and Stratopoulos (2003) approaches the issue of the value adding contribution

of senior IT executives from a different angle. Instead of looking at market reaction or change in financial

performance, Dehning and Stratopoulos (2003) evaluate factors that can contribute to a company's duration

of competitive advantage. They use ‘management rating,’ one of the criteria used to select the companies in the

1993 Computerworld's Premier 100 list to proxy the ‘amount’ of superior managerial IT skills possessed by a

firm, and find a positive association with the firm's ability to sustain its competitive advantage.

In general these studies have drawn on the Resource Based View (RBV) to provide the theoretical

justification for the value adding contribution of senior IT executives on the firms' stock market valuation,

financial performance, or duration of competitive advantage. They have used RBV to argue that a senior IT

executive is an asset or strategic resource that delivers value through IT resources and capabilities. Mata et al.

(1995) explained that ‘managerial IT skills’ are a likely source of competitive advantage because they are

valuable and heterogeneously distributed across competing firms. According to Dehning and Stratopoulos

(2003) superior managerial IT skills are believed to be a source of sustainable competitive advantage because

they enable companies to manage the technical and market risks of IT investment, they are developed over

time through the accumulation of experience, they are tacit and causally ambiguous, and they are the result of

socially complex processes.

Two gaps were illuminated through a review of literature on the role of senior IT executives on firm

performances. First, with the exception of Dehning and Stratopoulos (2003), the main emphasis has been on

new appointments of senior IT executives. As Chatterjee et al. (2001) have pointed out, relatively little is

known about the value adding contribution of incumbent senior IT executives. Second, the path through

which senior IT executives add value to their firms has been treated as a black box. Empirical studies that we

have reviewed on the role of IT executives on firm performance either ignore the role that senior IT

executives have played in developing a firm's IT capability or they treat their firm's IT capability as a control

variable.

J.-H. Lim et al. / International Journal of Accounting Information Systems 13 (2012) 21–40

25

2.3. Senior IT executives and IT capability

As data processing managers were gradually replaced with IT executives and their focus shifted from

day-to-day operations and IT spending to IT strategic approaches, the scope and responsibilities of senior IT

executives expanded, leading to promotion and increased power (Chatterjee et al., 2001; Galliers and

Leidner, 2003). This combination of power and expanded roles suggests a greater influence on the

leadership team (Mintzberg, 1983). Several studies looked at the role and relationships of IT executives

within the firm and their efforts to infuse IT on the firm's value chain and business strategy (e.g.,

Raghunathan and Raghunathan, 1989; Grover et al., 1993; Armstrong and Sambamurthy, 1999).

Analyzing managerial roles of IT managers, Grover et al. (1993) argue that the hierarchical level of

management influences the roles of senior IT executives. In general, higher-level senior IT executives tend to

focus more on such roles as: (1) ‘liaison’ between the organization and suppliers or customer; (2) ‘monitor’ of

the external environment for technical changes, competition and identification of new ideas from sources

outside of the organization; and (3) ‘entrepreneur’ who identifies business needs and develops solutions that

change business situations. As an entrepreneur the senior IT executive ensures that rapidly evolving technical

opportunities are understood, planned, implemented, and strategically exploited in the organization. Through

entrepreneurship they play a greater role in influencing overall strategy and planning in the organization and

they translate these organizational strategies and plans into definite IS actions (Grover et al., 1993).

Raghunathan and Raghunathan (1989) explore whether the organizational rank of the senior IT executive

influences the way in which IS tasks are undertaken in organizations. They conclude that rank has significant

linkages to the organizational role of IS and to the emphasis placed on various dimensions of IS planning.

Building on organizational theory Raghunathan and Raghunathan (1989) argue that hierarchical organization

structure confers formal authority and constitutes a base of power to affect and influence organizational

actions. To this point Karimi et al. (1996) have shown that senior IT executives holding the title CIO actively

spend more time interacting with stakeholders outside the firm and on more general corporate strategic

planning. Building on prior literature that has proposed, among other things, that with lower rank of

responsible IT executives the likelihood of a successful IT effort declines, Raghunathan and Raghunathan

(1989) conclude that the rank of senior IT executives in the organizational hierarchy could be an important

factor affecting the success of IS and its use as a strategic, competitive weapon.

In addition to this, research has shown that participating in the firm's top management team and interacting

with senior business executives enhances the business knowledge of senior IT executives. This chain-effect is very

important as it affects a firm's ability to successfully integrate IT with improvements in organizational structure

and business processes (firm's value chain) and business strategies (Armstrong and Sambamurthy, 1999).

Raising the profile and rank of senior IT executives in the executive team provides economic justification to the

executive team for IT projects. This in turn supports the argument for increased attention and allocation of

resources for strategic IT projects. In contrast, if the senior IT executive is not part of the executive team, IT

prioritization is less likely to have the executive team's support and commitment (Applegate and Elam, 1992;

Armstrong and Sambamurthy, 1999). In summary this stream of research provides the theoretical foundation for

the following position: The structural power of senior IT executives (i.e., their power within the firm due to their

formal position) is an antecedent to their firm's ability to develop superior organizational IT capability.

2.4. Synthesis

Examining these three streams of research sequentially and in isolation from each other serves two purposes.

First, it reveals potential gaps in each stream. Second, it clarifies the ease with which these gaps can be addressed

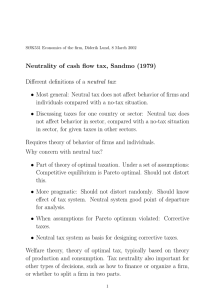

by integrating these three streams. Fig. 1 summarizes the main points of our review and the proposed synthesis.

More specifically, Fig. 1 — Panel A shows that ‘antecedents of IT Capability’ are missing from the stream of

research ‘IT Capability and firm performance.’ Panel B shows that the impact of IT executives on firm performance

is going through a ‘black box.’ Panel C shows that both of the above gaps can be filled by incorporating the stream

of research on the senior IT executives and IT capabilities. The resulting synthesis is shown in Panel D.

The proposed synthesis of these three streams of research is well supported by anecdotal evidence. For

example, Intel senior IT executives played a critical role in the firm's ability to align IT with business goals,

eventually developing superior IT capability. In the late-nineties, Intel's IT organization was known for its

inefficiency (high cost) and ineffectiveness (failing IT projects). In an attempt to change this, D. Busch was named

26

J.-H. Lim et al. / International Journal of Accounting Information Systems 13 (2012) 21–40

A: IT Capability and firm performance

B: IT executives and firm performance

C: Senior IT executives and IT Capabilities

D: Synthesis

Fig. 1. Theoretical foundation and synthesis.

VP of IT in 1999. He created a vision for the IT organization to become a value-adding contributor to Intel's internal

and external success, and a mission to enhance the company's success with outstanding strategic leadership and

IT services (Westerman and Curley, 2008). He planned to achieve this by managing IT like a business. Busch set a

goal to create $100 million in net business value by 2002, without incurring any additional costs. In his role, Busch

not only achieved this goal, but the IT organization he redesigned won the coveted Intel Quality Award (Curley,

2006). In 2002, D. Busch was appointed as the first VP and co-CIO in the company's history, with a mandate to

help the company in its efforts to become a total e-corporation (Rosencrance, 2002).

Clearly, the case of Intel as well as the cases of several other firms known for their superior

organizational IT capability indicates the pivotal role of powerful senior IT executives in orchestrating their

company's success. This study argues that senior IT executives contribute to their firm's competitive

position through the development of such superior IT capability. Thus we postulate that:

H1. The structural power of senior IT executives will be positively associated with the development of

superior organizational IT capability.

H2. Impact of senior IT executives on firm's competitive position is channelled through superior IT capability.

3. Research methodology

3.1. Sample selection

The data set for testing these hypotheses was developed by integrating data from several sources.

Consistent with prior studies (Bharadwaj, 2000; Santhanam and Hartono, 2003; Wang and Alam, 2007;

Muhanna and Stoel, 2010; Stratopoulos and Lim, 2010; Lim et al., forthcoming) a firm's appearance in the

annual special issue of the InformationWeek 500 is considered a proxy for IT capability superiority. We use

Lexis-Nexis and a variety of online sources in order to search for official title and number of titles to proxy for

structural power of senior IT executives. Finally, we use Compustat for financial data. To account for the

proposed structural shift associated with the dot com crash (Masli et al., 2011), hypotheses were tested based

on data from the period 1997 to 2004.

J.-H. Lim et al. / International Journal of Accounting Information Systems 13 (2012) 21–40

27

Given that for RBV, the de facto theoretical foundation of this study, understanding how a firm

compares to its competitor is critical; and in order to make the results more interesting to professionals,

Hoover's Handbook of American Business was used to identify and annually match each IT capable firm with

its top three competitors. Hoover's compiles the profiles of major US firms each year (i.e., firms with sales

of $2 billion or more). Each profile includes a list of the firm's competitors, and this list is updated each year.

On average there are approximately 20 competitors listed for each firm. Hoover's was chosen for the

matching process for two reasons. First, Hoover's was involved in the preparation of the IW500 report as a

provider of financial data (Weston, 1998). Therefore it is likely that the sample of firms used by IW overlaps

with the population of firms tracked by Hoover's. Second, Hoover's is a source of firm-specific information

geared towards the professional community, and hence is more likely to reflect a practitioner-oriented list

of close competitors of IW500 firms. The final sample for firms with superior IT capability and their

competitors (non-IT capable firms) contains 960 publicly traded companies. The data set covers the same

spectrum of industries and maintains a similar composition (622 IT leader firms and 338 non-IT leader

firms) as in prior studies (Stratopoulos and Lim, 2010; Chen et al., forthcoming; Lim et al., forthcoming).

3.2. Measurement of senior IT executives' structural power

Titles that are stated in annual reports clearly relate to authority and responsibility. In fact, a higher

number of official titles brings greater power and expanded responsibility (Finkelstein, 1992), as well as

more practical benefits such as higher compensation (Marlin, 2004). 4 Accordingly, the official title and the

number of secondary titles of senior IT executives indicate a wider spectrum of expertise, greater influence

outside the IT organization, as well as more structural power. For each IT capable and non-IT capable firm in

the sample, we searched proxy statements, such as Form 10-Ks and DEF-14A from the U.S. Securities and

Exchange Commission (SEC), to identify each senior IT executive's name, official title, and number of titles.

Due to a lack of publicly-available data regarding senior IT executives, the combination of data sources was

expanded to include proxy statements, Lexis-Nexis, and several online sources. In order to verify and

enhance the completeness and accuracy of our data, a subsequent manual review of each senior IT

manger's bio data was conducted via Lexis-Nexis as well as seven online search engines (LinkedIn, Company

Biographies, Factiva, Forbes People Tracker, Marketwatch.com, Zoominfo People, and BusinessWeek People).

This search produced 317 different official titles for senior IT executives. 5 Consistent with the extant

literature (Finkelstein, 1992), we use the official title as well as the number of titles as a proxy for the

structural power of senior IT executives. In other words we assume that a senior IT executive with the

formal title of CIO or CIO with additional official titles (e.g., CIO and Executive Vice President) possesses

greater power than senior IT executives without the CIO title (e.g., Managing director). In the remainder of

this study the group of high power senior IT executives are referred to as CIO and the rest as Non-CIO.

3.3. Market performance measure: Tobin's q

Firm performance in this study is measured by Tobin's q. Tobin's q is defined as the market value of the firm

divided by the replacement cost of its assets. As a performance measure it is forward-looking, risk-adjusted, and

less vulnerable to changes in accounting practices. It has also been used as a proxy for the firm's intangible value.

More specifically, q values that are greater than one have been interpreted as an indicator of an unmeasured

source of value attributed to the firm's intangible value (Bharadwaj et al., 1999). Given that typical IT benefits are

related to such intangibles as improved customer satisfaction, and improved service quality and agility, Tobin's q

has been used as a performance proxy for examining how firm performance relates to IT investment (Bharadwaj

et al., 1999; Chari et al., 2008; Ravichandran et al., 2009), IT synergies (Tanriverdi, 2006), and superior IT

capability (Masli et al., 2011). Overall, Tobin's q is the kind of performance measure more likely to capture and

4

The result of a survey by the IT research firm Alinean shows that senior IT managers with multiple titles are among the highest

paid IT managers and receive compensation packages of $1 million or more (Marlin, 2004).

5

A sample of these titles included Chief Information Officer (CIO), Chief Technology Officer (CTO), Sr. V.P. of Information Systems

(IS)/Information Technology (IT)/Computing Information Systems (CIS)/Management Information Systems (MIS); V.P. of IS/IT/CIS/

MIS; Dir. of IS/IT/CIS/MIS; Exec. Dir. of IS/IT/CIS/MIS; Managing Director of IS/IT/CIS/MIS; Pres. Dir. of IS/IT/CIS/MIS.

28

J.-H. Lim et al. / International Journal of Accounting Information Systems 13 (2012) 21–40

reflect co-presence of such intangibles as good management skills (Adams et al., 2010) and superior IT capability

(Masli et al., 2011).

Consistent with the previous AIS literature, Tobin's q is computed as a ratio of market value [(fiscal yearend market value of equity)+ (liquidating value of the firms' outstanding preferred stock) + (current

liabilities)− (current assets) + (book value of inventories)+ (long-term debt)] to book value of total assets

(Chung and Pruitt, 1994).

3.4. Control variables

Two sets of control variables were selected to evaluate the role of IT executives on firm performance.

These control variables were based on a review of prior studies on IT investment and firm performance.

The first set controls for the effects of known factors that might be associated with IT capability, such as

size, prior performance, and reputation. Firm size (Lev, 1983; Cheng, 2005), natural log of total assets

(SIZE), represents a firm's ability to sustain a competitive advantage from its market power or positional

advantages, as well as superior financial and human resources endowments (Brynjolfsson and Hitt, 1996;

Roberts and Dowling, 2002; Morrow et al., 2007). The need to control for the past financial performance of

a firm (ROA) is twofold: (1) a firm's strategic IT capability choice could be a function of its past performance (Santhanam and Hartono, 2003), and (2) it is likely that the selection of firms with superior IT

capability by industry experts might be influenced by the firm's past performance (Bharadwaj, 2000). A

firm's reputation might be another factor that may influence the selection of firms with superior IT

capability by industry experts. Market-to-book-value (MV) has been suggested as a proxy for reputation

because it captures tangible and intangible assets (Roberts and Dowling, 2002), as well as the market's

expectations of future economic returns (Mueller, 1990).

The second set controls for the effects of known factors that might be associated with firm performance,

such as R&D, advertising and capital expenditures. R&D intensity is viewed as a proxy for a firm's intangible

capital, which may enhance technology pursuit and firm performance (Scott and Pascoe, 1987; Miller, 2006).

Advertising (AD) and capital expenditure (CAP) are incorporated as well, as they were identified by Hitt and

Brynjolfsson (1996) and Masli et al. (2011) as having a significant impact on firm value. Finally, we control for

the fixed industry and year effects. See Appendix A for a list of variables and their description.

3.5. Econometric model

This study argues that IT capable firms perform better than their competitors and executives with more

power are more likely to contribute to the firm's ability to achieve superior IT capability. Ideally this

argument would be tested by contrasting the performance of the same firm given two different scenarios.

In the first scenario a powerful IT executive in a firm helps develop superior IT capability, whereas in the

second scenario the IT function of the same firm has been managed by a less powerful IT executive and the

firm had chosen not to develop the IT capability. Since we cannot make this type of comparison with

archival data, the second best approach is to contrast performance of firms with superior IT capability

versus the performance of firms with no IT capability. However, this approach is likely to lead to biased

estimates of the effect of strategic choice (IT capability versus non IT capability) on firm performance

unless we allow for endogeneity of strategic choices.

The underlying assumption behind a firm's strategic choices (e.g., whether or not to empower IT executives,

develop superior IT capability) is that such choices are not random, but compatible with firm attributes and

industry conditions. That is strategic choices are endogenous and self-selected (Hamilton and Nickerson, 2003;

Shaver, 1998). Ignoring the self-selection issue is equivalent to assuming that firm performance is independent of

the firm's choice regarding IT executives and IT capability. But such an assumption is unrealistic and would

introduce bias in the estimated coefficients. Furthermore, there is no way of predicting ex ante the direction and

size of bias (Hamilton and Nickerson 2003). In other words, we don't know whether firms that chose to assign

higher power to their senior IT executives in the hope that this will lead to superior IT capability and better

performance could have performed better or worse had they chosen not to make these strategic choices. Failure

to control for endogeneity may therefore lead to faulty conclusions about theoretical propositions.

This study attempts to alleviate endogeneity bias by employing a two-stage estimation with correlated

error terms. Formally, we specify a system of two equations (Eq. (1) and (2)) for testing the following chain

J.-H. Lim et al. / International Journal of Accounting Information Systems 13 (2012) 21–40

29

hypothesis: IT executives affect a firm's ability to achieve superior IT capability (Eq. (1)), and this in turn

drives their firm's performance (Eq. (2)).

yit = 1

ρyit−1 + δ1 CIOit−1 + δ2 SIZEit−1 + δ3 ROAit−1 + δ4 MVit−1 +

+ ηi + ϕt + uit > 0

qit = μqit−1 + β1 R&Dit + β2 ADit + β3 CAPit + γŷit + αi + ψt + εit

ð1Þ

ð2Þ

where t = 1,..,T, i = 1,…,N, and

1 for firms with superior IT capability, 0 otherwise

1 for Senior IT executive with the formal title of CIO or CIO with additional official titles,

0 otherwise

SIZEit − 1 natural log of total assets

ROAit − 1 return on assets

MVit − 1 market-to-book value

Tobin's q,

qit

research and development

R & Dit

advertising expenditures

ADit

capital expenditures

CAPit

ŷit

predicted value from the first-stage regression

ηi and αi fixed effects in Eqs. (1) and (2) respectively

ϕt and ψt time effects in Eqs. (1) and (2) respectively

uit and εit other time-variant unobserved variables assumed to be uncorrelated with vector of observable

firm characteristics in Eqs. (1) and (2) respectively.

yit

CIOit − 1

1[.] in Eq. (1) is an indicator function based on Lim et al. (forthcoming) and models firm i's ability to

achieve superior IT capability (yit). The expression in square brackets represents the ability of firm i to

achieve superior IT capability. If the ability is sufficiently high, firm i has superior IT capability, in which

case yit takes the value of 1. The parameter ρ and the parameter vector δ′ represent respectively the effects

of past IT capability superiority and firm characteristics, such as role of IT executives, on current ability to

achieve IT capability superiority. Eq. (2) models current firm performance (qit). The parameter γ and the

parameter vector β′ represent the effects of past firm's performance and firm characteristics on its current

performance respectively. Ceteris paribus, the impact of a senior IT executive's contribution on the firm's

competitive position is channeled through his/her success in helping the company develop superior IT

ϑqit

ϑqit ϑ ŷit

capability ϑCIO

= ϑy

. The dynamic binary choice model of stage one is estimated using the

ˆ it ϑCIOit−1

it−1

random-effect (RE) approach proposed by Wooldridge (2005). The second stage is estimated using OLS

with correction suggested by Murphy and Topel (2002). See Appendix B for a more detailed econometric

discussion of the estimation methodology.

The predicted value of IT capability (γ) in Eq. (2) will not have the desired properties, unless we account for

the fact that the residual in Eqs. (1) and (2) are correlated, Cov(uit, εit) ≠ 0 (Shaver 1998), and omitted

variables that affect both a firm's strategic choices and performance (Hamilton and Nickerson, 2003). To

account for the former, i.e., to allow for correlation between the processes governing the ability of the firm to

develop superior IT capability and the ensuing improved firm performance, we specify the two-stage model as

a system of two equations with correlated error terms Cov(uit, εit) ≠ 0. To account for the latter, fixed firm

effects are included in the specification to control for unobservable firm characteristics, which affect the firm's

strategic choices such as power of IT executive and IT capability. Firm specific fixed effects (ηi and αi

respectively) are proxied by firm dummies, and time effects (ϕt and ψt respectively) are proxied by year

dummies. Finally, to mitigate the possibility of endogeneity bias in the estimation of (1) due to the

contemporaneous inclusion of IT capability and firm-specific time-varying exogenous variables, we add the

time-varying exogenous variables (Sizeit − 1, ROAit − 1, and MVit − 1) with a one-period lag.

30

J.-H. Lim et al. / International Journal of Accounting Information Systems 13 (2012) 21–40

4. Empirical results

4.1. Descriptive statistics

During the sample time period 1997–2004 the majority of senior IT executives, 72% to 82%, were NonCIO. The average percentage of high power senior IT executives (CIO) was in the range of 18% to 28%. A

similar pattern was observed when we looked at the breakdown between CIO and Non-CIO within specific

industry sectors. On average, in the machinery, electronic, and other equipment industry the percentage of

CIO has been around 23%. In the service, transportation/utility, and financial industries the percentages

were 21%, 20%, and 19% respectively. In manufacturing the percentage of CIO was around 18%. Overall there

seems to be a gradual increase in the percentage of CIO.

Descriptive statistics (Panel A of Table 1) seem to indicate that the power of senior IT executives does

indeed matter for the firm's ability to achieve superior IT capability. More specifically, there is more than a

61% probability that firms with high power senior IT executives (CIO) this year will develop superior IT

capability next year. This result is about 40% higher than the probability that a firm with a less empowered

senior IT executive (Non-CIO) this year will develop superior IT capability next year.

Previous studies have shown that the probability that a firm will develop superior IT capability in the next year

is strongly dependent upon its current IT capability status (Lim et al., forthcoming). To account for this persistence

in IT capability superiority, we investigate the probability that the title of the senior IT executive in the current

year will affect the firm's ability to achieve superior IT capability in the following year. Concentrating on non-IT

capable firms and those that had a CIO leading their IT organization in the current year, the probability of these

firms developing superior IT capability in the following year is over 30% (untabulated results). The corresponding

probability for firms with Non-CIO was less than 10%. This is consistent with our prediction that the higher the

power of senior IT executives, the higher the likelihood that the firm will achieve superior IT capability.

Table 1

Descriptive statistics.

Panel A

Year t − 1 to t

Pr(IT Capabilityit|NonCIOit - 1)

1997–1998

1998–1999

1999–2000

2000–2001

2001–2002

2002–2003

2003–2004

Average

200/790

144/744

138/727

108/693

119/693

142/716

105/686

Pr(IT Capabilityit|CIOit - 1)

25.32%

19.35%

18.98%

15.58%

17.17%

19.83%

15.31%

18.79%

106/170

137/216

149/233

168/267

161/267

135/244

157/274

62.35%

63.43%

63.95%

62.92%

60.30%

55.33%

57.30%

60.80%

Panel B

IT capable firmst

Year t − 1 to t

1997–1998

1998–1999

1999–2000

2000–2001

2001–2002

2002–2003

2003–2004

Titlet − 1

CIOit - 1

NonCIOit - 1

CIOit - 1

NonCIOit - 1

CIOit - 1

NonCIOit - 1

CIOit - 1

NonCIOit - 1

CIOit - 1

NonCIOit - 1

CIOit - 1

NonCIOit - 1

CIOit - 1

NonCIOit - 1

Non-IT capable firmst

Tobin's q

Tobin's q

Tobin's q

Tobin's q

(Mean)t

(StD.)t

(Mean)t

(StD.)t

1.591

1.789

1.947

1.778

1.521

1 568

1.421

1.384

1.299

1.044

1.410

0.245

1.241

1.360

1.193

2.231

2.906

2.479

1.275

1.160

1.164

1.164

1.027

0.834

1.312

0.998

1.017

1.197

1.100

1.966

2.205

1.905

1.703

1.411

1.514

1.289

0.965

1.118

1.179

1.322

1.197

1.308

1.510

5.460

5.116

4.388

2.917

1.697

2.167

1.216

0.813

0.951

0.811

1.181

0.884

1.021

J.-H. Lim et al. / International Journal of Accounting Information Systems 13 (2012) 21–40

31

Table 1 — Panel B provides descriptive statistics for the three variables of interest: power of senior IT

executives, IT capability, and Tobin's q. Results are reported for two consecutive years at a time. For

example, the first set shows the mean and standard deviation of Tobin's q for the group of firms that had a

CIO in 1997 and had a superior IT capability in 1998 were 1.591 and 1.193 respectively. The average and

standard deviation of the Tobin's q for the group of firms that had a Non-CIO in 1997 and had no superior IT

capability (non-IT capability) in 1998 were 1.966 and 5.460 respectively.

Comparative results for the remaining years in the sample do not seem to indicate that the group of

firms with CIO in t − 1 and superior IT capability in year t are doing better than their competitors. This

casual observation is further supported by the untabulated results of ANOVA analysis. This lack of support

for the second hypothesis is expected and validates the aforementioned position that a chain effect must

be considered in order to observe the impact of the structural power of senior IT executives on their

firm's competitive position. Recall that the impact of IT executives on performance is captured in

ϑqit

ϑqit ϑˆyit

=

. While the table provides a similar interaction effect this is the simple product of

ϑCIOit−1

ϑ̂yit ϑCIOit−1

ϑqit

ϑqit

the two isolated effects

and

. In other words, descriptive statistics suffer from the same

ϑyit

ϑCIOit−1

weakness that was observed in the review of prior literature. Furthermore, these results do not control for

confounding factors known to affect Tobin's q, such as R&D intensity (R&D), advertising (AD), and capital

expenditures (CAP).

Table 2

Two-stage regression analysis (IT capable vs. Non-IT capable firms).

Unrestricted model

Restricted model

Coefficient (Std. error)

Coefficient (Std. error)

A. First-stage dynamic logit regression with Wooldridge-type correlated RE specification

yit − 1

0.309 (0.111)***

CIOit − 1

0.142 (0.052)***

SIZEit − 1

0.113 (0.052)**

ROAit − 1

0.044 (0.032)

MVit − 1

0.053 (0.044)

yi0

0.382 (0.132)***

CIOi;–1

0.098 (0.037)***

SIZEi;–1

0.072 (0.021)***

ROAi;–1

0.023 (0.015)*

MV i;–1

0.026 (0.015)*

Industry dummies

Included

Year dummies

Included

ση

0.457 (0.147)***

Ln L

− 1025.1

Wald1

0.117

Wald2

0.065**

Wald3

0.000***

#Obs.

6720

0.386 (0.126)***

0.115 (0.035)***

0.081 (0.027)***

0.025(0.015)*

0.031 (0.016)*

Included

Included

0.462 (0.141)***

− 1007.3

0.122

0.069**

0.000***

6720

B. Second-stage linear regression

qit − 1

R&Dit

ADit

CAPit

ŷit

Adjusted R2

#obs.

0.210

0.152

0.117

0.130

0.297

0.85

6720

0.208

0.152

0.116

0.129

0.294

0.85

6720

(0.077)**

(0.059)**

(0.049)**

(0.065)**

(0.102)***

0.312 (0.095)***

0.191 (0.073)***

0.127 (0.050)**

(0.078)**

(0.058)**

(0.049)**

(0.063)**

(0.103)***

Note. Wald1 records the p-value of the Wald test for the joint exclusion of ROAit − 1 and MVit − 1. Wald2 records the p-value of the Wald

test for the joint exclusion of year effects. Wald3 records the p-value of the Wald test for the joint exclusion of industry effects. The

term xi;−1 denotes the firm average of lagged x variables, such as the firm average of lagged values of the explanatory variables. The

standard errors of the OLS parameter estimates in the second stage are corrected for a generated regressor using an extended Murphy

and Topel (2002) estimator. ***, **, and * denote significance at the 1, 5, or 10% level, respectively.

32

J.-H. Lim et al. / International Journal of Accounting Information Systems 13 (2012) 21–40

4.2. Econometric results — IT executives, superior IT capability, and Tobin's q

Empirical results reported in Table 2 consist of two parts. Panel A shows the results of RE estimation as

a fully specified model. Panel B presents the results of the second stage linear regression. The RE

estimations of superior IT capability Eq. (1) are presented in the restricted and the unrestricted models.

Both models allow the IT capability to be dependent on lagged IT capability (yit − 1), the initial values of

IT capability status (yi0), firm-specific time-varying exogenous variables (CIOit − 1, Sizeit− 1, ROAit − 1, and

MVit − 1) and unobserved permanent firm heterogeneity (ση). The unrestricted model shows that one of

the time-varying exogenous covariates (Sizeit − 1) appears to be statistically significant. Based on the

insignificant results from the Wald test for joint exclusion of ROAit − 1 and MVit − 1, they were excluded

from the restricted version of the model. 6

Consistent with the first hypothesis (H1), the results of restricted RE estimates indicate that power of

senior IT executives is positively and statistically significantly associated with the firm's ability to achieve

IT capability superiority in the following year. The estimated parameter for CIO (δ1) is 0.191 it is

statistically significant (p-value < 1%). This indicates that the probability that a firm with a CIO will achieve

superior IT capability next year is approximately 19% higher than that of firm with a Non-CIO. In addition

to this, the parameter related to the path dependence of the IT capability (ρ) is 0.312 and highly significant

(p-value < 1%). This means that the probability that an IT capable firm will maintain its IT capability

superiority next year is 31.2% higher than that of a non-IT capable firm. 7 Lastly, there is some evidence

of time effects and very strong evidence of industry effects (Wald test in the restricted model; are

p-value = 0.069 and p-value = 0.000 respectively). 8

The results of the second stage linear regression strongly support the second hypothesis (H2). The

coefficient for the predicted IT capability status (γ) is 0.297 and it is statistically significant (p-value < 1%).

The other control variables are moderately significant and the explanatory power of the model is

relatively high (adjusted R 2 is 85%). As a robustness check we estimated Eq. (2) as a separate model and

it produced insignificant results (results have not been tabulated). Contrasting the robust evidence from

the second stage linear regression with the lack of evidence in descriptive statistics as well as from

the estimation of Eq. (2) as a separate model further validated our position. The impact of a senior IT

executive's contribution on the firm's competitive position is channeled through his/her success in

helping the company develop superior IT capability.

4.3. Econometric results – IT executives, enduring IT capability, and Tobin's q

The main premise of RBV and IT business value research is that only IT resources and capabilities that

are valuable and durably heterogeneous are rent yielding (Barney, 1991; Bhatt and Grover, 2005;

Ravichandran and Lertwongsatien, 2005). Durable heterogeneity of superior IT capability, in the context

of RBV, reflects a firm's ability to resist competitors' attempts to imitate or improve on its IT capability

(Barney, 1991). Several recent studies have shown that enduring superior IT capability is more value

adding than a non-enduring IT capability (Stratopoulos and Lim, 2010; Chen et al., forthcoming, and Lim

et al., forthcoming). As an additional validation for the hypotheses we consider the link between the

power of IT executives and a firm's ability to develop an enduring IT capability. Achieving and sustaining

such IT capability superiority will be possible for firms that can leverage feedback cycles of organizational

6

If the Wald test is significant, we can conclude that the parameters associated with the variables are not zero, so that the

variables should be included in the model.

7

According to Lim et al. (forthcoming) a positive and statistically significant estimate of ρ would identify the presence of

persistence in the firm's ability to achieve superior IT capability. That is, a firm that had superior IT capability in t − 1 is more likely

to achieve IT superiority in t. Therefore, achieving superior IT capability is a path dependent process. This has important strategic

implications, since path dependence means that competitors would find it difficult to acquire or develop similar capability.

According to RBV, if IT capability is path dependent then it is rent yielding.

8

Furthermore, as indicated by the highly significant estimates of ση (0.462), we note that unobserved permanent heterogeneity

accounts for a significant portion of the overall variance. Please note that a high level of unobserved permanent heterogeneity does

not imply a problem with model fit.

J.-H. Lim et al. / International Journal of Accounting Information Systems 13 (2012) 21–40

33

learning in a way that enables them to build stronger or reconfigured IT capabilities (Bhatt and Grover,

2005). Senior IT executives interacting with the firm's top management team are more likely to have the

business and IT knowledge needed to nurture such organizational learning. Therefore we expect that the

power of IT executives will be associated with a firm's ability to achieve enduring superior IT capability,

and firms with enduring IT capability will outperform firms with non-enduring IT capability.

Adopting the approach used in prior studies (Stratopoulos and Lim, 2010; Chen et al., forthcoming;

and Lim et al., forthcoming) we classify firms into three groups: Firms with enduring IT capability, nonenduring IT capability, and non-IT capable. This classification is based on the cross-sectional evolution of a

firm's recognition in IW500 over four-year rolling windows (i.e., 1997–00, 1998–01, 1999–02, 2000–03,

and 2001–04). For each window we classify a firm as a having an enduring IT capability if it has been

recognized in IW500 all years within a four-year rolling window. A firm is classified as having a nonenduring IT capability if it has appeared less than four times in a four-year rolling window. Non-IT capable

firms are those that have not been recognized in any of the 4 years.

The two-stage regression analysis of firms with enduring IT capability versus firms with nonenduring IT capability is reported in Table 3 and clearly validates the position of this study. Results

show that the probability that a firm with a high ranking senior IT executive (CIOit − 1) will achieve an

enduring IT capability superiority is 17% higher than that of a firm with a Non-CIOit − 1. Additionally, the

contribution of IT executives on Tobin's q through superior and enduring IT capability is statistically

Table 3

Two-stage regression analysis (firms with enduring vs. non-enduring IT capability).

Unrestricted model

Restricted model

Coefficient (Std. error)

Coefficient (Std. error)

A. First-stage dynamic logit regression with Wooldridge-type correlated RE specification

yit − 1

0.382 (0.121)***

CIOit − 1

0.166 (0.057)***

SIZEit − 1

0.125 (0.055)**

ROAit − 1

0.071 (0.049)

MVit − 1

0.082 (0.050)

yi0

0.414 (0.155)***

CIOi;–1

0.103 (0.039)***

SIZEi;–1

0.077 (0.029)***

ROAi;–1

0.038 (0.016)**

MV i;–1

0.029 (0.012)**

Industry dummies

Included

Year dummies

Included

ση

0.379 (0.117)***

Ln L

− 998.1

Wald1

0.123

Wald2

0.055**

Wald3

0.000***

#Obs.

474

0.415 (0.153)***

0.106 (0.040)***

0.079 (0.30)***

0.041 (0.017)**

0.035 (0.015)**

Included

Included

0.383 (0.119)***

− 1001.3

0.129

0.063**

0.000***

474

B. Second-stage linear regression

qit − 1

R&Dit

ADit

CAPit

^

yit

Adjusted R2

#obs.

0.228

0.197

0.104

0.110

0.355

0.82

474

0.226

0.194

0.103

0.111

0.353

0.82

474

(0.076)***

(0.079)**

(0.040)**

(0.046)**

(0.104)***

0.390 (0.119)***

0.171 (0.056)***

0.132 (0.052)**

(0.075)***

(0.080)**

(0.040)**

(0.048)**

(0.105)***

Note. Wald1 records the p-value of the Wald test for the joint exclusion of ROAit − 1 and MVit − 1. Wald2 records the p-value of the Wald

test for the joint exclusion of year effects. Wald3 records the p-value of the Wald test for the joint exclusion of industry effects. The

term xi;−1 denotes the firm average of lagged x variables, such as the firm average of lagged values of the explanatory variables. The

standard errors of the OLS parameter estimates in the second stage are corrected for a generated regressor using an extended Murphy

and Topel (2002) estimator. ***, **, and * denote significance at the 1, 5, or 10% level, respectively.

34

J.-H. Lim et al. / International Journal of Accounting Information Systems 13 (2012) 21–40

significant. That is, the coefficient for the predicted superior and enduring IT capability status (γ) is 0.355

(p-value < 1%).

Perhaps an even stronger validation to the importance of using a chain effect approach for measuring

the impact of IT executives on firm performance comes from the comparison of firms with non-enduring

IT capability and non-IT capable firms on Table 4. Recall that according to prior evidence (Stratopoulos

and Lim, 2010; Lim et al., forthcoming) a non-enduring IT capability superiority is not a source of

competitive advantage. Therefore, a senior IT executive who delivers a non-enduring IT capability is not

making a value adding contribution to his/her company. Consistent with this, the results show that while

the power of senior IT executives has a moderate effect on a firm's ability to achieve non-enduring IT

capability, the effect of non-enduring IT capability on firm performance is not statistically significant. The

probability that a firm with a CIOit − 1 will achieve a non-enduring IT capability superiority is 9% higher

than that of firm with a Non-CIOit − 1. The coefficient for the predicted non-enduring IT capability status

(γ) is 0.068 and it is not statistically significant.

4.4. Additional tests

As robustness check we estimate an endogenous self-selection model with fixed effects by using

an extension to Heckman's (1979) correction to control for the self-selection bias. The predicted values from

Table 4

Two-stage regression analysis (firms with non-enduring vs. non-it capability).

Unrestricted model

Restricted model

Coefficient (Std. error)

Coefficient (Std. error)

A. First-stage dynamic logit regression with Wooldridge-type correlated RE specification

yit − 1

0.226 (0.114)**

CIOit − 1

0.087 (0.044)**

SIZEit − 1

0.101 (0.054)*

ROAit − 1

0.028 (0.017)

MVit − 1

0.037 (0.023)

yi0

0.314 (0.134)**

CIOi;–1

0.051 (0.024)**

SIZEi;–1

0.048 (0.024)**

ROAi;–1

0.015 (0.008)*

MV i;–1

0.020 (0.012)*

Industry Dummies

Included

Year Dummies

Included

ση

0.623 (0.229)***

Ln L

− 1184.7

Wald1

0.106

Wald2

0.058**

Wald3

0.000***

#Obs.

1640

0.322 (0.138)**

0.063 (0.027)**

0.054 (0.026)**

0.016 (0.008)*

0.022 (0.013)*

Included

Included

0.625 (0.228)***

− 1179.2

0.113

0.061**

0.000***

1640

B. Second-stage linear regression

qit − 1

R&Dit

ADit

CAPit

ŷit

Adjusted R2

#obs.

0.141

0.092

0.155

0.208

0.068

0.62

1640

0.139

0.088

0.152

0.215

0.077

0.61

1640

(0.072)*

(0.042)**

(0.092)

(0.107)*

(0.047)

0.231 (0.117)**

0.090 (0.046)**

0.113 (0.062)*

(0.074)*

(0.046)**

(0.095)

(0.109)*

(0.041)

Note. Wald1 records the p-value of the Wald test for the joint exclusion of ROAit − 1 and MVit − 1. Wald2 records the p-value of the Wald

test for the joint exclusion of year effects. Wald3 records the p-value of the Wald test for the joint exclusion of industry effects. The

term xi; −1 denotes the firm average of lagged x variables, such as the firm average of lagged values of the explanatory variables. The

standard errors of the OLS parameter estimates in the second stage are corrected for a generated regressor using an extended Murphy

and Topel (2002) estimator. ***, **, and * denote significance at the 1, 5, or 10% level, respectively.

J.-H. Lim et al. / International Journal of Accounting Information Systems 13 (2012) 21–40

35

Table 5

Results for Endogenous Self Selections model with fixed effects using Heckman's (1979) extension.

B. Second-stage linear regression

Panel A: IT capable vs. non-IT capable firms

qit − 1

R&Dit

ADit

CAPit

λ̂it

Adjusted R2

#obs.

Panel B: firms with enduring vs. non-enduring

qit − 1

R&Dit

ADit

CAPit

λ̂it

Adjusted R2

#obs.

Unrestricted model

Restricted model

Coefficient (Std. error)

Coefficient (Std. error)

0.201

0.147

0.108

0.114

0.263

0.88

6720

0.213

0.152

0.117

0.130

0.297

0.90

6720

(0.107)**

(0.065)**

(0.059)**

(0.060)**

(0.137)**

0.215

0.181

0.098

0.103

0.318

0.88

474

(0.102)**

(0.090)**

(0.44)**

(0.051)**

(0.144)**

0.131

0.083

0.149

0.202

0.047

0.66

1640

(0.072)*

(0.042)**

(0.091)

(0.120)*

(0.029)

(0.101)**

(0.066)**

(0.049)**

(0.058)**

(0.132)**

IT capability

0.213 (0.103)**

0.176 (0.088)**

0.095 (0.043)**

0.098 (0.049)**

0.311(0.132)**

0.86

474

Panel C: firms with non-enduring vs. non-IT capability

qit − 1

0.122 (0.073)*

R&Dit

0.071 (0.042)*

ADit

0.144 (0.096)

CAPit

0.209 (0.124)*

λ̂it

0.056 (0.035)

Adjusted R2

0.64

#obs.

1640

Note: the standard errors of the OLS parameter estimates in the second stage are corrected for a generated regressor using an

extended Murphy and Topel (2002) estimator. ***, **, and * denote significance at the 1, 5, or 10% level, respectively.

this first-stage regression ( ŷit ) are used to compute the inverse of Mill's ratio (IMR) as follows:

λ ŷit = f ŷit = F ŷit , if yit = 1 and −λ ŷit = −f −ŷit = F −ŷit , if yit = 0, where f ŷit and F ŷit represent

the probability density function and cumulative density function, respectively. Including the IMR in the

second-stage regression provides a control for potential selectivity bias in our examination of the effects

of firm's choices regarding IT executives and IT capability in Eq. (2′).

qit = μqit−1 + β1 R&Dit + β2 ADit + β3 CAPit + η λ̂it + αi + ψt + εit

ð2′Þ

where λ̂it = λ ŷit is the IMR. The sign of the estimate of η in Eq. (2′) is determined by the sign of the

correlation between the error terms in Eq. (1) and qit = μqit − 1 + β1R & Dit + β2ADit + β3CAPit + αi + ψt + εit.

Results of the endogenous self-selection model with fixed effects using Heckman's (1979) extension are

reported in Table 5. As expected, the estimated coefficients of λ̂it are positive. These results suggest a

positive correlation between the processes governing firm's choice regarding power of IT executives, firm's

ability to develop superior IT capability, and the resulting improvement in firm performance. For example,

Table 5 Panel A reports results for the second stage regression analysis based on IT capable vs. non-IT

capable firms. The coefficient estimates of λ̂it in the unrestricted and restricted models are respectively

0.263 and 0.297 with t-statistics of 1.99 and 2.17 in absolute values. The estimated coefficients are

statistically significant at the 5% level. 9

This study uses Tobin's Q as a proxy for firm performance because it is likely to capture such

intangibles as good management skills and superior IT capability. As a robustness check we run the

analysis using ROA as the performance measure in the second stage. The results reported in Table 6 are

9

For a more general discussion on endogeneity and self-selection and how they relate to this study see Appendix C.

36

J.-H. Lim et al. / International Journal of Accounting Information Systems 13 (2012) 21–40

Table 6

Two stage regression analysis with ROA as dependent variable in second stage.

B. Second-stage linear regression with ROA as the dependent variable

Panel A: IT capable vs. non-IT capable firms

ROAit − 1

R&Dit

ADit

CAPit

ŷit

Adjusted R2

#obs.

Note: first stage results are same as in Table

Unrestricted model

Restricted model

Coefficient (Std. error)

Coefficient (Std. error)

0.165 (0.086)*

0.089 (0.038)**

0.075 (0.042)*

0.107 (0.059)*

0.211 (0.095)**

0.74

6720

2 — Panel A.

0.182

0.102

0.093

0.114

0.228

0.77

6720

(0.094)*

(0.042)**

(0.047)**

(0.063)*

(0.090)**

Panel B: firms with enduring vs. non-enduring IT capability

ROAit − 1

0.186 (0.109)*

R&Dit

0.173(0.098)*

ADit

0.086 (0.041)**

CAPit

0.092 (0.048)*

ŷit

0.269 (0.118)**

Adjusted R2

0.71

#obs.

474

Note: first stage results are same as in Table 3 — Panel A.

0.193

0.181

0.095

0.107

0.270

0.75

474

(0.097)**

(0.096)*

(0.043)**

(0.058)*

(0.113)**

Panel C: firms with non-enduring vs. non-IT capability

ROAit − 1

0.087 (0.052)*

R&Dit

0.039 (0.024)

ADit

0.116 (0.069)*

CAPit

0.185 (0.114)

ŷit

0.039 (0.024)

2

Adjusted R

0.46

#obs.

1640

Note: first stage results are same as in Table 2 — Panel A.

0.083

0.057

0.124

0.192

0.051

0.49

1640

(0.042)**

(0.034)*

(0.066)*

(0.115)*

(0.031)

Note: the standard errors of the OLS parameter estimates in the second stage (Table 6 Panels A to C) are corrected for a generated

regressor using an extended Murphy and Topel (2002) estimator. ***, **, and * denote significance at the 1, 5, or 10% level, respectively.

slightly weaker but consistent with the position of this study. The relative weakness is due to the fact

that ROA is much noisier measurement compared to Tobin's q. Results based on contrasting of IT

capable and non-IT capable firms (Table 6 Panel A) show that the contribution of IT executives on ROA

through superior IT capability is statistically significant. That is, the coefficient for the predicted IT

capability status (γ) is 0.228 (p-value < 5%). Similarly, results based on the contrast of firms with

superior and enduring IT capability versus firms with superior but non-enduring IT capability (Table 6

Panel B) show that the coefficient for the predicted superior and enduring IT capability status is 0.277

(p-value < 5%). Finally, results based on the contrast of firms with non-enduring IT capability versus

firms non-IT capability (Table 6 Panel C) show that the effect of non-enduring IT capability on ROA is

not statistically significant.

5. Discussion and conclusion

Evaluating the business value of IT remains one of the most interesting questions for researchers and

professionals. This interest is motivated by the realization that ability to extract value from investment in

IT resources and capabilities, while feasible, is far from certain. In this study we propose coupling the role

of IT executives with IT capability in order to evaluate their effect on firm performance. More specifically

we theorize and find empirical evidence to support the following positions: first, there is a positive

relationship between the hierarchical power of senior IT executives and the likelihood that the firm will

develop superior IT capability. Second, the contribution of IT capability to a firm's competitive advantage

J.-H. Lim et al. / International Journal of Accounting Information Systems 13 (2012) 21–40

37

is much stronger in firms with powerful senior IT executives as they are the driving force that may ensure

the continuous renewal of IT capability.

This study makes several contributions to IT business value literature. First, it suggests the need to

extend the prior literature on IT capability and firm performance with a search for factors that have a

multiplicative effect on the payoffs from IT capabilities. Second, existing literature is leveraged to theorize

and empirically validate the proposition that the power of senior IT executives works multiplicatively

with IT capability. Third, a relatively new area of research is illuminated, such as the value adding

contribution of incumbent senior IT executives. Fourth, the study demonstrates that senior IT executives

who leverage their power to develop a superior and enduring IT capability are making a much stronger

contribution to their company than IT executives who develop a superior but non-enduring IT capability.

Finally, identifying antecedents of IT capability, i.e., factors that lead a firm to achieve and sustain superior

IT capability, as well as recognizing the role that these factors play on the rent yielding capacity of IT

capability helps to illuminate the proverbial black box of IT business value research.

Naturally, like similar studies, there are limitations that must be acknowledged. First, since

InformationWeek has been a well-respected and widely used source of secondary information on IT capability

(Bharadwaj, 2000; Santhanam and Hartono, 2003), it was assumed that firms listed in IW500 are a proxy for

firms with superior IT capability. However, we cannot confirm that the IW500 firms are independently

evaluated each year. Second, Finkelstein (1992) suggests that official title, number of titles, and compensation

are a proxy of hierarchical power. While we use official title and number of titles, compensation was excluded

because only 8% of IT managers' compensation data is publicly available. Nevertheless, since the empirical

results are consistent with the anecdotal evidence offered by the IT leaders such as PNC, Intel, Harrah's

Entertainment and many others, these limitations do not seem to compromise the main message of our study.

Future research could attempt to resolve some of these limitations or extend our research by considering

other characteristics of senior IT executives such as experience, education, connection to other business and IT

executives and how they affect their ability to add value to their firm through IT capability. Finally, as

mentioned in the introduction this study has important practical implications for senior business executives

who want to compete through IT enabled strategies. We suggested that bestowing more power on senior IT

executives increases the likelihood that the firm will develop and sustain superior IT capability, the sine qua

non for an IT enabled strategy. Related to this observation, future research could evaluate the extent to which

firms reciprocate by rewarding the contribution of senior IT executives to their firm's ability to achieve and

sustain superior organizational IT capability.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Andreas Nicolaou (Editor) and the three anonymous referees for their

careful reviews and constructive suggestions. We also thank the anonymous reviewers and participants at

the 2011 International Conference on Enterprise Systems, Accounting and Logistics. The authors

acknowledge the financial support provided by the Social Sciences Humanities Research Council of

Canada (SSHRC) and the University of Waterloo.

Appendix A. Variable descriptions

Variables

Definition

yit

qit

DV-stage 1

DV-stage 2

CIOit

SIZEit

ROAit

MVit

R & Dit

CAPit

ADit

IV

CV

CV

CV

CV

CV

CV

1 for firms with superior IT capability in t, otherwise 0.

Tobin's q: a ratio of market value [(fiscal year-end market value of equity) + (liquidating value of the

firms' outstanding preferred stock) + (current liabilities) − (current assets) + (book value of

inventories) + (long-term debt)] to book value of total assets.

1 if a senior IT executive has the formal title of CIO or CIO with additional official titles, otherwise 0.

Natural logarithm of total assets.

Return on assets in year t − 1.

Market-to-book-value.

Research and development expenditure/net sales.

Capital expenditure/net sales.

Advertising expense/net sales.

38

J.-H. Lim et al. / International Journal of Accounting Information Systems 13 (2012) 21–40

Appendix B. Estimation methodology

In Eq. (2), ŷit is the predicted value of the first-stage regression. Instead of using a full-information

maximum likelihood, which would be extremely intricate in our case, we adopt a two-step procedure in

which the first-stage regression is estimated by using the random-effect (RE) approach proposed by