Ingratiation and Favoritism

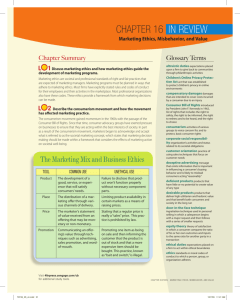

advertisement